Kait Kerrigan and Brian Lowdermilk are the Rihanna of musical theater. Just as the Barbadian pop goddess releases hit song after hit song while selling relatively few albums, Kerrigan and Lowdermilk are less known for their plays than for their individual tunes, which have gained them a rabid online following. Their contemporaries Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (Dear Evan Hansen, La La Land) have conquered Broadway and Hollywood, but Kerrigan and Lowdermilk have connected with the millennial fan base like no other musical theater writers; they’re the official composers of the Internet. Now, several of their conversationally catchy pop songs have found their way into the long-gestating original musical The Mad Ones, playing at 59E59 Theaters.

Peter Pan

The boy who wouldn’t grow up has become the character who won’t die. J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan has been endlessly staged, filmed, remixed, twisted, and contorted since its 1904 premiere at the Duke of York’s Theatre, London, and the insatiable Pan pangs show no sign of ceasing. Bedlam’s current adaptation at another Duke, on 42nd Street, is the second Peter Pan–inspired show to run on the Deuce this season.

The Home Place

The “home place” in the title of Irish playwright Brian Friel's 2005 drama is Kent, England, where the family of widowed landowner Christopher Gore (John Windsor-Cunningham) originated. Gore, residing in Ballybeg, Ireland, speaks of Kent as a paradise lost, though he’s never really lived there. He and his son David (Ed Malone) administer their Irish estates with an uneasy liberality toward their tenants, made all the more uneasy by the recent murder of another local English landlord.

Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train

New York Congressman Adriano Espaillat has called it “an 18th-century solution to a 21st-century problem.” New York City Mayor Bill De Blasio has vowed to shutter it in the next decade. Most people don’t think about it unless they’re flying out of LaGuardia, but many don’t have that luxury: Rikers Island, the bête noire of the East River, is one of the largest and worst prisons in America and a hotbed of violence and neglect. Stephen Adly Guirgis’ 2000 play Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train, in revival at Signature Center, aims to counteract that neglect and remind its audience of the discarded, forgotten lives behind its iron gates.

Strange Interlude

Strange Interlude, one of four Eugene O’Neill plays to have won a Pulitzer Prize, is brilliant, magisterial, and provocative. How then, does one actor, David Greenspan, take the complex story of Nina Leeds and the four men in her life, a play that is written in nine acts and spans five hours in the telling, and deliver the highs and the lows, the strange twists of fate, the loves, and the schemes of its characters? Dressed in a dapper three-piece suit, Greenspan is alternately Nina, Charles, Ned and Sam (and three minor characters as well), maintaining an energetic, staccato presence while shifting, sometimes with gunfire rapidity, among these characters. Who would have imagined that this 1928 whale of a play could be acted as a one-man show to riveting effect? Greenspan is extraordinary, and he brings to life an extraordinary play.

Occupied Territories

Occupied Territories, a visceral and exciting new play co-written by Nancy Bannon and Mollye Maxner, focuses on two sets of characters separated by 50 years. It begins and ends in the basement of a family home, where Alex (Ciela Elliott) has come with her Aunt Helena (Kelley Rae O’Donnell) to bury her grandfather. They are quickly joined by Alex’s mother, Jude (Bannon), who is recently out of rehab but still in a halfway house. Jude is trying to connect to Alex after what seems to be a series of disappointments her addiction has wrought in the past.

Only You Can Prevent Wildfires

Harrison David Rivers’ play Only You Can Prevent Wildfires takes as its jumping-off point an actual conflagration known as the Hayman fire, the worst blaze in Colorado’s history. Sparked mysteriously on June 8, 2002, the fire burned 137,000 acres and destroyed 133 homes. Fire Prevention Technician Terry Barton later admitted to starting it after burning a letter from her estranged husband. That letter is a focus of several speeches—the play begins with Terry’s insistence that she didn’t read the letter, but rather put it in her purse—yet it’s a mark of Rivers’ skill that by the end of his riveting play one still doesn’t know the contents of it.

Lonely Planet

Jody and Carl, the only characters in Lonely Planet, are habitués of a sleepy little shop called Jody’s Maps in an unnamed American city. These middle-aged men, intricately rendered in Steven Dietz’s subtle, elegiac script, are being realized vividly by New York stage veterans Arnie Burton and Matt McGrath in a Keen Company production celebrating the 25th anniversary of the play’s premiere at Northlight Theatre in Evanston, Ill. Lonely Planet, winner of the PEN Center USA Award for Drama, was written when the arts were being defoliated by an epidemic beyond the American medical community’s control. AIDS is the background of the play, but not its subject.

