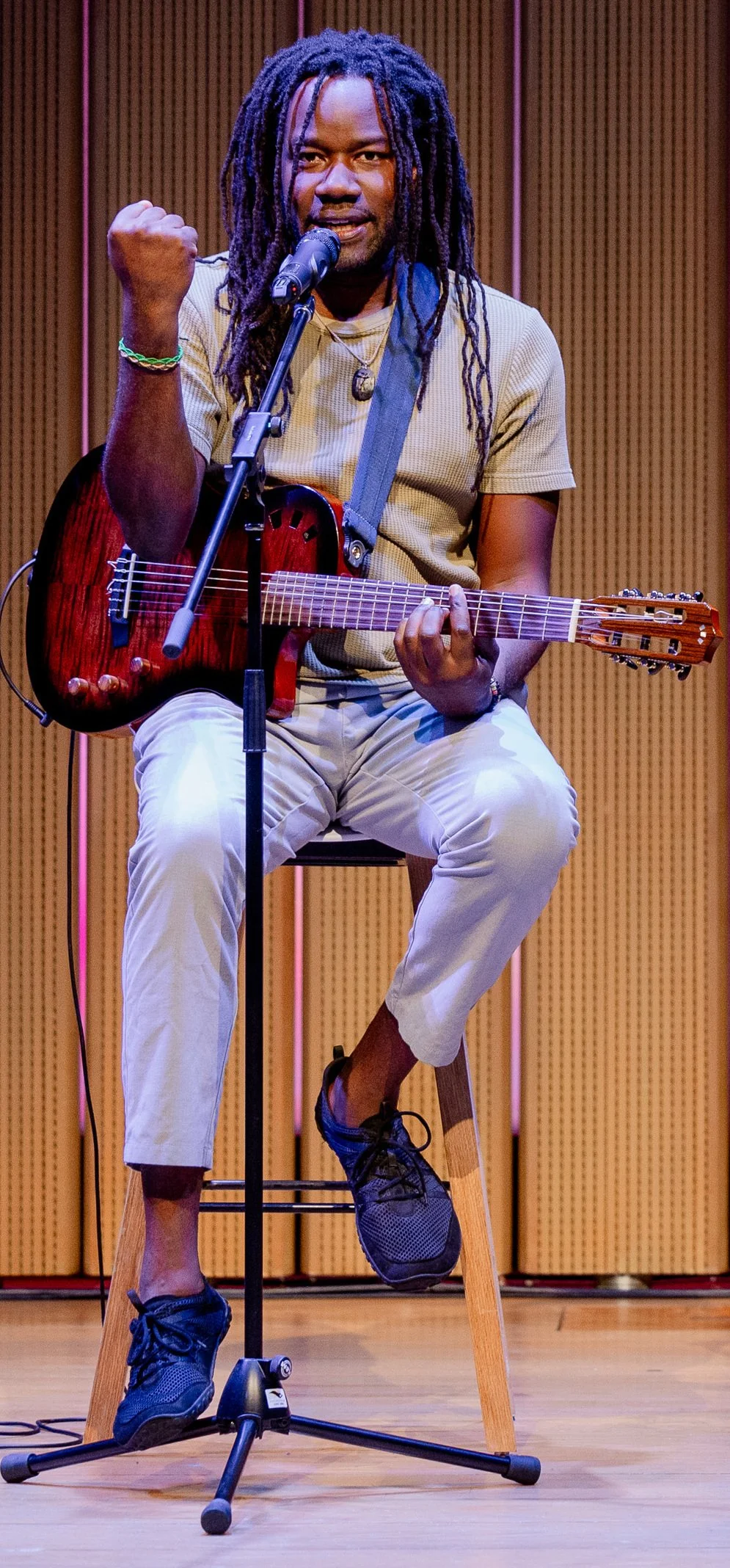

Singer, songwriter, and playwright Duane Forrest traces the life and legacy of Bob Marley in his soulful solo show, “Bob Marley: How Reggae Changed the World.”

Bob Marley: How Reggae Changed the World is a soulful solo journey that traces reggae’s roots and its global reverberations through the life and legacy of its most iconic figure. Written, performed, and directed by Duane Forrest, the show blends acoustic music, personal storytelling, and audience connection, allowing one to glimpse how Bob Marley’s message reshaped not only a genre, but lives.

Forrest sensitively performs many of Marley’s greatest anthems in his one-man show, including “No Woman, No Cry” and “Redemption Song.”

