“Dodgy prawns,” insists the narrator in Replay, the affecting solo show written and performed by Nicola Wren, were the cause of her violent physical reaction upon hearing of a man’s suicide. It wasn’t pregnancy or anything else. The narrator, a woman police officer (identified only as W in the program), assures the audience that she is made of sterner stuff than to be shaken by the emotional impact of meeting the wife and daughter of the man, who took his life earlier that day. Dodgy prawns: This is her story, and she is sticking with it. As W describes in painful detail the personal turmoil surrounding her visit to the London home, one begins to suspect the prawns may be receiving a bum rap.

King Lear

In 1940 British critic James Agate said of John Gielgud’s King Lear: “I do not feel that this Lear’s rages go beyond extreme petulance—they do not frighten me!” No such reservation afflicts Gregory Doran’s intelligent and well-spoken Royal Shakespeare Company production, which stars Antony Sher as the king—the Shakespearean role that Sher, who last year played Falstaff at BAM, says will be his last.

This Flat Earth

Lindsey Ferrentino’s This Flat Earth joins other recent plays in tackling a hot-button issue: Admissions at Lincoln Center examined affirmative action, and Miss You Like Hell at the Public is entwined with the deportation of illegal aliens, or undocumented immigrants, depending on one’s political leaning. Ferrentino’s chosen subject is gun violence in schools.

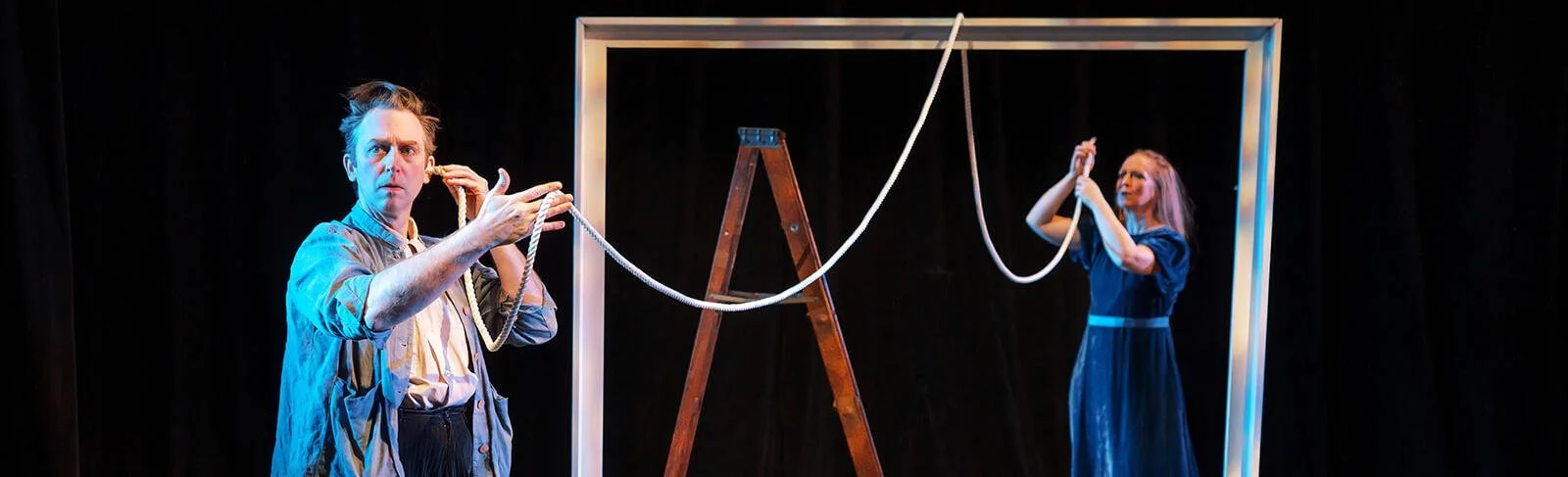

Happy Birthday, Wanda June

The reputation of Kurt Vonnegut nowadays rest on his comic novels—a mainstay of 1960s counterculture. He combined flights of hilarious whimsy with science fiction and sharp satire in works such as Cat’s Cradle (1963), God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater (1965) and Slaughterhouse-Five (1969). But at the height of his powers, Vonnegut also wrote a Broadway play, Happy Birthday, Wanda June. The play may not be a masterpiece, but the production by the Wheelhouse Theater Company under director Jeff Wise breathes screwball life into it with strong performances and unabashed theatricality.

