If you didn’t know that A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur was by Tennessee Williams, you might easily guess it. When the critic John Mason Brown reviewed A Streetcar Named Desire in 1947, he noted that play’s similarities to The Glass Menagerie: “Mr. Williams’ recurrent concern is with the misfits and the broken; with poor, self-deluded mortals… If they lie to others, their major lie is to themselves. In this way only can they hope to make their intolerable lives tolerable. Such beauty as they know exists in their dreams. The surroundings in which they find themselves are once again as sordid as is their own living.” Brown might have written the same words about Creve Coeur, first produced in 1979.

Its two main protagonists are Dorothea (“Dotty”), a young teacher, and an older woman, Bodey, from whom she rents a space in a cramped apartment (vividly evoked by Harry Feiner as a warren of furnishings with a smash of colors). The other two characters are Helena, a well-dressed, determined woman with a plan to upset the arrangement and Miss Gluck (Polly McKie), an emotional mess in a bathrobe. Her mother has recently died, and she thinks her upstairs apartment is haunted and keeps dropping down to see the sympathetic Bodey.

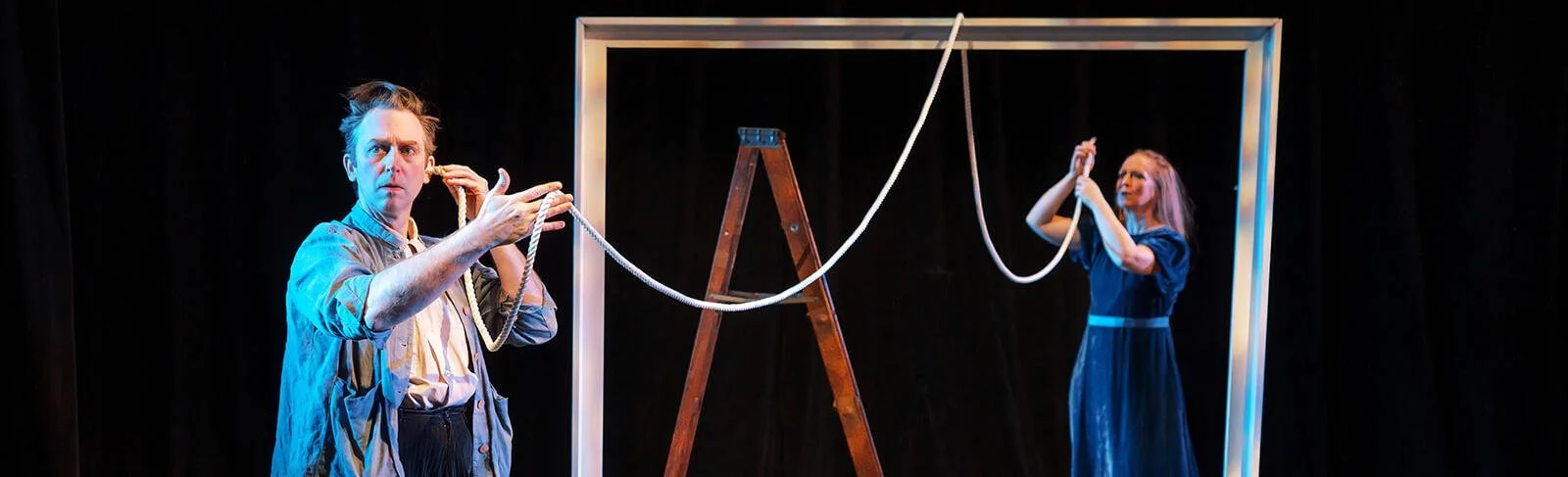

Kristine Nielsen (left) is Bodey and Jean Lichty is Dotty in Tennessee Williams’s A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur. Top: Nielsen and Lichty with Annette O’Toole as Helena.

Produced by La Femme Theatre Company, “dedicated to the exploration and celebration of the universal female experience,” Creve Coeur doesn’t have the more experimental elements of Williams’s late plays, nor even the framing device of A Glass Menagerie—although Creve Coeur is set in St. Louis, in the 1930s—but the delusions are present.

Dotty (Jean Lichty, founder of La Femme) is a struggling schoolteacher who rents space in a cramped apartment as she’s waiting for something better to turn up, specifically a phone call from Frank Ellis, the flashy high school principal who has taken her out.

Bodey (Kristine Nielsen), the landlady, is a dynamo who cooks, sympathizes and tries to interest Dotty in her brother, Buddy. Bodey has planned a regular Sunday outing for Creve Coeur, where there’s an amusement park, and she hopes Dotty will go. Buddy will be there.

