The Birds, Conor McPherson’s creepy new play, is derived neither from Aristophanes nor Alfred Hitchcock. It does, however, share DNA with the 1963 film because both draw from a short story by Daphne du Maurier. (Hitchcock also used du Maurier novels as source material for Jamaica Inn and his Oscar-winning Rebecca.) Don’t expect to find real birds or even simulated ones in the pocket drama at 59E59 Theaters. Fans of the movie won’t find a pompous female ornithologist with environmental concerns or a schoolteacher with her eyes pecked out either.

That Pharmaceutical Connection

The drug that gives Ana Nogueira’s new play its name, Empathitrax, fosters complete intimacy between two people in a relationship. The users take it with water, then wait a bit and touch each other—waves of empathy ensue as the feelings of the other become utterly accessible. It’s apparent almost immediately that the man and woman in Empathitrax—Nogueira’s script identifies them only as Him and Her—need artificial stimulation. As they meet with a delivery guy from Empath in their minimalist living room to discuss dosages and procedures, they interrupt themselves, grasp at each other awkwardly, smile uncomfortably and generally broadcast that their relationship is strong but that there might be some problems.

Nogueira develops her theme carefully. Focusing on a drug that interferes with one’s natural personality traits is not a fresh topic—Placebo and The Effect have been there—but Nogueira’s play is still a strong entry in a subgenre of modern drama. It allows its actors to work with a wide range of emotions. And those actors—Jimmi Simpson and Justine Lupe as Him and Her, and Genesis Oliver, who doubles as the Empath delivery man and as Him’s buddy Matty D.—give astonishingly good performances, not just charting the emotions unleashed by the drug, but investing the science-fiction aspect of the story with credibility. As they undergo the effects of Empathitrax, they touch each other and each feels what the other is feeling. The physical empathy they enact is persuasive and overpowering.

Simpson once starred on Broadway in The Farnsworth Invention and looked set to be a fixture in the theater, but forsook it for television work. He was clearly an actor of great gifts, and they have not diminished. He uses every second of stage time, much like Vanessa Redgrave, to create a pointillist portrait. One is afraid to look away for fear of missing the tiniest apt grimace, deep breath, or shoulder shift that conveys crucial information.

If Him is calm, rational, giving and patient with his partner to a fault in their daily lives, Her can still push his buttons at times. She buys a bed they cannot afford without consulting him, and that provokes exasperation. But every interaction, every hesitation, every flash of emotion between Simpson and Lupe is precisely evoked under Adrienne Campbell-Holt’s superb direction.

Lupe’s Her is needy and insecure, and although the opening scene with the delivery man plays like a Cowardian comedy of manners, things turn darker. “This play is a comedy, until it’s not,” reads a direction in the script. And it’s quite funny for awhile, as Him subsequently meets with his buddy Matty on the rooftop to vape and describe his experience with the drug. “I guess that I didn’t know how much the little things mattered to her and she, she didn’t realize just how much I cared about her,” he says. “But now we can actually show each other, transfer the information. It’s quick and it’s potent.”

Matty tries to relate every emotion to a past drug experience: “So it’s like doing Molly?” he asks. “So like, a Xanax.” He’s an expert on artificial stimulants, but, in a scene at a party with Her, he reveals that his impetus to using drugs may well be a result of his sick father: “He’s like, almost catatonic, all the shit they have him on. It’s keeping him alive which is good, I guess. But.” To which Her responds: “But what’s the point of being alive if you aren’t really taking it all in.”

It’s a modern dilemma—the desire to experience everything. Even the rampaging use of the Internet to see life in all corners of the earth, to miss nothing, to signpost one’s existence for others to notice, is a symptom. Her tries to finesse the shortcomings of her relationship with him by adopting a dog, Rufus, who is kept in a crate and sometimes barks and sometimes is heard chewing on treats (the sound design is by Matt Otto). Rufus’s unconditional love cheers her, and Lupe has a couple monologues with the dog, in which she displays her neediness: “Do you like me even a little? Do you realize I saved your life? No one in the world knows what could have happened to you if you stayed in that shelter.”

In Nogueira’s satisfying ending, well grounded but still a surprise, the author comes down on the side of natural experience rather than chemically induced effects. Simpson’s Him does something uncharacteristic—he improvises—and the delicacy and romance of the final moments pull the play back from the darkness enveloping it. It’s no longer a comedy gone awry.

Colt Coeur's production of Empathitrax plays at HERE Arts Center (145 Sixth Ave., entrance on Dominick Street) through Oct. 1. Evening performances are at 8:30 p.m. Thursday through Saturday, and 7 p.m. Sundays and on Monday, Sept. 26. There is also a matinee at 4 p.m. on Oct. 1. Tickets are $18 and may be purchased by visiting here.org.

Cracking Open

In Honor Molloy's Crackskull Row, a hovel in Dublin becomes the unlikely setting for an emotionally overwrought, Oedipal drama. The play is set in 1999, but it has the audience fooled—Molloy's play has all the trappings of a mid-20th-century, Joycean family narrative. Although the audience often hears references to staples of modern life—mobile phones, an ESB (Electricity Supply Board) company, even Oxfam—they sound anachronistic against this landscape of aged, mournful nostalgia. But for all its old-world charm, Molloy's riveting words don't translate perfectly to the stage. Directed by a courageous Kira Simring and staged by the cell at the Workshop Theatre, this beautifully written, hauntingly poetic story struggles to find the right tongues for its finely crafted words.

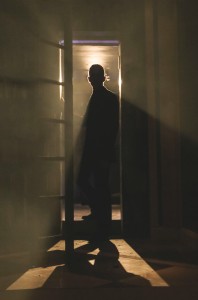

The production opens with the dour throb of a drum and that sprightly music so unique to the Irish musical tradition. An old man named Rasher/Basher, played by Colin Lane, enters, a lone figure with light streaming around him, and says that the sound we hear is "the thrum of the bodhran." It is a kind of Irish drum, well-known for its dooming, thumping sound. He talks wearily, anxiously, about his past, saying that his 'Da' was a musician, and that, although he's been away from home for 33 years, he's become the "spit and shite" of his father's likeness. A sense of foreboding takes hold, the rhythm of the bodhran notwithstanding. Then we see the ramshackle insides of a Dublin home. A vast, untidy sofa, wooden walls with peeling plaster, and a film of dirt covering the kitchen all clue us into the premise of Crackskull Row: a home has been leveled by the passage of time but seems ripe for renewed activity.

