Two-character plays are a tricky thing to pull off. When they are successful, they can be engaging entertainments. Sleuth boasted a great deal of mind games, along with costume changes. In the past season, The Roommate and Dakar 2000 traveled through scene and time changes, but with expectations often upended. Although Philip Stokes’s Shellshocked also relies on mind games, it feels hermetically sealed.

Gertrude Lawrence: A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening

If the British actress Gertrude Lawrence is remembered at all nowadays, it is primarily for originating the part of Anna Leonowens in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s The King and I (1951). She didn’t get the role in the 1956 film, and her reputation rests on a long theatrical career in Britain and America, as Lucy Stevens’s gossipy Gertrude Lawrence: A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening, makes clear.

The Last Laugh

Three of Britain’s leading comedians of the 20th century are the focus of Paul Hendy’s The Last Laugh, a play that harks back to Sutton Vane’s Outward Bound (1923) and Trevor Griffiths’ Comedians (1975). As the trio meets in a shabby dressing area of an uncertain venue for some kind of benefit performance, issues of what makes something funny and who steals jokes from whom, along with plenty of comic insults, arise.

Invisible

Nikhil Parmar’s relentlessly kinetic solo show Invisible is an impressive hourlong workout for the actor. The words tumble out, the situations are plentiful, and he breaks the fourth wall time and again. If he had not written the piece for himself, one might regard the movement as a mistake by a novice, but Parmar intends to show what he can do, vocally and physically, and with a vengeance.

Handbagged

It’s just a side benefit to an already crackling evening, but if you see Handbagged, the latest in 59E59’s Brits Off Broadway series, you’ll also take in snippets from several current Broadway offerings. The 1981 Irish hunger strikes (The Ferryman)? They’re here. Rupert Murdoch’s takeover of several Brit tabloids, beginning with the Sun in the late ’60s (Ink)? Also here. And The Cher Show may present three different-aged Chers, each commenting on the others, but Handbagged, Moira Buffini’s 2010 play having its New York premiere, makes do with older and younger versions of Queen Elizabeth II and Margaret Thatcher, each interacting with the past and present and occasionally murmuring, “I didn’t say that.”

Posting Letters to the Moon

Posting Letters to The Moon brings a heartfelt performance to the Brits Off Broadway festival at 59E59 Theaters. Compiled by Lucy Fleming, the daughter of British actress Celia Johnson and an actress herself, Posting Letters to The Moon is a reading of letters between her parents during World War II. Johnson, best known for the 1945 David Lean film Brief Encounter, for which she was nominated for an Oscar, was married to Peter Fleming, an accomplished writer and explorer; he was also the brother of Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond. Lucy Fleming and her husband, Simon Williams, an actor best known as Mr. Bellamy in Upstairs, Downstairs, read the parts of her parents.

Caroline’s Kitchen

A British celebrity cook’s life isn’t so camera-perfect in Torben Betts’s Caroline’s Kitchen, a U.K. transplant now playing in 59E59 Theaters’ Brits Off-Broadway festival. The high-tension new play centers on BBC cooking host Caroline (Caroline Langrishe), the “darling of Middle England,” whose privileged life goes up in flames over the course of an evening—along with the roast.

All I Want Is One Night

Time has not been kind to Suzy Solidor, the Parisian nightclub sensation of the 1930s. Solidor earned a reputation as “the most-painted woman in the world,” and her image was captured by some of the greatest artists of the 20th century, including Tamara de Lempicka, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, and dozens of others. Known primarily for her erotic songs about lesbian desire, Solidor is all but forgotten today, but the immensely gifted singer and actress Jessica Walker may just rescue her from the footnotes of entertainment history. Walker’s new work, All I Want Is One Night, which is part of the Brits Off Broadway series at 59E59 Theaters, offers compelling reason to become reacquainted (or, as the case may be, acquainted) with the cross-dressing French cabaret singer.

