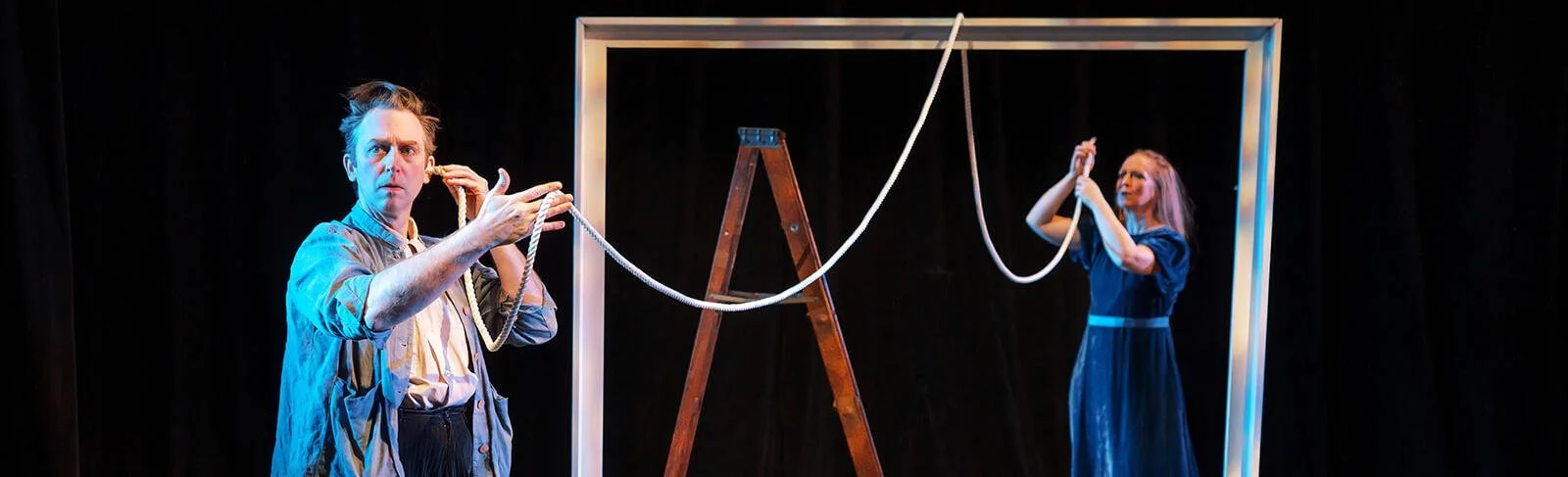

In Robert Lyons’ Death of the Liberal Class, directed by Jerry Heymann at the New Ohio Theatre, Nick, played with a self-deprecating aplomb by Steven Rattazzi, is a balding, pot-bellied academic who has written a book called "Robo Corp" that has garnered him great success after years of being an adjunct professor and a freelance journalist. However, after a “nervous breakdown” in which he rejects the ideas he has written about in the book—that robots will take over the world and that they are “standing on the precipice of the darkest period in history”—he has retreated to a farmhouse in Canada owned by his wife’s family.

His teenage daughter Andrea, played with a convincing mixture of indifference and righteousness by Jeanette Dilone, however, has dropped out of high school and followed him there. She has swallowed her father’s previous convictions hook, line and sinker, and has decided to pursue her own brand of activism, “hacktivism.” She is joined by the unassuming yet handsome Even, played by Justin Colon (who appears to have a magnificent singing voice revealed in one small snippet in the play) whom she has met online. The computer is the perfect tool for activism. Where it was once dangerous and possible to suffer bodily harm—think Kent State University in 1970 when four were killed and nine wounded in a melee between protesters and National Guard—computers have removed the physical component of activism and provided the safety of anonymity. Even and Andrea quietly, heads together, plan to take down the Robot Economy that her father has written about. The sexual tension is palpable even with their eyes glued to their respective keyboards.

Meanwhile, everyone is mad at Nick. He’s been sleeping with Maggie, the dewy skinned and wholesomely pretty Olivia Horton, who lives on the farm next door with her husband, and also with Daphne, his wife, when she comes to visit. Maggie’s husband beats her for sleeping with Nick and Daphne chides him for leaving New York City.

Although there is still sexual chemistry between them, Melissa Murray as Daphne captures the understated disdain that New Yorkers have for those who leave. After all, who, in their right mind, would leave an Upper West Side apartment in New York City? She may as well come out and say it: he’s a loser! But, somehow, living on the farm, in the middle of Canada has made Nick feel peaceful, and dare we say it, happy. In the opening scene, Nick’s daughter notes how happy he seems. When he retorts “I’m not allowed to be happy?,” she nearly chokes with disgust, “Not this happy!”

Nobody wants Nick to change, especially his daughter. Yet, he no longer believes in the chaotic world he wrote about in his book nor does he want to have anything to do with it. His daughter decides to carry out her own grassroots activism, and hacks into Maggie’s account. Comic relief comes unexpectedly in an exchange between Nick, his daughter, and Constable La Fontaine, a Canadian Mountie who works in the cyber division, played with wonderful restraint by the mustachioed Arthur Aulisi. When the Constable arrives at the farmhouse to investigate the hacking, they deny it. Although the Constable remains beautifully polite, it appears he knows better. It’s a moment filled with tension and irony.

Although we usually think of men as being better hackers, Andrea is actually the gifted hacker who plans to infect Wall Street computers with a virus that will bring them crashing down. Nick pleads with her, and asks her to see how it will affect the little people, but she is so full of her own—or rather Nick’s—ideological idealism that she runs off with Even to carry out the plan.

When Nick’s wife realizes he isn’t coming back to the city with her, she leaves and gives him an eviction notice from the farmhouse. In the beginning of the play, you wonder what Nick’s appeal is: he’s a middle-aged guy with thinning hair and a thickening middle who’s sleeping with two beautiful women. But then we see that it’s his underlying sensuality that makes him attractive. After he rejects his own lofty “liberal” ideas about the Robot Economy, he actually becomes more attuned to the world of living through the senses. At one point, his daughter comes to him, computer attached to her arm like an extra appendage, complaining she can’t get access. He gently says “access these trees… access the sky.”

Robert Lyons’ play asserts a very important message in this age of technology: that it can be both useful and destructive, but what it’s not, is sensual. Nick may be the underdog here, but in the end, he’s the one who is the true activist: being in tune with the senses is more likely to save humanity than anything else. The rest of the world around him needs a little more time to get there.

Death of the Liberal Class, written by Robert Lyons and directed by Jerry Heymann, runs through Feb. 13 at the New Ohio Theater (154 Christopher St., #1E between Greenwich and Washington Sts.) in Manhattan. Performances are Wednesday–Thursday at 7 p.m., Friday–Saturday at 8 p.m. and Sunday at 5 p.m. Tickets are $18 and can be purchased by calling 1-888-596-1027 or visiting http://www.NewOhioTheatre.org.