What follows is a disturbing but absorbing puzzle about Rasher Moorigan (John Charles McLaughlin), his father Basher (Lane, who also plays the older Rasher), mother Masher (Terry Donnelly) and daughter Dolly (Gina Costigan). Masher is almost literally rotting inside her electricity-less, plumbing-less home on Crackskull Row, her bills from the ESB piling up on the sofa. And while her past bothers her terribly, she is saved by the remembrance of her son, Rasher, and the sustenance of her daughter, Dolly. But it's soon apparent that the narrator, an aged Rasher, himself is unreliable, as are one's eyes and ears. Personae are fluid; the four players inhabit other bodies, take on different accents, and change their clothes easily. Suffice it to say that Rasher and Masher Moorigan are hiding a lethal, 30-year-old secret, the reverberations of which are still knocking around in their battered skulls.

There is much to admire about the production, including some fine performances from John Charles McLaughlin, who plays a young, on-edge, perversely romantic Rasher, and Gina Costigan, whose Dolly is a complex, willful thing. But their enthusiasm doesn't quite make up for the uneasy adaptation from script to stage. Crackskull Row often values dramatic potential over clarity, and while some climactic, intimate scenes (like Rasher's interactions with Dolly, or the dying moments of the play) are intensely dramatic, others fall into a spasmodic mode of meaningless activity. The result is not just an abrogation of Molloy's authorial intent for Crackskull Row, but a confusingly paced, occasionally overwrought performance.

Save for a few rare scenes of sparkling chemistry, the production threatens to come away at the seams. Molloy's dialogue is chock-full of intelligent wordplay, quick humor, and wit, but combined with the Irish brogue and quick delivery, her words (when delivered on stage) take a while to register. As a result, the enjoyment of the play is temporarily stunted. Much of the magic that can be read in Molloy's teasing, metaphorical writing is either difficult to find or nonexistent in the staging. We happen upon the wordplay, or a throwaway malapropism, a little too late to derive a complete appreciation of the story.

Yet, the production is redeemed and revived by its flowing, narrative core, and the actors who bring it to life. The chemistry between McLaughlin and Costigan is palpable; it's not for nothing that the Masher-Rasher relationship is central to the play. Lane brings a nostalgic weariness to his role, and lends a dreamy gravitas to the production. But it is Costigan who bears much of Molloy's light-hearted darkness from the page to the stage; she plays Dolly with riveting, minimalist understanding. Even her mirror, Terry Donnelly's Masher, does not waste a single movement (although words seem to be held in lower regard). To help us forget this latter discourtesy, M. Florian Staab (responsible for all the original music and sound design) punctuates scene changes with welcome percussion and fiddle-song. In moments of stillness or silence, there is Daniel Geggatt’s set to appreciate, in blue, brown and yellow, seeming for all intents and purposes like a living thing. As for the other living things taking the stage, they—and the playwright—are among the only reasons you should take a trip to the Workshop Theater this week.

The cell's production of Crackskull Row runs through Sept. 25. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Thursday through Saturday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. There are additional performances at 7 p.m. on Sept. 14 and 21. The Main Stage of the Workshop Theatre is at 312 West 36th St. (between Eighth and Ninth avenues). Tickets are $25. For more information about the show and tickets, visit www.thecelltheatre.org.

When Women Burn

The visual imagery presented in The Flea's The Trojan Women strikes two seemingly disparate chords upon viewing. One is of The Rape of the Sabine Women, an ancient Roman story about soldiers who arrived on the shores of Italy. The men abducted and otherwise ravished a group of Sabine women. Another image, more overt (and one we are asked to leave the theater with), is the violent uprooting of millions of Syrian refugees from their homes. As Hecuba, Helen, Andromache and Cassandra bitterly mourn their fallen city, we cannot help but think of their lives in a foreign, hostile country, as they are carried off in boats that are almost as precarious as their hollow futures.

This resonance, sometimes obvious and sometimes thrillingly unspoken, is the beating heart of this drama, written by the silver-tongued Ellen McLaughlin. Enveloping this drama, which has survived well past its antiquarian origins, is the tragic, antediluvian helplessness of postwar women at the hands of their conquerors. It is the human tension of the play, with its mostly female cast, that rings through McLaughlin's words and lifts the story into beautiful, complex territories. Directed by Anne Cecelia Haney and under the much-lauded artistic directorship of Niegel Smith, this adaptation of Euripides' antebellum narrative, if occasionally flighty, is moving and cinematic in its scope.

The play begins with the drugged monotone of waves crashing against a beach, as we are welcomed into The Flea's downstairs theater. It seats perhaps forty—the intimacy of the space threatens our bubble of suspended disbelief. As if painted onto the wall, a turbaned, blindfolded woman sits, waiting. On the floor lie some six women—this is the Chorus—curled up and covered in grey blankets. The music of the sea gradually bestirs the blindfolded woman, and from her commanding voice and gait, we gather that she is Hecuba (played by a marvelous DeAnna Supplee), former queen of Troy and war prize for the Greeks. The women of Troy have been captured by their enemies the Greeks following the sack of Troy, and are waiting to be shipped off to kings' courts as slaves, concubines or second wives—harder luck perhaps than their Sabine ancestors. Cassandra (a powerful Lindsley Howard) and Andromache (Casey Wortmann, wonderful) are among the most haunted: the former has been 'made mad' by the god Apollo for spurning his love, and the latter is the widow of Hector, a fallen Trojan prince. All are violently helpless and burning with war trauma, with nothing to do but wait.

Haney has expertly interpreted McLaughlin's words, which retain most of the flair and poetry of Euripides' original. As the Trojan women dream of their future lives, they repeat stories of far off countries: "If you wash your hair in their rivers," one of them says, "they come out gold." Haney builds particular emphasis around this optimism, for it is mirrored in the current refugee crisis that has shaken the world with its sorrow. Here is where McLaughlin, who first adapted the story with the Bosnian war and its aftermath in mind, becomes fickle: the plot is held together by the barest of backbones, and for all the characters' elegies and monologues, there are times when the postwar narrative seems too forced, too distant. But when we are reminded, it is powerful: doctors, engineers and artists leave behind their burning cities for lives as taxi drivers, postmen and even unemployment, just as Hecuba, Andromache, and their once regal companions become less than their former selves. They resign themselves to lives of physical and emotional imprisonment.