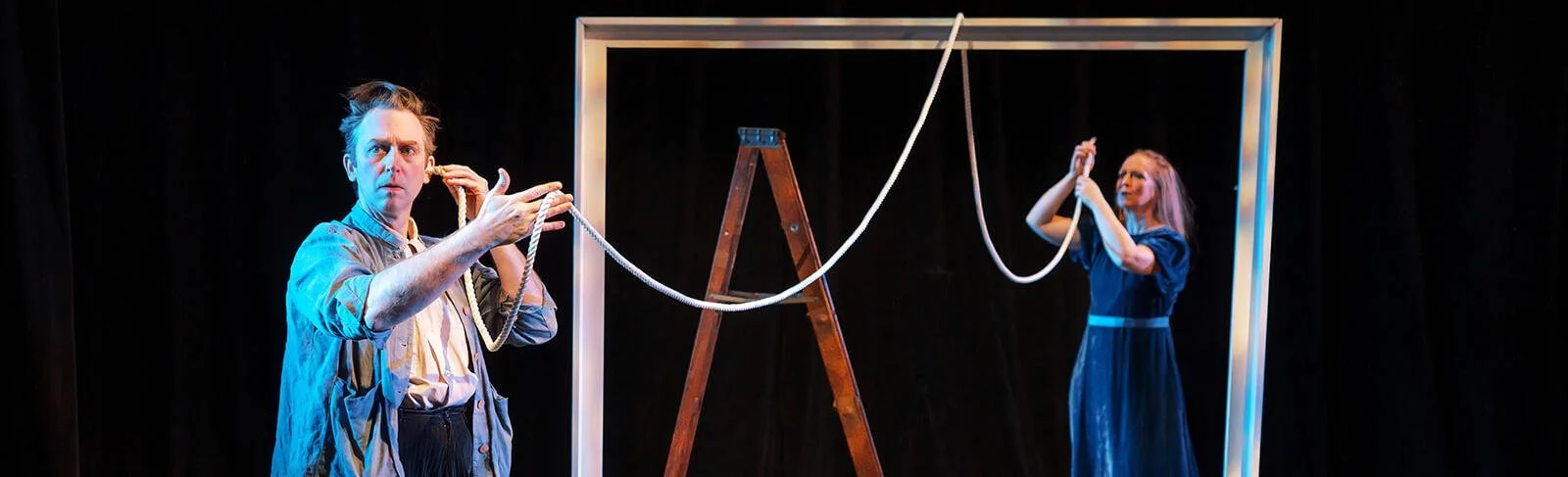

Secret Life of Humans

Like the Scottish-American songwriter with the same name, British playwright David Byrne is concerned with life during wartime, and captivated by one of life’s great questions: “Well, how did I get here?” In this coolly cerebral and beautifully staged production of Secret Life of Humans, Byrne, who codirects with Kate Stanley, transports us through the present day, the 1940s and the 1970s, with pit stops at the dawn of humanity. He explores a one-night stand, a marriage abruptly ended and, of all things, the darkly ironic and secretive career path of real-life mathematician Jacob Bronowski. As fuel for the fire, Byrne pulls big ideas from historian Yuval Harari’s bestseller, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, as well as Bronowski’s 1973 BBC series, The Ascent of Man.

Operation Crucible

“Bang.” “Bang.” “Turn.” “Brush.” Apparently that’s how steel gets made, or got made in World War II, with two men pounding it, one positioning it, and one more readying it for the next step. And a lot of steel gets made in Operation Crucible, Kieran Knowles’s vigorous retelling of the Sheffield Blitz, a 1940 calamity in the South Yorkshire town. Part-documentary, part-character study, and all-teamwork, this four-man entry into 59E59’s Brits Off Broadway series is energetic and affecting, and a little disorganized.

A Brief History of Women

Alan Ayckbourn’s latest play, A Brief History of Women, has the recognizable hallmarks of the best plays in his vast repertoire. His knack at dissecting and satirizing British society is unparalleled (Anglophiles will particularly enjoy them, but they’re accessible to all). There is the great British obsession with class, along with Ayckbourn’s distinctive mastery of exits and entrances familiar from The Norman Conquests, Communicating Doors, and the double bill of House and Garden. There’s poignancy, too, since the new comedy—the title is a bit of misdirection—is an homage to one man’s affecting life.

Replay

“Dodgy prawns,” insists the narrator in Replay, the affecting solo show written and performed by Nicola Wren, were the cause of her violent physical reaction upon hearing of a man’s suicide. It wasn’t pregnancy or anything else. The narrator, a woman police officer (identified only as W in the program), assures the audience that she is made of sterner stuff than to be shaken by the emotional impact of meeting the wife and daughter of the man, who took his life earlier that day. Dodgy prawns: This is her story, and she is sticking with it. As W describes in painful detail the personal turmoil surrounding her visit to the London home, one begins to suspect the prawns may be receiving a bum rap.

