Staged in independent bookstores across New York City, playwright-actor-director Ed Schmidt serves as narrator in his solo play, Edward, using twenty-seven mundane artifacts to reconstruct the memory of Edward O’Connell, a former high school English teacher.

In Edward, written, performed, and directed by Ed Schmidt, a small box of 27 mundane artifacts becomes a form of domestic archaeology, each item revealing a fragment of a life once lived. Gathered around a table in independent bookstores across New York City, audiences help reconstruct—night by night—a portrait of the late Edward O’Connell, a former high school English teacher whose faith in literature echoes through the stories and the spaces where they are told.

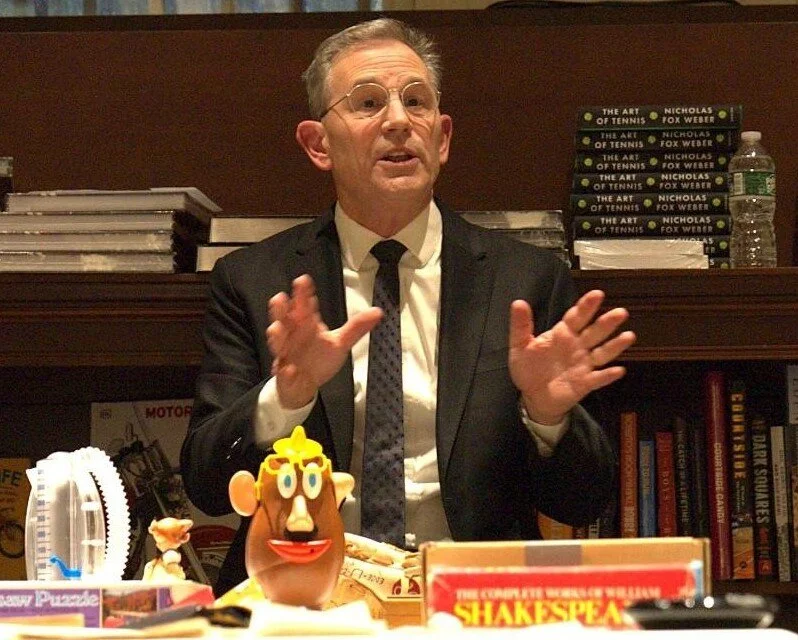

Schmidt holds an “E” flag, affectionately impersonating the secretary of the headmaster who retired the same year he did from Enright Academy. Photographs by Emma Callahan.

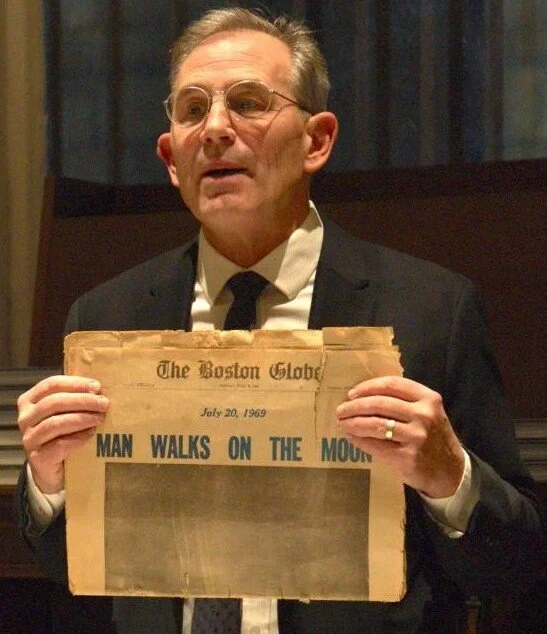

Audience members (maximum 25 per performance) are invited to arrive early and examine the artifacts, laid out on a long, rectangular table. At the head sits a cardboard box stamped “fragile,” an arrow pointing upward—a quiet instruction in reverence, encouraging guests to handle the objects as if they were relics and to linger over their private, almost sacred, meanings. Among the items are the front page of The Boston Globe, its headline declaring “Man Walks on the Moon” on July 20, 1969; a curling photograph of a young girl in a plaid shirt with ragged bangs; and a simple pocketknife.

Schmidt understands the value of forging a bond between audience and object. Early arrivals mill around the table, inspecting a program for Arthur Miller’s All My Sons, a traveling chess set, a spirometer, and other items—momentarily transported to another time and place before a word is spoken.

Once everyone is seated in the elegant salon at the back of the Rizzoli Bookstore—the 64-year-old Schmidt materializes almost out of thin air. Dressed formally, he appears Old World and quietly erudite, without pretension. Schmidt begins with an introduction to Edward, distilling for the audience the essential facts of its eponymous protagonist:

Edward O’Connell died 12 years ago, at the age of 73, and left behind this box and all that it contained. With these 27 objects, are over ten octillion ways to tell Edward’s story—an unfathomable number. Tonight, we will tell one of those versions. Where shall we begin?

Schmidt gestures to an audience member to select the first object. The Bible is chosen, and Schmidt lifts it carefully from the table, cradling it in his hand to keep its precariously loose front cover and worn spine from giving way. Schmidt explains that Edward’s grandfather received the Bible on his wedding day in 1894 and carried it with him across the sea from Ireland to America, where it held pride of place on the family’s living-room end table. Passed down from grandfather to father and then to Edward himself on his wedding day in 1961, the Bible charts a lineage of belief that eventually falters: though Edward and his Protestant bride, Angela, were married in a Catholic church, Edward would later drift away from his faith, and the Bible would wind up “on the back of a shelf in a clothes closet.” Surrounded on three sides by the audience, Schmidt holds the room in silence before gently placing the Bible into the cardboard box and motioning to another guest to choose what comes next.

Schmidt’s storytelling quietly subverts conventional theatrical form in his experimental audience-guided play.

Schmidt’s storytelling quietly subverts conventional theatrical form. Edward is an audience-guided work, one in which Schmidt relinquishes control of the narrative’s rudder, allowing viewers to determine the order of the objects—and, by extension, the sequence in which Edward’s life is revealed, in all its shallows and depths. During the 95-minute performance, Schmidt’s voice shifts through amiability, wistfulness, longing, anger, and acceptance.

Schmidt has long favored intimate solo performance. The Last Supper (2003), a meditation on the final meal Jesus shared with his apostles as seen through the eyes of the women who prepared it, unfolded in Schmidt’s Brooklyn home for an audience of 12 guests, complete with a shared meal. My Last Play (2010) was framed as a personal farewell to theater, inviting 12 audience members into his home to witness a turning point in his life and leave with a book from his personal library. He first gained wider notice with the ensemble play Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting (1989), which dramatizes a pivotal conversation surrounding Jackie Robinson.

What ultimately distinguishes Edward is not its ritualized tenderness but its clear-eyed understanding of how memory actually works—selective, contradictory, shaped as much by omission as by preservation. By allowing the audience to guide the narrative, Schmidt resists the temptation to sanctify Edward’s life, instead revealing a man defined by accumulation rather than destiny, by objects that gather meaning over time and then quietly lose it. The result is a work that feels less like an elegy than an act of shared witnessing: intimate, humane, and gently unsentimental in its recognition that a life, however carefully remembered, can only ever be partially told.

Edward plays through March 1 at various independent bookstores in Brooklyn, Queens, and Manhattan. Performance dates and times are irregular and may be viewed, along with additional information, at edschmidttheater.com.

Playwright & Director: Ed Schmidt