Hecuba embodies all the nostalgia, mad sorrow and pride of her fallen Trojan citizens. Supplee delivers the fallen queen's lines with wounded ferocity; even when she whispers, there is weight and regality behind it. Tears shine perpetually in Hecuba's eyes—her only equal is Helen (Rebeca Rad), played with a great deal more pathos and wit than the original character is intended to have. In the 1971 film, starring the luminescent Vanessa Redgrave and Katharine Hepburn as Andromache and Hecuba respectively, Helen is a teasing, dangerous, one-dimensional male fantasy (both ancient playwright and seventies era director were male, after all). Rad anneals this fantasy with humanity; her lines are the most moving ones McLaughlin has written in the play.

The entrance of a male soldier, Talthybius (Phil Feldman) towards the end spins the play into a climax. Suffice it to say, he is dressed in combat gear and bears bad news for the women, just as they have seemingly reconciled themselves to their futures. In happier moments, the play has spontaneous moments of song and dance, welcome augmentations to the narrative. Lighting and sound design (Scot Gianelli and Ben Vigus respectively) are both characters of their own, booming and crackling with emotion as the play progresses. Both are also responsible for the cinematic sweep of the concluding scenes, perhaps some of the best minutes of The Trojan Women. Come for the nostalgia and the instructive, present performances, but stay for those dying moments.

The Trojan Women runs through Sept. 26. Performances are Thursday through Saturday at 9 p.m. and Sunday at 3 p.m. Tickets are $15-$20 with the lowest priced tickets available on a first-come, first-served basis. The Flea Theater is located at 41 White St. between Church St. and Broadway. Purchase tickets by calling 212-352-3101 or visit theflea.org.

Order in the House

Are all plays that are lost and recovered theatrical treasures? At first, A Day by the Sea, the Mint Theater’s production of a neglected 1953 play by British dramatist N.C. Hunter, suggests the answer is no. However, under Austin Pendleton’s steady and gentle direction, we gradually see how effectively Hunter scratches the surface of social interactions to reveal what lies beneath: sadness, anger, and disappointments, as well as hopes and dreams. As the play opens, Julian Anson (Julian Elfer), a civil servant living in Paris, has come for a visit to see his mother at the family’s seaside estate. He doesn’t really want to stay. He barely sits down, and when offered a lawn chair, appears extremely uncomfortable in Elfer’s fine characterization. He captures Julian’s physical and social awkwardness. His stooped posture and pinched face communicate frustration, and his body seems to lean toward the exit, like he’s yearning to make a quick escape.

Julian’s mother, Elinor Anson (Jill Tanner), has been keeping up the estate, but she is particularly frustrated by Julian’s lack of interest in the villa, and also by her aging uncle, David Anson (George Morfogen), who seems about to expire. Morfogen brings the right combination of lethargy and energy to the role, showing both a doddering elder and someone who’s not quite ready to give up on life. Elinor frets over the household expenses, part of which go to alcohol consumed by David’s live-in caretaker, Doctor Farley (Philip Goodwin), who often launches into dark, despairing tangents. Julian’s response is “the drinking isn’t dangerous, just boring.” Additionally, there is the estate’s accountant, William Gregson (Curzon Dobell), who also seems to be in limbo.

A group of visitors is also in the mix. Frances Farrar (Katie Firth), who is staying at the villa with her children while she disentangles herself from a marriage, has been away for 20 years. She was raised by Elinor, along with Julian, after she was orphaned. Though hardly scandalous today, in the period of the play divorce is talked about with a hushed air. Frances is what might be called a “hot mess.”

Another “hot mess” is the nanny, Miss Mathiesen (Polly McKie) who, at 35, has never been married, but has her eye on the doctor. The actual day of Hunter’s title occurs in the second act (of three), and it brings forth the tensions that lead to Julian’s recognition of his stiflingly rigid life. Elinor insists he join the family for the outing, which forces him to meet his boss, Humphrey Caldwell (Sean Gormley), at the beach, where Caldwell delivers unpleasant news. At first Julian’s reaction is angry and impulsive: he uncharacteristically climbs a cliff to retrieve a lost kite for one of France’s two children. Climbing the cliff, retrieving the kite, and tearing his trousers—all seem to loosen him up, and he becomes more candid and open.

A Day by the Sea initially seems like a play of manners. Hunter and his fellow playwrights (Noel Coward among them) were replaced in the 1950s by “the angry young men,” a group of writers who focused on the working class and their struggles living in postwar Britain, still reeling from the devastation of World War II. Plays like John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger and Harold Pinter’s The Birthday Party presented human nature in a cynical way and had characters who were cruel and self-serving as they scrambled to survive.

Although Hunter’s play is not raw like those of Pinter and Osborne, it’s not Disney either—not everyone lives happily ever after. Instead, it shows how much we really just march through life. Expert lighting by Xavier Pierce and the sets by Charles Morgan suggest the ease and comfort of an English seaside villa, but they don’t undermine the fact that personal revolutions are often frustrating, fraught with despair, and don't always lead to the expected outcome. In the end Julian tries to make sense of it all but finds no simple answers. He looks out at the vista and talks about possibly transforming the landscape to get a better view of the sea. His mother, who has done nothing but goad and chastise him for not being more successful as a civil servant, is clearly happy that he might stick around a little longer. And why not? What more perfect setting to contemplate life?

The Mint Theater production of A Day by the Sea runs through Oct. 23 at the Beckett Theater (410 West 42nd St. between Ninth and Dyer avenues). Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2:30 p.m. Saturday and Sunday, with a special matinee on Wednesday, Sept. 21. Tickets are $57 and may be purchased online at Telecharge.com, by phone at 212-239-6200 or in person at the Theatre Row box office. For more information, visit minttheater.org.

Is It a Crime?