Fossils

Bucket Club’s inventive Fossils is one of the quirkier Brits Off Broadway 2017 entries so far, with its plastic dinosaur people and range of questionable accents. If the script doesn’t equal the rich world that the company conjures through sound and light, the play is still a beautiful reminder of the diverse material that Britain’s robust training system and government arts subsidies can produce.

The Roundabout

British playwright J. B. Priestley is best known for An Inspector Calls, his 1945 play that Stephen Daldry revived in a revelatory production in 1992 in London and in 1994 on Broadway. There followed for the neglected Priestley occasional Off-Broadway revivals of his works: in New York, Dangerous Corner in 1995, and Time and the Conways in 2002, both family dramas that played with time, and The Glass Cage, a splendid family play set in Canada, presented by the Mint Theater in 2008.

Angel and Echoes

The theater has not been kind to the English port city of Ipswich lately. Alecky Blythe’s documentary musical London Road, a huge hit for London’s National Theatre and recently made into a film featuring a singing Tom Hardy (no, really), shows Ipswich’s working class to be petty and vindictive. In the revival of Henry Naylor’s Echoes, part of a double bill with new play Angel at the Brits Off Broadway festival, Ipswich is such a “dungheap” that it drives two women into the arms of religious extremists in Afghanistan and Syria. Compared to the hellscapes in which the women of Naylor’s “Arabian Nightmares” find themselves, though, Ipswich is the Garden of Eden.

A Gambler’s Guide to Dying

There’s a famous joke about a man who prays for years to win the lottery. He tries to live a righteous life and promises to use the money for good, but his prayers grow increasingly bitter. One day, as he’s leaving church, having given God an earful, the clouds part and a voice booms, “Hey, moron, you have to buy a ticket!” A Gambler’s Guide to Dying, which launches 59E59’s 13th annual Brits Off Broadway festival this week, is about a man for whom buying the ticket is more than good advice; it’s his life philosophy.

Consumerism Gone Mad

What would you do to get a home? How far would you go? What if it were free? These are just a few of the questions posed to the audience by Jill and Ollie, a young married couple at the center of Philip Ridley’s sharply satirical Radiant Vermin. If anyone ever thought rampant consumerism is an American phenomenon, look no further. Ridley takes strategic aim at relatively new spectacle in the UK and hits a bull’s-eye.

Playing Jill and Ollie, Scarlett Alice Johnson and Sean Michael Verey, along with the charming and talented Debra Baker, bring Ridley’s hilarious script to life. Jill and Ollie, who have a newborn on the way, intimate early on that they are not proud of what they’ve done, but they have received a letter from the "Department of Social Regeneration Through the Creation of Dream Homes" offering them a free home. The letter invites them to meet Miss Dee (Baker) at their new residence to receive the keys. After much back-and-forth, Jill and Ollie decide to meet her in the rundown, relatively empty neighborhood. Miss Dee arrives and produces the contract from a satchel that is very reminiscent of Mary Poppins’. Although they have concerns about the local homeless camps near the house, they sign the contract.

The antics begin the first night in their new home when Jill and Ollie hear someone in the kitchen downstairs. Ollie, who looks like he wouldn’t hurt a mouse, investigates wielding a brass candlestick. The fight with the intruder, who was rummaging for food, is brutal fun, with Verey showing off a gift for physical comedy: he chokes himself and pulls at his own hair before taking a fatal swipe at the intruder with the candlestick. The actor is affable and charming, yet quick and nuanced. Ollie runs to get Jill and, instead of finding a body, they return to find a brand-new kitchen, “the kitchen we saw in Selfridge’s!” But they quickly learn that “renovating” takes on serious implications.

Ridley is known for examining the darker side of humanity, and Radiant Vermin is no exception. There are few if any props, and yet between the detailed script and superb staging by David Mercatali, it is as if everything described is physically in place. Playing only against a solid white backdrop, Verey and Johnson not only portray their characters but also each neighbor as the houses begin to fill up around them and the “keeping up with the Joneses”-type conversations with the neighbors, about furniture and lighting, gardens and automobiles, builds to a mad pace. In order to “remodel,” Jill and Ollie lure more homeless in. The neighborhood becomes a hotbed of consumerism: the “Never Enough Shopping Centre” is opening nearby and their unfettered remodeling begins to tear at the fabric of their souls. Baker reappears as Kay, one of the homeless they have brought home. In a touching scene, she relates the rumors on the streets about people luring the homeless, who never return.