When the lights come up, Forrest and his guitar command the stage with “Jammin’,” one of Marley’s most beloved anthems, its message of unity and resilience setting the evening’s tone. Although Forrest performs 16 songs over the course of the show, this opening choice feels especially apt, balancing the song’s communal optimism—“Let’s get together and feel all right”—with its darker resolve: “No bullet can stop us now,” a pointed reference to the 1976 assassination attempt on Marley; his wife, Rita; and manager Don Taylor at their home in Kingston, Jamaica. Later, Forrest returns to the incident, noting that Marley appeared just days afterward at the Smile Jamaica concert, performing in spite of a fresh bullet wound—an act that crystallized his mythic stature.

From this musical invocation, Forrest offers a cradle-to-grave portrait of Marley’s life, interweaving songs, narrative, and his personal reflections on the legend and his music. He begins with the essentials—“Robert Nesta Marley was born May 11, 1945, in Nine Mile, up in Saint Ann Parish,” in Jamaica before relocating as a youth to Kingston’s Trench Town—and traces Marley’s musical awakening alongside Bunny Wailer (Neville “Bunny” Livingston) and Peter Tosh (Peter McIntosh). Their informal education came under the guidance of Joe Higgs, whom Forrest describes as a “streetwise singer and musician, like their own private music professor.” Training beneath a mango tree, the young artists honed harmonies and phrasing while absorbing influences ranging from Curtis Mayfield and the Impressions to American soul groups such as the Drifters, the Platters, and the Temptations—sounds that would quietly shape reggae’s emerging voice.

Forrest reveals himself to be a fountainhead of knowledge about reggae’s origins and evolution. He notes that one of the earliest uses of the word appears in the song “Do the Reggay,” carefully spelling it out—R-e-g-g-a-y—before posing a playful challenge to the audience: Does anyone know who wrote or performed it? A brief silence settles over the intimate SoHo Playhouse before Forrest supplies the answer himself—Toots and the Maytals—adding that the group was a major influence on Marley and that the song embodies reggae’s irrepressible joy. He then launches into his own soulful rendition of the 1963 track, inviting the audience to join in on its buoyant call-and-response refrain, an invitation that many accept.

Clenching his fist, Forrest reminds the audience that Marley sang songs of defiance, in hopes of ending racism and oppression of the poor. Photographs by Weiwuying National Kaohsiung Centre for the Arts.

Yet the evening is far more than a concert—or a lecture. Reggae, for Forrest, is sustenance: music as nourishment for those who hunger for freedom.

Born in Toronto to Jamaican parents, he recalls reggae as a constant presence in his household, its rhythms shaping his earliest memories. He traces his lineage to West Africans transported to Jamaica through the slave trade before his ancestors later emigrated to Canada, and shares a telling adolescent anecdote: assigned to create a family tree, he was unable to complete it and sheepishly told his teacher that the dog had eaten his homework—a small moment that quietly exposes the enduring scars of displacement.

Growing up in a risky neighborhood in Scarborough, Ontario, was not easy, Forrest says. Music became a lifeline, offering an escape from the paths that trapped many of his peers. With understated pride, he notes that reggae has since carried him to more than 30 countries, performing across the globe, before adding that bringing this solo show to New York fulfills a long-held dream.

The show also allows Forrest to introduce one of his own reggae songs, “The Bluffs,” inspired by a Toronto neighborhood. Though he jokes that the song failed to save a romantic relationship, its real triumph, he suggests, was proving that he could write reggae of his own.

By the time the evening draws to a close, Bob Marley: How Reggae Changed the World has earned its place as the opening salvo of the 2026 International Fringe Encore Series, a showcase that serves as a stepping stone for exceptional, emerging theater artists. Forrest reminds one that Marley—the creator of enduring anthems like “I Shot the Sheriff,” “No Woman, No Cry,” and “Redemption Song”—died at just 36 from skin cancer, an untimely end for a freedom fighter whose music continues to resist silencing. What remains, as Forrest makes clear through song and story, is not loss but transmission: reggae as a living force, still calling listeners to unity, justice, and hope.

Bob Marley: How Reggae Changed the World plays through Feb. 1 at SoHo Playhouse (15 Vandam St.). Performance dates and times are irregular and may be viewed, along with other information, at sohoplayhouse.com.

Playwright & Director: Duane Forrest

Producer: John McGowan & Laura McCloud

Dramaturg: Ins Choi