Director Whitney Aronson’s approach to August Strindberg’s rarely produced Crimes and Crimes is to streamline and bring out the dark comedy that the play encompasses. Her adaptation of the Swedish playwright’s work has been updated to present-day New York City. She has taken the attitude that the realism and harsh events that occur in the original version undermine the notion of it as a comedy. For her adaptation, she says in a note, she wanted the audience to see and understand Strindberg’s play. Aronson’s version begins with Jean (Ivette Dumeng) and her show dog Maid Marian (played by actress Katie Ostrowski), a Hungarian sheepdog, frolicking in the park, enjoying their time as they wait for Jean’s husband, Maurice (Randall Rodriguez). Emile, Jean’s brother, later joins them, and they discuss Jean’s concern that Maurice is planning to leave her. (Aronson doesn’t explain why these residents of New York should have French names.)

Jean is afraid that she will not be able to afford Maid Marian’s dog show expenses if Maurice divorces her. Emile and Jean speak of how Maurice, an author, rarely takes her on his book tours or to social affairs. She tells Emile, “I don’t know, but I have a feeling that something dreadful is in store for me.” Suddenly Maurice appears and begins caressing Maid Marian, whom he clearly loves. He also gives the impression that he loves Jean and enjoys her company and physicality. In fact, he invites her to the opening of one of his plays and she refuses. She tells him she will be better at home with Maid Marian. They part ways, and the play begins to unfold the “something dreadful” that Jean fears.

Maurice goes off to meet and start an affair with Henriette (Christina Toth), who is in a lesbian relationship with his close friend (a man plays the friend in Strindberg’s original). The tension increases: Maurice must now decide if he stays with his wife or goes with his new lover. As he contemplates his decision and how difficult it would be to see Maid Marian if he divorces Jean, the dog mysteriously dies.

One of Aronson’s most radical changes to Strindberg’s original text is that Maid Marian is a replacement for the mistress’s daughter. She writes that she made this choice because she wanted the play to be more believable: “I actually did it because in the original, the child dies and nobody really cares.”

Although there’s a logic behind Aronson’s choice, it may not resonate with the same intensity as Strindberg’s. “I thought that the audience would not be able to forgive anyone in the play for so easily moving on from the death of a human child. A treasured animal’s death, though tragic and upsetting, is more consistent with the general reaction and behavior that Strindberg’s characters demonstrate.”

But even though the change from child to animal does lighten the mood and makes Maurice’s actions somewhat more forgivable, some of the plot stretches credibility. After the dog’s death, animal law enforcement appears to investigate the crime. As serious a crime as animal abuse is, it seems rather fantastical that a Broadway-type play would be pulled because of animal abuse. In any case, Maurice is charged as the main suspect, but he is eventually exonerated. Within hours of his release, Maurice’s reputation is ruined, and his play is pulled.

Whether the choice to change the daughter to a sheepdog is fully justified or not, it does not take away from the lightness of the play. It does, however, make the circumstance melodramatic and absurd, which brings out the humor in the play.

Matthew Hampton and Holly Albrach’s costuming of the characters is impeccable: fashionable and in line with the current New York scene. They employ an approach to the Hungarian sheepdog that seems to draw inspiration from puppet theater. It was entertaining and just simply delightful to the eye.

The sound design by Andy Evan Cohen makes the transition between scenes lively, using instrumentals of popular pop songs. They are played with a classical twist, so the audience is left to try and identify the familiar tune.

Aronson has accomplished her goal. The play has witty moments and comic scenes. The absurdism makes for great melodramatic humor as well. The revision keeps the audience focused on its entertaining and engaging story for the entire duration.

Crimes and Crimes plays through Aug. 20 at the Gene Frankel Theatre, 24 Bond St., in Manhattan. For tickets, call (212) 868-4444 or visit www.strindbergrep.com.

A Family’s New Chapter

An Ecuadorian father, Nelson (Anthony Ruiz), struggles to reconnect with his three adult children when his past catches up with him in Vanessa Verduga’s comedy Implications of Cohabitation. Verduga also plays the love child, Sara, who does not relate to her half-siblings, Kevin (Andres de Vengoechea) and Jenny (Connie Saltzman). Their father, Nelson, had an affair with Sara’s mother, Carmen (Adriana Sananes), when she worked as a waitress at a local Ecuadorian restaurant. Sara is a successful attorney with corporate clients, yet she is insecure when it comes to relationships with men. Kevin is an actor, but his father wants him to run the family construction business. Jenny is a punk rock singer who smokes marijuana and is still finding herself. Nelson’s wife, Caitlin, and mother to his two children, Kevin and Jenny, has recently passed away. Now alone, Nelson decides to live with each of his three children in their separate homes with the hope that they will take care of him in his old age. Nelson soon realizes that his children are more concerned about their own lives, and they are not interested in being his caretaker.

The comical misunderstandings throughout this production are amusing, as when Nelson discovers Jenny’s bong, but the humor cannot hide the lack of believability that pops up. In the beginning, when Kevin and Jenny share that they are still grieving over their mother’s death, there are not any memorable, somber moments to express their sadness or loss. They are more focused on viewing their half-sibling, Sara, as an outsider. Sara has a distant relationship with Nelson, while Kevin and Jenny seem to be closer to him.

It does not make sense that Nelson did not first ask his children if he could live with them. It suggests that Nelson has not been around his children for some time now, and he suddenly wants to spend his life with them. When Nelson does show up on their doorsteps, his children are so lost in their own worlds that they do not know what to do with him.

Right before Nelson arrives at Sara’s apartment, Sara’s ex-boyfriend, Jake (James Padric), a gay boxer, staggers into Sarah’s living room drunk. Jake says, “I fucked up. Me and Jean got into a huge argument. And now he’s disappeared.” Jean is Jake’s boyfriend, and Jake goes on about how worried he is about Jean. Padric’s entrance is confusing and it is a stretch to buy that Jake has genuine feelings for Jean and is actually worried about him. Padric does eventually pull off his character splendidly, with physical humor and succinct comedic timing when he mistakenly overdoses on the anti-inflammatory drug Naproxen.

