Martin McDonagh is riding high now on the success of his second feature-length movie, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, but he first made his mark in theater in the 1990s with several pitch-black comedies, notably The Beauty Queen of Leenane and The Lieutenant of Inishmore, which raised bloodletting to high art. He has a Jacobean gift for slapping together murder and guffaws.

Imperfect Love

Imperfect Love is a “serious romantic comedy” loosely based on the life and work of the 19th-century Italian actress Eleonora Duse and her nine-year love affair and tumultuous working relationship with the poet and playwright Gabriele D’Annunzio. Set in Rome on the stage of the Teatro Argentina in Rome in 1899, the plot of Brandon Cole’s two-act period play follows the backstage dramas of a theater company struggling to produce a new work.

Miles for Mary

Miles for Mary, the sly new play at Playwrights Horizons, has a lengthy writing credit: “Written by Marc Bovino, Joe Curnutte, Michael Dalto, Lila Neugebauer and Stephanie Wright Thompson in collaboration with Sarah Lunnie and the creative ensemble of Amy Staats & Stacey Yen.” That credit may be accurate, but it’s also a wink at the audience. Miles for Mary is a comedy about a committee at a high school, and, defying dire axioms about things done by committee, it’s a hoot.

He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box

For the past half-century, Adrienne Kennedy has carved out a unique niche for herself in the American avant-garde. Her one-act plays, such as Funnyhouse of a Negro (1964), A Rat’s Mass (1966) and Ohio State Murders (1992), are dense with allusions to pop culture, especially the movies, and fascinated with European royalty. Though riffing on Shakespeare and Greek tragedy, they are often semi-autobiographical, animated by Kennedy’s experiences as a black woman in America but shaded by her time abroad in Ghana and London. Elliptical and surreal, they cut right to divisions and hypocrisies at the heart of American society. He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box, Kennedy’s first new play in a decade, may be her most narratively straightforward work yet, but even at a svelte 45 minutes it is no easily digestible scrap.

Fire and Air

It’s some feast that Terrence McNally has cooked up for Douglas Hodge, fulminating and relishing every minute as the tortured, torturing ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev in Fire and Air, a premiere at Classic Stage Company. McNally has always been fond of larger-than-life personalities gesticulating wildly and playing to the wings—think Master Class, The Lisbon Traviata, It’s Only a Play. He has often toiled in the opera realm, addicted to its outsize theatricality and the strong feelings its fans and its creators harbor. With Fire and Air he switches to ballet, specifically the Ballets Russes on the eve of revolution—an art where those qualities also abound. The author is 79, he has written plays for more than half a century, and Fire and Air is vintage McNally.

The Homecoming Queen

Don’t go to The Homecoming Queen expecting a story involving tailgate parties and Hail Mary passes. This thoughtful, emotionally wracking drama doesn’t even take place in the United States. It’s the story of a homecoming of its heroine, Kelechi, to the African village in Nigeria that she left 15 years earlier to build a life in the U.S. It’s about culture shock, revenge, guilt, and, strangely but pertinently, the damage wrought by rape.

Jericho

Michael Weller’s lengthy program note for Jericho, a reworking of Ferenc Molnár’s play Liliom, acknowledges that it failed when first produced in 1909. He notes “it’s [sic] inventive and unexpected story, blend of crime, romance, fairy-tale” and “off-center mordant humor,” along with “a love story like no other I know of.” Audiences will recognize the plot of Carousel: Rodgers and Hammerstein took the play, which became a Theatre Guild hit in 1921, and used it as the basis for a more far-reaching success.

The Thing With Feathers

Scott Organ’s opening scene for The Thing With Feathers is deceptively creepy for anyone attuned to the dangers of the Internet. A young girl, Anna (Alexa Shae Niziak), is sitting on her bed, with paperwork around her, and she’s talking to a man named Eric—someone she has never met. They have clearly bonded online over poetry, particularly Emily Dickinson. They recite stanzas of Dickinson’s “Life” to each other: “For each ecstatic instant/We must an anguish pay/In keen and quivering ratio/To the ecstasy.” The voice gently probes elements of her home life and her relationship with her mother. The scene promises a literate, solidly structured drama, and it delivers.