The crescendo, when Jill and Ollie are cajoled into throwing their son’s first birthday party for all the neighbors, is outstanding. Between Ridley’s fantastical writing, Mercatali’s direction, and Verey and Johnson’s acting, numerous neighbors come to life in a frenzy of mime, dialect, and comedic timing. Lighting choices by production designer William Reynolds heighten the frenetic dialogue at the birthday party. If occasionally amid the British accents some of the words are lost, the birthday-party scene is nevertheless priceless.

Verey and Johnson are the heart of this fast-paced black comedy, delivering Ridley’s satiric dialogue. He allows a peek behind the curtain of civility and jabs at human nature. It’s easy to see with Radiant Vermin just how seductive our buying habits become with just a little coaxing. If this is the best Britain has to export, long live Brits Off Broadway.

Radiant Vermin continues at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th St., between Park and Madison avenues) through July 3. Evening performances are at 7:15 p.m. Tuesday to Thursday and at 8:15 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2:15 p.m. Saturday and 3:15 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $35. To purchase tickets, call Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200 or visit www.59e59.org.

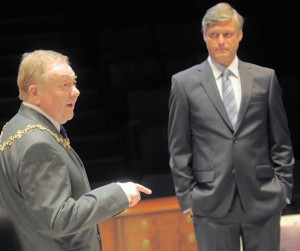

Home Town Unpleasantries

Alan Ayckbourn’s plays have been a fixture of the Brits Off Broadway Festival for several years. This year, along with a revival, the festival is presenting the world premiere production of Hero’s Welcome, first seen at Ayckbourn’s own Stephen Joseph Theatre in Yorkshire, England, and now on an international tour.

Ayckbourn, the author of 79 plays, may be one of the most underrated playwrights alive. Many of his works are comedies, but there are often dark underpinnings. From his classic Absurd Person Singular (1975), in which a hilarious attempted suicide takes up the entire second act, to Arrivals & Departures (2013), one of his darkest, he has been a masterly commentator on British society in plays that range from science fiction (Comic Potential, Communicating Doors) to astute social observation (Things We Do for Love, Absent Friends)—always using comedy to make his points.

Unlike many Ayckbourn plays, Hero’s Welcome feels a bit long and complicated. Opening with Elgarian music and a TV interview, it concerns a soldier named Murray (Richard Stacey) who has returned to his small home town to take up residence with his new wife, a woman from the unidentified foreign country in which he conducted his heroic deeds. Her name is Madrababacascabuna, but she goes by Baba. The interview elicits a confession from Murray that he left under a cloud; he was “a bit of a tearaway,” as his interviewer puts it. As Ayckbourn’s play unfolds, it becomes clear that the heroes in the play are the three wives we see; their husbands are cruel or ineffectual. The mayor of the town, Alice (Elizabeth Boag), was abandoned at the altar by Murray. Now she is matched with a kind-hearted duffer named Derek (Russell Dixon), who plays with toy trains all over their house, and who describes himself as a “consort.”

Murray’s old mate Brad, meanwhile, is married to Kara. But the upper-class, wealthy Brad refuses to acknowledge that he and Murray were close childhood friends. The competitive Brad is, in Wodehousian terms, a blackguard. He repeatedly insults Charlotte Harwood’s cheery, giggly Kara, and she accepts it.

Murray hopes to resurrect the family business, an old hotel called the Bird of Prey. It’s listed as historically important but is rundown. Moreover, Murray’s father couldn’t pay the taxes on it, and now it belongs to the town council, and Alice is bent on tearing it down. Although she’s not vicious, it suits her impulse for revenge to prevent Murray’s buying back the property.

Ayckbourn’s play is about the public faces people put on that conceal their private personalities, and how the past shapes those personalities. Just as Kara remains chirpy in order not to recognize Brad’s cruelty, Brad himself is cruel in order to forget his lack of courage in throwing over a woman he loved in the face of his parents’ threat of disinheritance. Murray, meanwhile struggles with some bad behavior of his own. In addition to jilting Alice, his heroism is a sham.