Later, Nelson meets an alcoholic homeless man (David Pendleton) at a bench in a park. The two men get acquainted and eventually Nelson offers the homeless man a beer as they chat. Pendleton was giving a stellar performance until, unfortunately, he forgot his lines and whispered this to Nelson. Fortunately, Ruiz didn’t flinch and continued with his lines until he exited. His accomplished performance from the moment he appears on stage really holds this show together.

Set designer Anna Grigo creates a neat and organized set with a park on the left, an apartment in the middle, and an Ecuadorian restaurant on the right. What does not work is that the apartment is static and does not transform enough to represent each of the children’s homes. The transitions are also noticeably long. A picture is simply replaced on the wall to represent that the set has changed from Sara’s to Kevin’s apartment. When it is supposed to be Jenny’s apartment, some clothes are thrown on the furniture. The interior decorating best suits Sara’s taste and temperament, and it is easily plausible that this is her home. Kevin does not seem successful enough as an actor to afford to live in such a place. Jenny appears more like a squatter or an Airbnb guest in this space.

Even with a two-act structure, Implications of Cohabitation never fully ripens to the point where Nelson is actually living with any of his children. The play gradually takes a turn and focuses more on Sara’s wedding and the participation of her friends and family members. There is probably a great wealth of material that could be further explored by having Nelson live with his children. When telling a family story between two disconnected generations, it can be fascinating to watch how both generations play off of each other’s differences. Director Leni Mendez’s challenge is to bring greater authenticity to this production through natural performances and maintaining the original intention of this story.

Implications of Cohabitation runs until Aug. 26 at the Clurman Theatre (Theatre Row, 410 West 42 St., between 9th and 10th avenues) in Manhattan. Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday and at 7 p.m. on Aug. 23. Tickets cost $20.25. To purchase tickets, call 212-239-6200 or visit sudacastheater.com.

A Civic Jewel—and Free!

There is something appropriate about offering Shakespeare for free in the parks of New York City. Like the great rivers and mountains of the earth or the stars and planetary system—which charge no admission for us to admire them—Shakespeare is a force of Nature that belongs to us all.

Artistic Director Stephen Burdman has made it the mission of the New York Classical Theatre to bring free Shakespeare productions to various parks during the summer: following this year’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the late romance The Winter’s Tale, brilliantly conceived, acted, and deeply moving, to boot.

The Winter’s Tale, first performed 405 years ago in 1611, is about the fallout of a king’s jealousy when the ruler, Leontes, wrongly imagines that his devoted wife, Hermione, has consorted with his best friend, King Polixenes, and that the child she is to bear him is not his. Only after the death of Leontes’ young son and sole heir, Mamillius (Peyton Lusk is delightful in the role), followed by the death of his faithful queen, does the king awaken from his madness and see his foul crimes for what they are.

Here is a feast of self-deception, delusion and jealousy for Shakespeare to plumb in all of the pity and horror his majestic language can inspire before the play resolves, after an improbable leap of 16 years in time, on happier notes: the reunion of the two friends, Leontes and Polixenes; the forthcoming marriage of their children, Florizel and Perdita; and most ridiculously wondrous of all, the revelation that the statue of the long-dead queen is really a living and breathing Hermione, now returned to the bosom of her husband and family. If the question is whether or to what extent a particular performance of The Winter’s Tale allows the audience to utterly suspend their disbelief when confronted by such leaps in time and “happy” endings, the production did very well indeed.

Brad Fraizer in his beautifully acted role as Leontes carries the emotional sweep of the play from his increasingly insane jealousy to the extremes and horror of recognition of his crimes, and from there to the reconciliations wrought by Time and Chance. It is a challenging role.

David Heron as his beloved childhood friend, King Polixenes, is commanding and passionate in his role. Hermione, so profoundly wronged by her husband, is portrayed by Mairin Lee with a queenly elegance, dignity and sensitivity. Mark August, who plays the clown, Autolycus, is extraordinary and deserves special mention for his comic brilliance and gifts. So, too, does the stirring performance of Lisa Tharp as Paulina, maid in waiting to the Queen, whose impassioned rebuke to Leontes for his treatment of his wife is heart-piercing. For all of the loveliness of the outdoor setting, it also places special demands in clearly projecting Shakespeare’s language, to which the cast rose magnificently.

As the play moves from Act II to Act III, the audience also moves—from Clinton Castle (Leontes’ court in Sicilia) to a lawn overlooking the Hudson River (the shores of Bohemia). Burdman calls this his “panoramic” technique, a method by which the audience is less a witness to the actions before it than at the center of those actions. It is as if the viewers were really accompanying the courtier Antigonus, sent by the mad Leontes to abandon his own newborn daughter, Perdita. Over the Hudson, just in front of the audience, is a real cloud-flecked sky with real birdsong mixing with the sounds of the city in the background. Scene iii of the next act takes place on a different lawn (another location in Bohemia) to which the actors, again, lead the audience. The scene is one of a sheep shearing and, as evening gathers, the audience sits amid trees and grass exactly as they might at a real sheep shearing.

In Burdman’s “panoramic” approach, the entire park is our stage. There are no sets. Scenes are acted in different areas of the park with the audience sitting on the ground or grass, and the staff, in the first row of the audience, shining flashlights on the characters once it has become dark. Shakespeare’s language and his dramatic exploration of human character and heart fill the entirety of the space with no theatrical paraphernalia to draw off attention. And the effect is simply stunning, as less proves so much more! There is no lovelier way to spend an evening than to allow Shakespeare’s magic to sizzle and cast a net over you and over the city itself.

Meet outside Castle Clinton in Battery Park at 7 p.m. nightly (except Thursdays) through Aug. 7 (via 1 train to South Ferry or the 4/5 to Bowling Green). The Winter’s Tale will then move to Brooklyn Bridge Park from Aug. 9-14 (take F train to York, 2/3 to Clark or A/C to High), also at 7 p.m. There will be no performance on Aug. 11.

A Midsummer’s Nightmare

Luckily for dramatist Elda Cusick, the director of her new play, Austin, A Summer Night's Dream in Hell's Kitchen, hired very good actors; they are the saving grace for a rambling and extremely shopworn script. It is truly unfortunate that Cusick’s muddled drama has wasted such talent.