Measure for Measure

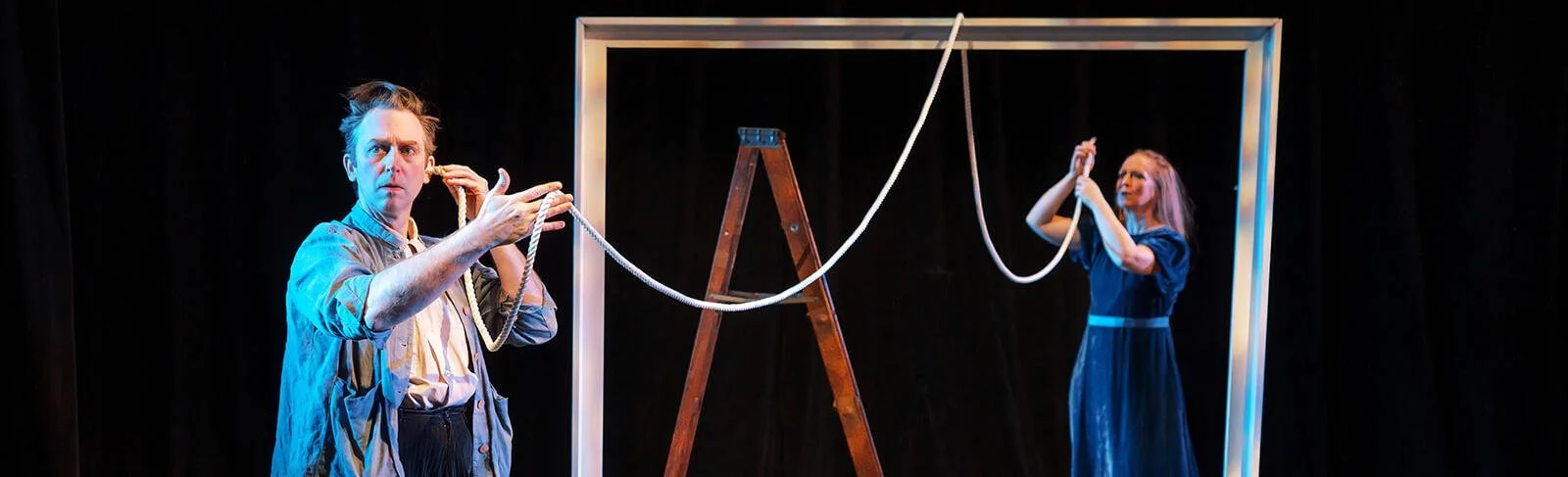

Duke Vincentio of Vienna doesn’t have time to sit and chat. He’s got a dukedom to observe in disguise. “Our haste from hence is of so quick condition,” he says at the start of Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, “that it prefers itself and leaves unquestioned matters of needful value.” Elevator Repair Service’s gaga production of the play at the Public Theater is in as big a hurry as the Duke, but achieves the opposite effect: it tears through the niceties of Shakespeare’s plot only to screech to nearly a full stop in the scenes of highest tension, ensuring that none of the most meaningful fragments of “needful value” passes unheard, if not unfelt.

Tomorrow in the Battle

Curious title, Tomorrow in the Battle. It’s a phrase from Richard III (Act V, scene 3), the partial title of a well-reviewed 1994 novel by Spanish writer Javier Marías, and apparently the English translation of a German war cry. And what it has to do with what’s happening on Ars Nova’s stage, heaven knows. At any rate, to enjoy Kieron Barry’s drama, you’d better love London: there’s a lot of it here. And you’d better have a tolerance for shaky British accents. Patrick Hamilton, as our not-altogether-heroic hero, can’t decide whether to pronounce it “again” or “a gain”; he keeps going back and forth. And Ruth Sullivan and Allison Threadgold, as the women in his life, flatten or broaden their vowels as they see fit, not always consistently.

Tiny Beautiful Things

Tiny Beautiful Things is a curious, only-in-New York beast: adapted by and featuring the screenwriter/star of My Big Fat Greek Wedding (Nia Vardalos), from a collection of advice columns by the acclaimed Wild memoirist (Cheryl Strayed), staged by the director (Thomas Kail) and original producer (Public Theater) of Hamilton. It’s the kind of random concatenation that seems just crazy enough to generate life, but Tiny Beautiful Things is dead on arrival. With its monochromatic script, repetitive staging, and tone-deaf politics, it’s the anti-Hamilton.

Too Heavy for Your Pocket

Too Heavy for Your Pocket, Jiréh Breon Holder’s engrossing new drama, takes place in spring 1961, as busloads of activists, black and white together, are plunging southward from Nashville to Montgomery, Ala., and New Orleans, challenging illegal segregation of public transportation on Interstate highways. Known as the Freedom Riders, the activists are traveling under the auspices of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), organizations crucial to the burgeoning American civil rights movement. Over more than six months, several waves of nonviolent Freedom Riders will subject themselves to varied forms of hostility, from burning crosses and vulgar epithets to life-threatening violence and brutal incarceration, in the hope of effecting social change.