Dotty knows that Bodey is playing matchmaker, despite Bodey’s denials, and she tries to emphasize her lack of interest in Buddy: “He simply isn’t a type that I can respond to…In a romantic fashion, honey. And to me, romance is—essential.” Fans of Williams can foretell there’s going to be heartbreak (crève-coeur is French for “heartbreak”), even if Dotty is shrewd enough to see past Bodey’s machinations, in Williams’s lyrical description of a grim future: “You’ve been deliberately plotting to marry me off to your brother so that my life would just be one long Creve Coeur picnic, interspersed with knockwurst, sauerkraut—hot potato salad dinners.”

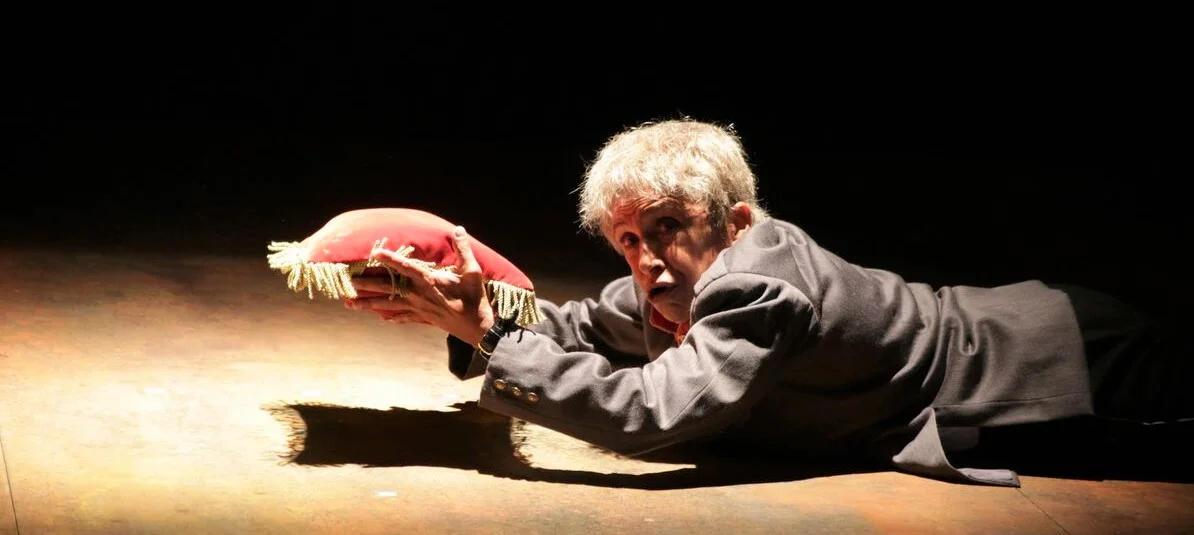

Nielsen with Polly McKie as Miss Gluck. Photographs by Joan Marcus.

In spite of the lyricism, though, Williams’s extended back-and-forth between the two women feels laborious, and director Austin Pendleton, who does a fine job otherwise, makes a crucial mistake by having Bodey read a notice in the newspaper and throw it to the ground, unnoticed by Dotty; you can almost predict in the first moments that the paper has an engagement announcement involving Ellis. The action hangs like an albatross on the already repetitious dialogue of the first half.

Things pick up when Helena arrives. Annette O’Toole is a smartly dressed social climber who teaches at Dotty’s school; she has found an apartment but needs Dotty to share expenses. It’s the clash between Helena and Bodey that provides the interest.

From the start, the elegant, supercilious Helena is thwarted by Nielsen’s tough broad, and you can’t help but root for Bodey as she prevents the pushy intruder from walking all over her—even suggesting a possible physical opposition. Nielsen expertly navigates the kindness, toughness and self-delusion of her character while finding unexpected comic moments. O’Toole, too, though easy to dislike, makes Helena more than a mere snob; she is also a woman with dreams who is too proud to admit she needs a helping hand. Lichty charts Dotty’s slow disintegration of confidence and her growing fragility and frustration, but her Dotty never implodes, even when her hopes are dashed. McKie, in a part that requires little English but expertly accented German, excels in making the weepy Gluck memorable.

Ultimately, it’s the actors who refresh the tired themes of this late Williams drama. Williams fans who rarely have the chance to see his lesser plays in good productions will welcome this opportunity.

La Femme’s production of A Lovely Sunday for Creve Coeur plays through Oct. 21 at Theatre at St. Clement’s (423 West 46th St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday and at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $55–$99 and may be purchased by calling (866) 811-4111 or visiting lafemmetheatreproductions.org.