The playwright purports to tell the story of the title character, a middle-aged, recovering addict (Thomas G. Waites), who returns to his family after his seventh stint in rehab. Austin surprises his wife, Petra (Rochelle Boström), and teenage daughter, Dory (Michaela Waites), who are living in Brooklyn. However, he is staying with his brother Martin (James McAffrey) in their childhood brownstone in Hell’s Kitchen.

In rehab Austin has had a relationship with one of the therapists, Andy (AJ Cedeño), who uses gardening as rehabilitation tool. Juxtaposed to this unethical patient/therapist behavior, Dory complains to her mother that her therapist is touching her inappropriately. Petra brushes off the concern with, “That’s called ‘therapeutic touch,’ to comfort you,” but quickly follows it with “You could dress more modestly.”

Austin is riddled with narratives, most which are poorly thought out. Every character is conflicted, and it’s no surprise that Cusick uses the name Pandora for the daughter (“Dory” for short). The only common, if entirely preposterous, theme, is that Austin believes he will return to his wife and daughter. Andy chastises him about his sexual ambivalence: “There’s a lot of guys like you, your age bracket, having problems like you’re having.” Meanwhile, Andy suffers from his own internal conflict and attempts to kiss Dory. Later, Dory admits to her uncle, Martin, who has been having an affair with her mother for years, that she has been having sex with a number of men: François, Pascal, a deli guy, a mechanic, and a policeman, to name a few. She’s pregnant but, shockingly, doesn’t know who is the father.

Whether Austin the play, not the man, could be fixed is entirely questionable. Cusick’s script has a deep distrust of therapists, which is prevalent throughout, and she does not appear to have an understanding of addiction or rehab. With information so readily accessible on the Internet, her lack of knowledge regarding science or the basic concept of linear time is even more striking.

The absurdities are startlingly apparent in a scene in which Dory reminds her mother of the time that she “put the thermometer in the pea soup on the stove to get a high temperature so I wouldn’t have to go to school” and that it broke in the soup, which they subsequently ate. The fact they all survived drinking mercury, when even a minuscule amount is lethal, is utterly confounding—not to mention that nobody noticed the glass in the soup.

Director Ed Setrakian’s staging for the most part is passable. However, he hasn’t helped the writer clear up some of the clumsy storylines, and much of the blame for the play’s failure belongs to him. Set changes are cumbersome and lengthy, and the rooftop scene at the end is played on a high upper level. In the scene Austin finally learns of his wife’s affair with his brother and confronts Marty. They fight, but it loses all impact by the sheer distance from the audience. The hashed and rehashed story of the gay or lesbian dying a tragic death is dated and, frankly, offensive. More so with the additional details that Martin, at the behest of their father, beat his brother brutally when they were children because Austin was thought to be a sissy.

Life may be this messy, but Austin comes off as a ripoff of a film noir interspersed with narratives from a cheap romance novel. Cusick provides little for the audience to latch on to, with themes that are trapped in a time warp. Sadly, even with the quality of the actors, there isn’t a character worth caring about.

Austin continues through Sept. 9 at The Lion Theatre (410 W. 42nd St., between 9th and 10th avenues). Evening performances are Wednesday through Saturday at 8 p.m.; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $59.50 and available by calling Telecharge at (212) 239-6200 or (800) 432-7250 or visiting Telecharge.com.

(Un)Happy Family

Tolstoy said: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The origins of unhappiness are certainly a unique combination for every family. For the one in Ann Adams’s Strange Country, directed by Jay Stull at the Access Theater, mental illness, lack of loyalty, and addiction are the sources that lead to complications between siblings.

The play opens on a one-room efficiency apartment: beer cans, leftover foods and trash are strewn everywhere. The occupant, Darryl (Sidney Williams), is fast asleep on the couch, until his sister, Tiffany (Vanessa Vache), lets herself in. After she puts food in the refrigerator, she assesses the situation and wakes him up by spraying him with Fabreze. Roused from his sleep, Darryl cries: “That shit will give you cancer!” The irony of the line is not lost on Tiffany. Darryl is a slob who seems completely unconcerned with his personal hygiene, the cleanliness of his apartment, or his health. He even confesses that he medicates himself on a steady stream of beer and meds.

Tiffany gently tosses back an ironic barb of her own: “Maybe you’ll eat your dinner one day, rather than drink it.” As Tiffany bangs around the apartment trying to clean up, she orders her brother to go wash up so they can go to their mother’s re-commitment ceremony. This brings on a stalemate.

Tiffany seems abrasive and angry, but underneath her volatile outbursts and no-nonsense demeanor is a woman who really cares about her family. If she didn’t care so much, she wouldn’t spend her morning goading Darryl and trying to do what’s best for her family. This concern extends to her girlfriend, Jamie (Bethany Geraghty), who is stony-faced and avoids eye contact with Darryl. She seems highly displeased with the situation.

At one point in the play, which moves along organically even though the dialogue is a bit stultified in places, Darryl and Jamie find themselves alone in Darryl’s apartment. Darryl is thrilled to discover they are both trying to move forward while simultaneously being moored by addiction. He practically whoops: “You’re the first person who’s made me feel good about myself” and “You’re more fucked-up than me!”

While Tiffany tries hard to keep the family together, Darryl steadily consumes beer. As he opens one can after another, the sound of the initial pop of the tab, and then the fizz of the beer become a soundtrack for his character. Nonetheless, Darryl is like the idiot savant, or the fool in Shakespeare’s plays. For all his slovenly drunkenness, he has wisdom and insight. He’s right on when he says plaintively to Tiffany: “The whole of your life is trying to fix people who don’t want to be fixed. But you cling to it.” He knows her life’s purpose is to stay close to her family and try to keep them together, but he can’t help and doesn’t want to.

Strange Country does a good job of capturing the sadness that is brought on when a family member is suffering from a problem that is too difficult to fix. However, it also explores the complicated idea that what may be good for one person may not be good for another. Everyone has his own way of surviving, and the measures people use may not always be the right ones. For Darryl, this is his way of surviving; it’s his “normal.” Tiffany has another “normal,” a more conventional and socially acceptable one. But she doesn’t seem happy. Although Darryl seems less productive and more destructive, he seems more content with his life and himself. It’s a philosophical conundrum.

