Frederick Douglass said, “Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.” It felt like the spirit of Douglas was downtown at the Gene Frankel Theatre, inspiring all who hear the call to go see Pappy on Da Underground Railroad. This heartrending one-man show, developed by cabaret performer Richard Johnson, under the direction of Keith Allan with musical accompaniment by Terry Wallstein is in honor of Black History Month. Johnson soulfully weaves the tales of trials and tribulations on the trail to freedom with Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad. With honest, down to earth direction and staging, this charming piece found its perfect venue at the Gene Frankel Theatre.

Raw, vulnerable, intuitive, fiery, wise, and out smarting, Pappy is the culmination of all the heroes of that dark time in American history. Soulfully singing some of the old classic spirituals such as “Wade in the Water” and “Steal Away” Johnson, as Pappy, explains how Harriet Tubman used song to guide runaway slaves to freedom. Through Johnson’s characterizations, we learn about the spirit of a people who were willing to pay the price for freedom and how it takes courage and determination to continue to fight for it.

Long-time cabaret performer Johnson authentically brings to life a part of our past that should never be forgotten. In the storytelling tradition of Haley’s Chicken George or Walker’s Celie, without overacted characterization, Johnson shows us the passion of a powerful survivor in his magnetic Pappy. With pathos, he comically impersonates his giggly first love, Mary, who pined for another. He mimics her obsession for, “Jacob! Jacob! Jacob!” and then tenderly reveals she killed herself by drinking lye after her lover was beaten to death for killing the master’s son who raped her. What hits to the core is how Johnson weaves Pappy’s memory with his heart-rending vocal of “Balm in Gilead,” accompanied by the mournful piano rendering of musical director Terry Wallstein.

Johnson’s subtle interpretation of Harriet Tubman is truly inspired. There is never doubt that Pappy is an authority on Tubman. He tells of his first meeting with the sassy Tubman and how she convinces him to come with her on the freedom trail. With hands on his hips, and a molasses sweet voice, he mirrors her command, to go back south to get her mother.

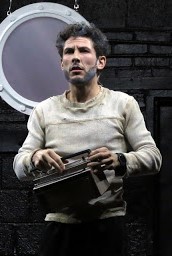

With assistance from technical crew, Stephon Legere, Luis Rivera and Cesar Perez, Allan uses a minimal set, allowing Johnson’s own energy to create the time and place. Small wooden platforms transform from tree stump to safe house cellar doors to a boat on the river, to train tracks to the north. Johnson guides us by the North Star and the sounds and signals along the riverbanks to freedom. The use of haunting sound effects enhances the menace in the moment, further heightening the historical significance of Pappy’s story.

As Johnson sings the doleful spirituals of those times and interweaves the stories of survival and escape to the Promised Land of Canada, he paints a clear picture of those heroes and villains he deals with along the way. Speaking to the audience as if they were his new group of runaways, Johnson creates the suspense and urgency of the time and place in a very internal and organic way, making his audience feel very much the eminent dangers of the ghostly swamps, in the pitch black night.

Perhaps one of the most suspenseful moments was when Johnson transforms into the racist slave hunter and his dog. As the slave hunter reveals his reasons for hating runaway slaves so much—his favorite boyhood mammy was sold off because of her runaway son—the crescendo of his anger rises with the sound of the barking of his dog. This brilliant direction really enhanced the danger of that moment in the journey to freedom.

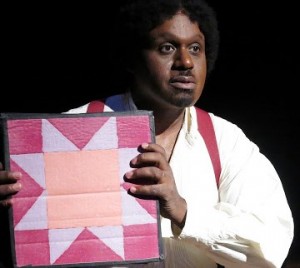

Johnson really draws in his audience as his partners on the Underground Trail. When Johnson illuminates on the hidden meanings of the railroad terms, he also sheds light on how significant the building of the railroads were to the emancipation of slaves. Sitting comfortably Indian style, Pappy decodes the meaning of the symbols of the quilts and reveals the ingenuity and sophistication of a people intend on gaining freedom. With the eerie sounds of the river flowing in sync with Johnson’s rich vocalization of the classic, “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” he elucidates on how each symbol will be signs along the way to guide his motley runaways to safety in Canaan, which Pappy declares is the name for Canada. On reaching the Promised Land of Freedom, Pappy leaves us with a sense of hope for the future, as long as we never forget those champions of the past.

In these tumultuous times, Johnson’s exploration of the past is very significant. It encourages us to be as brave and determined as people like Harriet Tubman and all the unsung heroes of that time. In order to change history, we must learn from it. Johnson, in his poignant characterization of Pappy, leaves us with the great message that the heroes of yesterday can inspire the heroes of tomorrow. As Alice Walker said, “Harriet Tubman was not our great-grandmother for nothing.”

Pappy on Da Underground Railroad's last performance was Feb. 27 at the Gene Frankel Theatre (24 Bond St. between Bowery and Lafayette St.) in Manhattan. For more information, visit brownpapertickets.com.