It’s often unwise for an author to direct his own work, but in the past Ayckbourn has proved the rare exception to the rule. This time, though, the play feels a bit longer than it need be, and a bit overstuffed with incident. What a different director might have done to tighten it is uncertain, but the actors, at least, are outstanding. Stephen Billington’s Brad is all surly arrogance, and Boag’s Alice is stiff and competent, but frosty from a life of suspicion sparked by her jilting. Dixon is a comic pleasure, and Derek’s rising to his Lochinvar moment, when he excoriates Brad, is deeply satisfying. Stacey’s Murray is perhaps the least interesting character—he’s not the hero of the title, since it’s an ensemble piece—but he conveys decency, modesty and honest regret.

Still, it’s Evelyn Hoskins’ Baba who is first among equals. Learning English slowly and painstakingly, bravely facing a future in as a refugee, ultimately befriending Kara and confronting Alice, Baba’s journey becomes the play’s real focus. Early on, after she has met the people from Murray’s past, she asks him: “Why they hate you?” Like Winnie in the Ayckbourn masterpiece My Wonderful Day (2009), she knows the truth that others cannot see.

Two Alan Ayckbourn plays, Hero’s Welcome and Confusions, run in repertory through July 3 at the Brits Off Broadway Festival at 59 East 59 St. between Park and Madison. Tickets are $70 but two-show packages are available. For information, visit 59e59.org.

Truths Be Told

The British have a way of turning the everyday inside out in a humorous way. Confusions, written and directed by Alan Ayckbourn, and part of the Brits Off Broadway festival, is a masterly series of vignettes in which characters try hard to maintain normalcy and decorum, but when a single truth is revealed through an ill-timed but dramatically funny mishap, a more personal and meaningful internal world is uncovered. The cast of five—Elizabeth Hoag, Charlotte Harwood, Stephen Billington, Richard Stacey and Russell Dixon—skillfully play a handful of characters.

In “Mother Figure,” Lucy (Elizabeth Hoag) is a harried and all-consumed mother who doesn’t pay much attention to the ring of the phone, the doorbell, and thus the outside world. When her neighbors, Terry (Stephen Billington) and Rosemary (Charlotte Harwood), stop by to check on her for her husband who is away, she can’t seem to carry on a simple conversation. Instead, she offers juice to Rosemary and milk to Terry, to which he defiantly claims he “hates the damned stuff.” She counters: “I’m not going to waste my breath arguing with you, Terry. It’s entirely up to you if you don’t want to be big and strong.” Terry doesn’t have a clue how to respond. When Terry drinks all of Rosemary’s juice and then insults her, the moment uncovers some bigger marital problems. Lucy, undaunted, doesn’t believe anything can’t be solved with simple directives, and orders Terry to say he’s sorry to Rosemary. Reduced by her stern mother figure, they kiss her good-night before they leave, and when she tells them to hold hands while crossing the street, they oblige, and one feels all has been restored.

“Drinking Companion” shows Lucy’s husband, Harry (Richard Stacey), a traveling salesman who feels his wife is happier when he’s away. Desperate to connect with another adult, particularly a woman, he makes a show of being friendly with Paula (Charlotte Harwood) at the hotel bar. He struggles to pump himself up when he talks about his line of haute couture and colors, but all he really wants is companionship. As he grows drunker he tries not to make advances, but puts his key on the table, and says, “I’m going to leave it there. I’m not going to try and embarrass you, you see, but its there. If you want to pick it up, it’s there. Entirely up to you.” When he goes out to call a cab, Paula and her friend slip away. Poor Harry.

Ayckbourn also captures how communication is about energy and not necessarily words. In “Between Mouthfuls” two separate couples dine at a restaurant under the pretense of having a pleasant evening out. However, their conversations soon turn to jealousies. As things intensify, they continue their argument even when the sounds of their voices drop away. Their jaws, working out the tension around the words, still speak volumes.

Sometimes a small reveal can have big consequences. This is especially true in “Gosforth’s Fete” in which Milly (Charlotte Harwood) is setting up for tea in a tent to celebrate the visit of an important patron. There are many problems that day, including a mute loudspeaker. Gosforth, the organizer of the event and local pub owner, tinkers with the loudspeaker during a conversation with Milly. Unbeknownst to them, he gets it to work at the same time that Milly reveals her news. It’s a cringeworthy yet funny moment because it’s the kind of timing you know can happen but wish it wouldn’t. Milly’s fiancé Martin (Stephen Billington), a Boy Scout leader, is so overwrought from the inadvertent revelation he gets drunk on sherry. In the end, Milly sizes him up and declares that she doesn’t like his baggy shorts anymore, anyway.