Strange Country by Anne Adams, produced by New Light Theater Project, runs until Aug. 13 at 8 p.m. Wednesday–Saturdays at Access Theater(380 Broadway at White Street, in Tribeca). Tickets are $15 in advance, $18 at the door, and can be purchased online at: http://www.newlighttheaterproject.com.

Wounds That Won’t Heal

The works of Northern Ireland playwright Owen McCafferty may be unfamiliar to regular theatergoers in America, but since the early years of this century he has been building an important body of work—a visit to London in 2002 brought this writer in contact with Closing Time, an early play with the inestimable Jim Norton. Hosting a production from the Abbey Theater of McCafferty’s Quietly, the Irish Rep is doing a service by introducing the playwright, even if the work at hand has its drawbacks.

The acting isn’t one of them. From the moment he enters, the shaved-headed Patrick O’Kane’s Jimmy is clearly a “hard man,” one that you wouldn’t want to face down in a bar, where McCafferty has set his story of confrontation and reckoning. Jimmy is tense, simmering with anger and radiating danger as he offers the bartender, Robert (Robert Zawadzki), his services in running off wild young teens gathering nearby. It’s the night of a soccer match between Poland and Northern Ireland—the play is set in Belfast in 2009—and Poland is Robert’s native country. “Do you want me to go out and get rid of them?” Jimmy asks, and Robert answers, “They’re only kids.” Jimmy responds, “Kids can do more damage than you think”—a deft foreshadowing of what’s to come.

Jimmy Fay’s production is splendidly designed by Alyson Cummins, though perhaps a bit too gleaming to be a rundown pub, improbably empty on the night of a major soccer showdown. Except for Jimmy, Robert, and the Ian of Declan Conlon—clad in a black leather jacket and no less imposing than Jimmy, even with a graying beard—nobody is in the bar watching the television match.

The connection between Jimmy and Ian goes back to their boyhoods, and one instinctively knows—and it’s shortly apparent—that their enmity dates from “the Troubles” and the height of civil strife between Protestants and Catholics in Northern Ireland in the 1970s.

McCafferty’s play focuses on the wrongs each side perpetrated on the other during the 1960s and ’70s—particularly in that same pub, on a night in 1974 when Poland also played Northern Ireland (a little too conveniently, perhaps)—and the damage inflicted on the country’s children, as well as the necessity of letting go of the past. McCafferty’s plot may be particular to that conflict, but his template is familiar from dozens of other plays. Nor, indeed, after an early moment of sudden violence, does one expect any more, for the longer the men talk, the clearer it becomes that there’s dirty laundry to be aired but that some form of nonviolent resolution will take place rather than more blood spilled.

Jimmy’s anger dates from a bombing in the same Belfast bar on a crucial night in 1974. Six men were killed, one of them Jimmy’s father, but the repercussions have scarred both Ian and Jimmy. The talking that ensues, fueled by alcohol, of course, peels back layer upon layer of each man’s history, and Fay punctuates the dialogue with long, awkward silences that thicken the atmosphere with tension.

Still, it’s hard not to feel that the story may carry more weight for McCafferty and an Irish audience that it does for a foreign one that didn’t experience the strife decades ago. The analogous situation might be for a New Yorker and a bin Laden follower involved in 9/11 to meet in a bar, with the lesson that both must let go of the past, but that’s not likely, and there’s a whiff of unearned optimism in the ability of these men to abandon revenge in lieu of understanding. Still, McCafferty settles on a note of ambiguity to end Quietly, a moment that deftly suggests danger is unpredictable and never far away.

The Abbey Theatre production of Owen McCafferty’s Quietly, presented by the Irish Repertory Theatre and the Public Theater, runs through Sept. 11 at the Irish Rep (132 W. 22nd St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday and Thursday and at 8 p.m. Wednesday, Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 3 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. Tickets may be purchased by calling OvationTix at (212) 727-2737 or visiting irishrep.org.

A Paradise for Paranoia

You are locked inside the small lobby of a corporate office building with 10 other strangers. An ominous voice on an intercom informs your group that you have one hour to escape. The lights go out. A screen flickers on, flashing random surreal images quicker than your brain can process. A human eye; a girl in a forest; a Romantic painting; an architectural spiral. Everyone panics.

This might sound like a nightmare, but it's actually the beginning of Paradiso Chapter 1, a self-described immersive theatrical escape room experience located in Korea Town. Created by theatrical innovator Michael Counts, Paradiso tries to set itself apart from other New York City escape rooms by incorporating several rooms of immersive theater, live actors, and "existential themes." Despite these claims, however, Paradiso does not escape the genre of escape rooms, which is limited by design.

Originating in the early 2000s, escape rooms have gained popularity in many cities across the world, especially in Asia and the U.S. In New York alone, there are dozens of escape rooms to choose from. The concept is simple, but the design can be very complicated: groups of participants are put inside a room or series of rooms and must solve a gauntlet of puzzles within a set time in order to "escape." Many of these rooms have themes. Paradiso Chapter 1 seems to evoke corporate corruption similar to dystopian film and TV shows like Mr. Robot or V for Vendetta, with scattered references to Dante's Divine Comedy.

The Paradiso experience begins days in advance with a series of cryptic text instructions sent to your personal cell phone. A few hours before, you are instructed to meet at an obscure karaoke bar in K-Town. While this messaging system seemed to work for some participants, for one technical reason or another, several others did not receive correspondence. A set of email instructions advice participants to surrender all of their belongings to storage before the experience, but no such check was mandated (only offered to participants who wanted to shed their bags). This meant that, for better or for worse, our group relied on our cell phones throughout the experience—for illumination, notes, or recording clues or images.

During the experience, actors appear to help or hinder your quest to escape. Sarah Jun, Claire Sanderson, Joe Laureiro, and Brian Alford all manage to develop interesting characters within the confines of the escape room format. It is unclear exactly what is at stake, but it seems as if Virgil Corporation is trying to cover up some secrets hidden within their commercial empire. It is left ambiguous whether any of the characters are sympathetic to Virgil Corporation, or whether they are sincerely trying to help you escape. With such a talented cast at hand, Paradiso might consider developing a clearer storyline and incorporating each actor further into the fabric of the experience, perhaps to develop a storyline and to offer insight into the show's supposed existential themes. Instead, the actors felt more like fancy props, limited to (with the exception of Jun) garbled utterances about clues.