The Edge of Our Bodies

A 16-year-old prep school student takes a train to New York City, spends some time in a bar, encounters odd sexual shenanigans in a hotel room, and struggles with an assortment of inner conflicts. In 1951, J. D. Salinger turned this scenario into gold with The Catcher in the Rye. But, in the TUTA Theater Company’s abstract and lumbering production of a 2011 play by Adam Rapp, these same elements hold little value. With extensive doses of narration broken only by a few unexplainable affronts of noise and light, The Edge of Our Bodies shares a border with the limits of our patience.

No One Writes to the Colonel

In 1956, New York Times critic Brooks Atkinson described a new play by Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot, as “a mystery wrapped in an enigma.” That Churchillian phrase captures the Godot-like inscrutability of No One Writes to the Colonel (El coronel no tien quien le escriba), an early novella by Nobel laureate Gabriel Gárcia Márquez (1927–2014).

Leisure, Labor, Lust

Sara Farrington’s Leisure, Labor, Lust has interesting subject matter—the intersection of class divisions and sexual orientation in the early 20th century—that is rarely explored in American theater. As a subject, the intertwining of sexual desire across class lines underlay The Judas Kiss, David Hare’s 1998 play about Oscar Wilde, but unfortunately Farrington brings little new to the table except the persons on whom she has modeled her characters.

The Stone Witch

The ups and downs of the creative process are personified as “beasts which must be tamed” in The Stone Witch, a new play by Shem Bitterman. The work is a somewhat convoluted and ultimately contrived attempt to tackle the psychological complexities of creating art. And while Steve Zuckerman’s production is visually and aurally rich, the whole is not greater than the sum of its parts.

The Winter’s Tale

It’s a truism that William Shakespeare’s tragicomedy The Winter’s Tale divides into two distinct parts. In the first, Leontes, king of Sicilia, suspects his queen, Hermione, of adultery with his friend Polixenes, king of Bohemia, who has been spending a long sojourn with them but who is leaving for his home country immediately. The biggest hurdle for actors playing Leontes is to make his sudden jealousy credible. “The part is one of the hardest ever written,” Margaret Webster noted in Shakespeare Without Tears: “with almost no preparation, the emotion of it is at flood height.”

A Walk in the Woods

When Lee Blessing’s A Walk in the Woods opened in 1988 at the Lucille Lortel Theater and then moved to Broadway, Ronald Reagan was President and the Soviet Union had not yet collapsed. Blessing’s two-character play about a Russian and an American diplomat discussing arms reduction in a series of meetings in Geneva was fresh and timely—and splendidly acted by Sam Waterston and Robert Prosky.

Babette’s Feast

Babette’s Feast, based on a short story by Danish writer Isak Dinesen, centers not on the namesake of the title, but instead on two sisters: Philippa (Juliana Francis Kelly) and Martine (Abigail Killeen, who conceived and developed the show), the daughters of a rector (Sturgis Warner) who heads an ascetic Protestant sect. In Berlevåg, a small town on the coast, their lives are is pretty ho-hum, except for a few spats between congregants, until Babette (the earthy and grounded Michelle Hurst) arrives. She is an exile who has escaped the Paris Commune of 1870, an uprising she took part in, and has made her way to where the sisters live, on the recommendation of an opera singer who once, long ago, passed through the town.

