Eric Gilde’s new play the goodbye room focuses on a common experience in most everyone’s life—the death of a parent—but more important, it asks the question, “What’s left of the living?” There are those who have to handle the funeral arrangements, travel home for the service, or find a way to relate to one another during a time of grief. It’s the relating that most often gets in the way. Gilde has done an exemplary job of capturing the essence of this experience, and, as the director, creates the space for four talented actors to bring it to life.

It is a detailed re-creation that, without nuanced performances, could easily come off as flat. There is nothing new, there are no great surprises and no profound personal breakthroughs in the goodbye room. However, it’s the precise manner in which Gilde wrote the dialogue, directed the actors, and how they delivered it that enhances the drama.

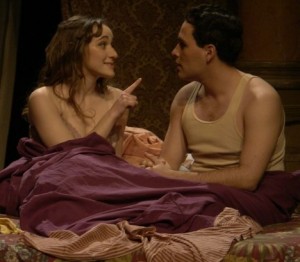

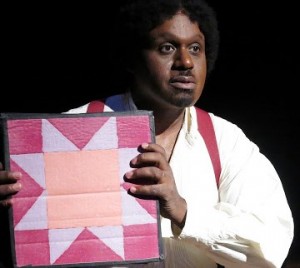

Michael Selkirk plays the grieving Edgar, whose wife has just passed on. Edgar has two daughters—the “good,” overworked, overwhelmed daughter Maggie (Sarah Killough) and complicated Rebecca, affectionately referred to as Bex (Ellen Adair), who married and moved to Chicago five years ago. Bex laments not coming home sooner, while Maggie plays the busy martyr who stayed behind to work and take care of the parents. This sibling story has been told and retold following the death of a parent; however, it’s Gilde’s staccato dialogue, with the characters talking over one another, coupled with the generous space between the words, where the crux is to be found. Included in this drama is the affable family friend and former love interest Sebastian (Craig Wesley Divino.)

Bex is wound tightly, from the moment we hear the car door slam to when she finally tersely reveals, “Larry and I are getting divorced.” The estrangement from her family is exemplified by her awkward attempts to console her father or hug her sister. She often finds a way to make it more about herself than anyone else. Maggie, equally tense, lets on to anyone who will listen how busy and overwhelmed she is. Sebastian has found his second family and doesn’t want to let go, always being available to lend a helping hand. Edgar is trying desperately to understand this new void in his life, even while shuffling off to make coffee or trying make sure his girls are comfortable.

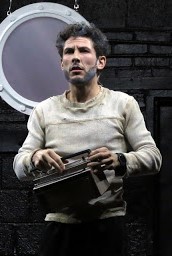

It’s when he shares his Irish whiskey with Sebastian that Selkirk delivers everything that resides just behind the dialogue. “I don’t think you should come around here for awhile,” he says, pausing for a moment, then saying, “Drink up.” The rage that seethes behind his full beard and scraggly appearance is subtle yet profound.

Justin Spurtz’s set covers every base, from the 1950s paint-by-numbers framed art on the wall to the collection of family photos and the paper plates complete with grease stains left behind by the pizza. There is the patterned family sofa that has lost its firmness over the years, and the coatrack filled with winter coats and scarves. Spurtz even includes a bit of whimsy with Bex’s childhood mug.

Jacob Subotnick layers on a sound design that complements each scene, from car doors closing to LPs with crooners on the vintage stereo turntable to the subtle patter of rain. The volume of the mobile-phone ring in the handbag was on point, and the iPod selection set the scene for the sisters to share too much wine, and finally themselves, is perfect.

Gilde’s drama touches slightly on the concept of the lingering spirit of the departed, with lights flickering or the broken stereo finally playing. It’s a welcome relief from the family drama being played out, but it’s also a hint that there is more to life than silly squabbles or playing the blame game one more time. Maybe love, as messy as it can be, transcends the boundaries of this reality to remind us of what’s important.

“The goodbye room” is at the Bridge Theatre at Shetler Studios (244 West 54th St., 12th floor) through March 19. Remaining performances are Wednesdays through Saturdays at 8 p.m. and Sundays at 3 p.m., plus Tuesday, March 15, at 8 p.m. Tickets are $15 and $18 and may be purchased by visiting Artful.ly.