A Kind Shot

In basketball, as Terri Mateer instructs in her solo show, a kind shot is one that touches nothing but net. No bouncing off the backboard, no clanging around the rim, just a sphere on a pristine trajectory that ends with a satisfying swish. Basketball was an integral part of Mateer’s high school, college, and young adult years, but the arc of her life was anything but clean. In an extended monologue that at times devolves into a bull session with the audience, then pivots into entertaining b-ball play-by-play, she recounts how the loss of her father gave way to a series of mentors, some wanting to help her, others wanting to help themselves to her. Though the dialogue could stand some tightening, and a director could help Mateer better realize the moments that call out for a pause, her saga, her stage presence and her intimate style of delivery bring home a win. The fact that her story is also one of outracing relentless sexual harassment, shows that her cultural timing is as strong as the pass timing of her youth.

X: Or, Betty Shabazz v. The Nation

X: Or, Betty Shabazz v. The Nation by Marcus Gardley is not only a portrait of Malcolm X, the optimistic and eloquent civil rights leader who was assassinated in 1965, but also of a dangerous and tumultuous time. In Gardley's play, time and place dissolve from one scene into another—a courtroom, the home of Malcolm (poignantly played by Jimmon Cole) and his wife, Betty Shabazz (Obie winner Roslyn Ruff), as well as the street; an office; and the home of Elijah Muhammad, leader of the Nation of Islam. In all the scenes Gardley focuses on a question that dominates the court: who killed Malcolm X?

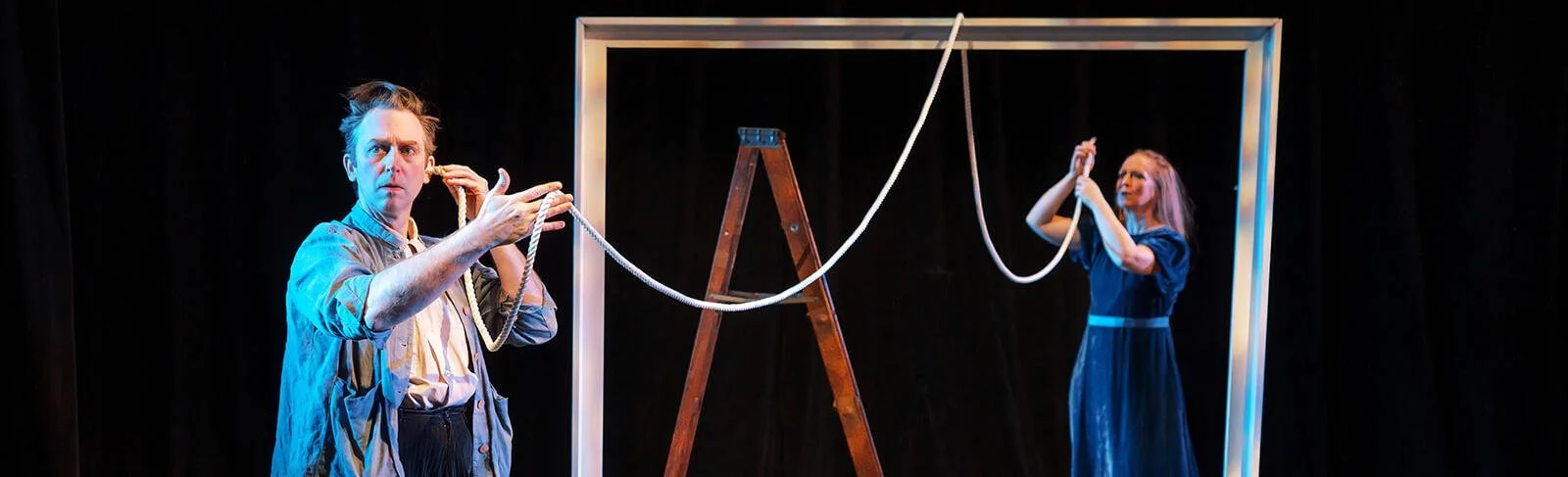

The Undertaking

Now in their 17th year, The Civilians have etched out a unique place for themselves in the New York theater scene. Employing what they refer to as “investigative theater,” company members gather source material as journalists, then transform their research into art. In The Undertaking, two performers, portraying multiple characters, enact real-life interviews centered on the act of dying. Lip-syncing, film appreciation, a small warehouse of electronic devices and a pillow fort are all utilized as the characters take an inward trip to the hereafter and expound on shuffling off this mortal coil. All the while, the production comments upon itself and divulges its own techniques. Death may be the subject of this play, but its theme is creation.