Capping the evening, “A Talk in the Park” brings the ensemble together. Each character wants to enjoy the park alone for various, personal reasons. With only four park benches and five characters, one is bound to join another. In a round robin of sorts, one sits next to another, thus intruding on their solitude. However, as much as these people want to be left alone, they don’t hesitate to complain about the person who was “talking too much” to the occupant on the next bench when they move. It turns out they can’t help talking too much as well, and thus the initial occupant moves to the next bench. And so the circle continues. The scene captures both the inside and outside aspect of our desires to be alone, yet at the same time to share and unburden the troubles we carry in our hearts and minds.

Confusions by Alan Ayckbourn is part of the Brits Off Broadway festival and is playing through July 3 in repertory with Hero's Welcome at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th St. in Manhattan). Tickets are $70 and may be purchased by calling Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200 or visiting www.59e59.org, where the repertory schedule may also be seen.

She Won the Lottery

Originally published as a paperback, Ross & Rachel is a tightly written tour de force for Molly Vevers, who easily modulates between “he” and “she” in this fast-paced drama. Fritz raises a number of questions and challenges about being in a relationship from the moment two people meet and how they interact with others at a party. Imagine a couple, not so much as individuals but as a couple conversing with others, practically talking over each other in side-by-side dialogues.

“How long have you two been together now?”

“You’ve still got that look about you.”

“Did you ever hear how we first met?”

“Right from the first moment I saw her, standing next to my sister, I knew.”

“Not now, honey.”

“Strap yourselves in, you’re not gonna believe this story.”

“They don’t want to hear about that.”

“You guys think that’s good? Tell them about how we got back together. She tells it better than I can.”

Vevers delivers this type of dialogue consistently for nearly 60 minutes. She is quite good in this challenging role, especially as the subject matter evolves into difficult, almost unimaginable events. A number of inquiries are examined and played out. Where does “I” end and “you” begin? Just how much will women often give up to be in relationship? Is it true that any man is better than no man? Does “until death do us part” really mean what it says?

Fritz wrote the male character as a typical guy. However, a revelation of an illness he has leads to a demand of her that seems hugely selfish. But the "Ross" character (those names are never heard throughout the work) doesn't seem written egotistically enough to warrant her acquiescence to his request. Or is she just mad?

Vevers begins the performance dressed only in a white cotton waffle-weave spa robe, holding a cup of tea and sipping from it casually as if to have a chat. Eventually she pours the remainder into the shallow pool she is standing in. She then fills the cup from the pool and proceeds to drink from it three times, spitting out the rancid water each time. Cringeworthy, but to what end? The action yanked the focus from the dialogue.

The design elements don’t help much. The lighting design by Douglas Green don’t live up to Vevers’ performance. Lighting appears as an afterthought—almost nonexistent light and a strand or two of twinkle lights hang overhead. Only at one point was the light dramatic enough to complement the brutal dialogue—when Vevers is lit crosswise, creating two distinct shadows on opposite walls. Alison Neighbor has designed a set featuring a shallow, round, black pool of water—which Vevers never leaves after the first 10 minutes or so—surrounded by eight votives on the floor.

To complete the play, director Thomas Martin has Vevers clap three times. The lights go to black, as if it were the “Clapper” lighting commercial or Jeb Bush begging an audience with “You can clap now.” Cue music. Vevers is too fine an actress and the dialogue too complex to incorporate silly moves and allow for a nonsensical set design—it’s unnecessary and distracting.

Ross & Rachel is strong and powerful, and it demands attention, and Vevers brings the words alive. What is striking is her drive to connect with each audience member, most telling in a monologue about coffee. She has a manner and a presence reminiscent of fine actresses from another era. This is her era, her time.

Ross & Rachel is part of Brits Off Broadway at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th St., between Park and Madison Avenues). Performances run through Sunday, June 5. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday and 8:30 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Saturday and 3:30 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $25 ($17.50 for 59E59 members). To purchase tickets, call Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200 or visit www.59e59.org.