Dido of Idaho

Abby Rosebrock is a different kind of triple threat. As a playwright, she brings an invigorating new voice to the stage with the debut of her comedy-drama Dido of Idaho, at the Ensemble Studio Theatre. As an actor in her own play, portraying a former beauty pageant contestant in crisis, her comic timing is precise. And as a practitioner of stage combat, “threat” is too gentle a word for her character who, when faced with a challenge to her domestic security, brandishes a razor-sharp pair of cuticle scissors.

Three Small Irish Masterpieces

The triple bill of one-acts at the Irish Repertory Theatre is a rare chance to see plays by Lady Gregory, William Butler Yeats and John Millington Synge, although in small-space productions downstairs at the invaluable venue. One may not feel that the first two plays, The Pot of Broth and The Rising of the Moon, should occupy the umbrella title of Three Small Irish Masterpieces alongside Synge’s Riders to the Sea, which fits the bill; the first two seem slight by comparison. But they make a pleasant enough evening of unfamiliar entertainment, enhanced by the proximity to St. Patrick’s Day.

Hal & Bee

As inspirations go, the combination of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and The Secret Life of Walter Mitty is certainly an odd one, yet those sources are echoed in Max Baker’s charming, offbeat comedy Hal & Bee.

Is God Is

The Soho Rep had been staging vital productions out of its small Walker Street theater in Tribeca for a quarter century when it was discovered, in 2016, that the company had been in violation of an occupancy limit of 70 people. Through a combination of fund-raising and city agency support, the company has now returned to its home space, which includes a new fire-safety system. It is a fitting improvement, because flames are the essential metaphor of Aleshea Harris’s explosive Is God Is. In this allegorical tale of vengeance and family honor, twin sisters, burned both literally and figuratively, create an inferno that swallows nearly everyone they meet.

Terminus

How deep can one hide the truth? Gabriel Jason Dean’s Terminus centers on the search for the “true true”—a phrase spoken by a few of the characters. It captures the essence of this well-written, thought-provoking play, the second in a seven-play cycle called The Attapulgus Elegies. The collection chronicles the lives of the residents of Attapulgus, Ga., over the course of the last two decades as the town slowly dwindles away.

Fusiform Gyrus

An avant-garde, two-man show with five horn players, Fusiform Gyrus is like sliding down a long chute. It’s a reckless and even fun adventure, but you’re totally unsure of where you’ll end up. Written by Obie Award–winning Ellen Maddow and directed by Ellie Heyman at HERE Arts Center, Fusiform Gyrus is a meditation on life, death, and everything in between.

In the Body of the World

The Manhattan Theatre Club stage at City Center is giving off major Disney World Jungle Cruise vibes these days. Birds call over the syncopated groove of Nigerian percussionist Solomon Ilori’s 1963 deep cut “Tolani (African Love Song)” as patrons enter the theater. There’s a Tara Buddha statue downstage right, some Persian rugs, a scarlet chaise lounge and some cushions on the floor, and the proto-Afrobeat music morphs into the Middle Eastern goblet drums and chirpy marimba that have been cornerstones of “world music” for decades. It’s almost disappointing when no chipper, punning Adventureland employee pulls up to take you downriver.

Returning to Reims

The Schaubühne Berlin production of Returning to Reims addresses fascinating material—the evolution of French political life in the 20th century, notably a working class that was heavily communist in the 1920s to one that increasingly embraces the right-wing National Front of Marine Le Pen. U.S. dramatists rarely tackle political subjects of such depth, but the static execution of Thomas Ostermaier’s production undercuts much of the daring of that choice.

Cardinal

Signs of the decline and fall of the American Empire are everywhere visible, but perhaps nowhere more than in the Rust Belt, which has decay and depression hammered right into its nickname. Detroit may be its most potent symbol, but this ribbon, stretching from New York to Wisconsin, is peppered with towns both large and small that have never quite recovered from the trauma of deindustrialization.