Hindle Wakes

Stanley Houghton’s bracingly unsentimental Hindle Wakes failed twice on Broadway, expiring after 30-odd performances in both 1912 and 1922. In a new century, the Mint Theater Company is demonstrating that this little-known play with its perplexing title is a compelling period piece. Directed by Gus Kaikkonen and performed with unrelenting gusto, Hindle Wakes is likely to prove more enduring this time around.

Disco Pigs

Disco is one of those words that the senses respond to instantly with several very particular references: late 1960s or early ’70s New York City spring to mind. However, the world of Disco Pigs is a far cry from that, and disco assumptions are turned on their head. Enda Walsh’s play strips the term bare of its bright-lights, big-city ballroom connotations, throws a hefty dose of punk into the trunk, then turns off-road onto the aimless side of life. But it does so with deep, dark humor, wide-eyed invention and heaps of passion.

The LaBute New Theater Festival

The LaBute New Theater Festival is one of the rare times that one-acts get center stage (along with Author Directing Author, playwright Neil LaBute’s annual presentation of one-acts by him and Italian playwright Marco Calvani). The current trio of offerings provide two very strong entries and one, unfortunately, that isn’t. It’s the short-form champion’s own curtain-raiser that is the disappointment.

Counting Sheep

Counting Sheep is immersive theater at its very best. Billed as a “guerrilla folk-punk opera,” the work is about the 2013–14 Ukrainian Revolution in Maidan Square, in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev. And it is into the arms of this revolution (also known as the Revolution of Dignity), as it spreads from the youth to Ukrainian people of all ages, that the members of the audience are thrust.

De Novo

Imagine the life of a young lad who was never told that he was a good kid. “From the time [Edgar Chocoy] was born,” says immigration defense lawyer Kimberly Salinas (Emily Joy Weiner) in the documentary-theater piece De Novo, “he was seen as this poor kid from the slums of Guatemala City, then a gang kid from East L.A., then a criminal alien teenager in Immigration Court. I don’t think anyone ever got to see who he really was.” Salinas’s reflection makes clear that a seemingly trivial detail such as this can impose serious implications on a person’s self-esteem and that a life can sustain enormous consequences from it.

Downtown Race Riot

Only moments into Downtown Race Riot, playwright Seth Zvi Rosenfeld skillfully plunges the audience into a milieu that Republicans in the current political landscape fulminate over. An indigent mother (Chloë Sevigny), advises her son Pnut (pronounced peanut) that she has a foolproof plan to earn money, but she will need his help when her lawyer comes by shortly. “Listen to me,” she says, “I’m gonna bring up your asthma so have your inhaler ready and if you have to fake a cough, be prepared…. And you may have to act mildly retarded.” With a sluggish indifference, unless she’s animated by a new scam, Sevigny expertly inhabits her character, Mary, with her semi-glassy eyes (she’s a recovering addict, and not too far on the road to recovery to turn back decisively) and a confidence in her own craftiness.

20th Century Blues

Aging is the lens through which Susan Miller’s 20th Century Blues explores the relationships of four women who have known one another for 40 years. The play focuses on the baby-boomer generation and zooms in on how they deal with themselves, their friendships and their social status.

Harry Clarke

Billy Crudup has built a career playing charming rogues in films like Almost Famous, Eat Pray Love, and last year’s 20th Century Women. It makes perfect sense when his character is revealed as (11-year-old spoiler alert!) the real villain of Mission: Impossible III because Crudup is credible as both hero and villain; there’s always a hint of psychosis underpinning his boy-next-door looks. He’s indulged this duality in his stage roles as well (The Elephant Man, The Pillowman, The Coast of Utopia), but none has exploited the dark under his light as successfully as Harry Clarke, David Cale’s new one-man show at Vineyard Theatre.

Hot Mess

A retitled version of Regretrosexual—The Love Story, a play written roughly 10 years ago by Dan Rothenberg and Colleen Crabtree, the “new play” Hot Mess is about the authors’ unusual courtship and marriage. Both were comedians working in Los Angeles, and the work focuses on a particular hurdle Rothenberg had to overcome: he had lived as a gay man for two years in San Francisco before meeting and marrying Crabtree. Scrubbing out the “regret” part of the former title and using the catchier Hot Mess eliminates the implication of previous disappointment in the age of political correctness.