Outside Paducah

Outside Paducah: The Wars at Home, a trio of monologues about the postwar experiences of veterans, focuses on the insurmountable stresses on those who have been emotionally and psychologically scarred by war. Author J.A. Moad II, who has written and performs the plays, is himself a veteran. It is, perhaps, impossible for a civilian who has never endured combat to understand what it’s like, but civilian vs. military mindsets have underpinned plays from Shakespeare’s Coriolanus to David Hare’s Plenty (1978), whose heroine Susan Traherne, after fighting for the French Resistance, thrashes about in an unfulfilling civilian life that can never excite her as much as living on the knife’s edge.

In the Blood

When Suzan-Lori Parks decided to write a play based on The Scarlet Letter, she began with the title: Fucking A. Unimpressed, she deleted everything she had and started from scratch, writing the play that would eventually become In the Blood. As Parks tells it, In the Blood had to come out before Fucking A would crystallize; she calls the plays “twins in the womb of my consciousness.” With both in revival at Signature Theatre, audiences have the chance to view Parks’ twins side by side. The plays are riffs on the theme of our duty to one another, colliding with and speaking to each other in a jazzy feedback loop. If In the Blood ends up the less viable of the pair, it still makes for a fascinating examination of the state the nation from a singular American voice.

Mary Jane

“What’s the matter, Mary Jane?” Alanis Morissette sang in 1995. “You never seem to want to dance anymore.” She could have been singing to the eponymous protagonist of Amy Herzog’s understated new play, who would love to dance, or smoke pot, or hike in the mountains, but all her time and energy are taken up caring for her severely ill 2½-year old son, Alex.

A Clockwork Orange

Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange has developed a life of its own. It doesn’t have the worldwide instant-recognition factor of a Wizard of Oz or a Mickey Mouse, but the opening image of Malcolm McDowell’s Alex deLarge in Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 film is etched in the consciousness of anyone who’s even tangentially encountered the film: chin tucked, eyes leering under the brim of his bowler hat, mouth an inscrutable half-simper, flamboyant fake eyelashes ringing his right eye. No company Halloween party is complete without a Brad or a Dave in deLarge drag. The latest in a long line of theatrical adaptations of A Clockwork Orange, which opened this week at New World Stages, both banks on and challenges this brand awareness, refining the narrative into a piquant, overheated slab of physical theater about the roots of white violence that is part male revue, part alt-rock dream ballet.

Fucking A

Suzan-Lori Parks’s plays always speak their own language, but in 2000’s Fucking A the playwright one-upped herself. The women of the play have developed their own semi-secret language called TALK that allows them to hide in plain sight among callous men. It’s as beautiful and elegant an illustration of female solidarity as any in Parks’s work, and indicative of her gift for fashioning skewed worlds that make us see our own world anew. She doesn’t so much pull back the curtain as shoot it through the back wall.

The Treasurer

“Regarding suicide I just don’t have sad emotions,” says Jacob, the occasional narrator of The Treasurer, Max Posner’s deeply felt, sharply observed play about dementia and care-giving. Jacob (a no-nonsense, resentful Peter Friedman) is the hard-as-nails son who, along with Allen and Jeremy, the more accommodating brothers, must take care of his widowed mother, Ida (Deanna Dunagin, who charts a painfully realistic physical and mental decline). By the play’s end, Jacob is as sad as can be.

Loveless Texas

Inspired by Shakespeare’s Love’s Labor’s Lost, Boomerang Theatre Company’s Loveless Texas is a toe-tapping musical comedy set during the early years of the Great Depression. Although many of the characters hold the same names as in the Shakespeare play, the story begins with a twist: Berowne Loveless Navarre (the hugely talented Joe Joseph) and his buddies—Duke Dumaine (Colin Barkell) and Bubba Longaville (Brett Benowitz)—are playboys who travel from New York to Paris. Along the way they do all the things that upstanding young men shouldn’t be doing: chase women, drink liquor and spend the Navarre family money.

In a Little Room

In a Little Room, a delightful new black comedy by Pete McElligott, co-founder and co-artistic director of the Ten Bones Theatre Company, shows obvious influences of of Albee, Sartre and especially Beckett, but McElligott has his own voice. The play focuses on two primary characters, Manning (Jeb Kreager) and Charlie (Luis-Daniel Morales), who meet in a hospital waiting room on a very bad day. Initially, they try to conduct a whispered conversation to avoid waking another occupant, who is sleeping (David Triacca, who undertakes multiple roles), and then manage to wake him anyway with amusing ineptitude.