Escape rooms, by nature, are different every time. One may or may not escape, depending on the speed at which their group finds and interprets clues correctly. Paradiso claims to incorporate immersive theater techniques, but do not expect the same level of detail as the exquisitely designed sets of companies like Punchdrunk or Third Rail. These immersive companies take precise care to make sure that every object within the interactive set tells a story. The objects in Paradiso seem more haphazard. Additionally, many immersive theater productions, such as Tony & Tina's Wedding, allow participants to talk to the characters and piece together a narrative through their interactions. However, do not expect to interact meaningfully with the characters as one might in local immersive productions such as Speakeasy Dollhouse or The Grand Paradise Hotel.

Escape rooms are not for everyone, but if you enjoy high-pressure gaming environments, definitely attend Paradiso: Chapter 1. Be aware that the pace is fast, the energy is high, and the rooms can become very hot. If immersive and interactive theater is more your thing, consider skipping this one. Our group was unsuccessful in escaping, and Alford's character booted us to the curb as quickly as Jun's had swept us in. Despite failing, it was a unique experience, and will definitely get your adrenaline going.

The open-ended run of Paradiso: Chapter 1 plays Wednesday–Friday from 6–9:30 p.m., Saturday from 2–9.30 p.m., and Sunday from 2–8:30 p.m., with audiences entering every half hour. Paradiso: Chapter 1 takes place at a secret location in Korea Town that is not unveiled until audiences arrive at a designated meeting point shared when their tickets are booked. Tickets start at $45 and are available via www.paradisoescape.com. Advance booking is required.

The General Takes a Stand

Richard Strand’s Butler leaps to the forefront of comedies set during the Civil War—although it may well be the only comedy set in the Civil War that comes to one’s mind. Yet the setting is indubitable, and the laughs are plentiful, so if it stands alone in a genre of one, it doesn’t matter. The only drawback will be if it spawns a spate of Civil War comedies that prove inferior.

The four-character play, directed by Joseph Discher, takes place in a small general’s office at Fort Monroe, Va., at a crucial juncture—Virginia has seceded from the union the day before. The general, only recently been put in command, is Benjamin Franklin Butler, an irascible, sometimes pompous Union officer. He is attended by a Lt. Kelly, a strapping subordinate whose manner is by turns unyielding and abashed in the face of Butler.

As the play begins, Kelly has unwelcome news for Butler: “There is a Negro slave outside who is demanding to speak with you.” A scene ensues in which Butler berates Kelly for a number of reasons, including choices of words: “demands” vs. “requests,” “surprised” vs. “astonished.” The scene is labored and makes one fear that the play isn’t going anywhere soon, but bear with it: these language debates pay off richly in the second half.

In Ames Adamson’s performance, Butler puts on a lot of bluster. He’s chafing in his new post, because he knows he doesn't have the background of other generals—he was a lawyer in civilian life not so long ago—and because he suspects that Benjamin Sterling’s Kelly, a graduate of the military academy at West Point, resents being under his command. Yet, as the plot unfolds, Adamson shows an unexpected tolerance in the character, and Butler’s acceptance that he must stand up against the orders of President Lincoln, the Cabinet and all the generals superior to him. It is a precarious position, because the war has begun and the Army of the Confederacy is all around.

The Negro slave, Shepard Mallory (John G. Williams), seeks asylum at Fort Monroe, but Lincoln’s policy requires all fugitive slaves to be returned to their owners in the South because they are escaped property. Strand touches briefly but vividly on the horrors of slavery, as Mallory shows the scars on his back, but the meat of the play is the debate between general and slave about asylum. As in many classic comedies, the servant is a shrewd cookie, and Williams charts Mallory’s course of defiance and submission as he plays off Butler’s expectations. The character is insufferable at times, sympathetic at others, and Williams’s skillful performance keeps the right balance. (The production is from the New Jersey Repertory Company, and it’s heartening to be reminded of the high quality of regional theater.)

Strand brings Act I to a strong climax, as Mallory warns Butler about the man who is coming to retrieve him and take him back to a certain death at the hands of his cruel master. In Act II, the emissary, Major Cary (David Sitler), enters blindfolded (Steve Beckel’s sound design provides some delicious laughs in the moments leading to Cary’s entrance). The scene that follows is worthy of Shakespeare, as Butler summons his lawyerly skill to find a loophole to deny Cary his repossession of Mallory—which the historical Butler did. The scene is reminiscent of Portia’s springing the trap with “Tarry a little, Jew” in The Merchant of Venice.

Although the sparring between Butler and Mallory is the main event, the two supporting players are equally good. Sterling charts Kelly’s course from a man who has no experience of Negroes, and no interest in them, to one who finds a conscience and joins Butler and Mallory for a brotherhood-of-man finale. As the representative of the South, Sitler’s Cary is suitably arrogant and unlikable, and gets what he deserves.

A strong, satisfying comedy that worked no less well last summer with a different cast at Barrington Stage in the Berkshires, Butler makes one want to hear more from Richard Strand.

The New Jersey Repertory Company’s production of Butler plays at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St., between Park and Madison) through Aug. 28. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday through Thursday and 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday. Matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. For tickets, call Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200 or visit 59e59.org.

Revolutionary Relations

A powerful and thought-provoking drama, A Man Like You tells the story of a British diplomat abducted by Somali terrorists and held for ransom for months. Throughout the work, Kenyan-born playwright Silvia Cassini addresses one overarching question: What constitutes terrorism? The piece chillingly delves into a world ravaged by colonization, the plight of the Somalis, radicalization, Islam, the current political scene, and what exactly so many so-called legitimate governments do in the name of democracy and thinly veiled corporate interests. Very little is being referenced in the media about Somalia beyond piracy. A Man Like You is a play to be experienced.

The vast majority of the fast-paced and intricate dialogue, against the backdrop of a distraught wife, is between Patrick North (Matthew Stannah) and his abductor, Abdi (Jeffrey Marc). Andrew Clarke plays a Somali rebel guard.

Director Yudelka Heyer heightens the emotional and often violent physical relationship between North and Abdi. By design, the tension is palpable from the moment North, hooded and gagged, is thrown into the cell and chained to a metal cot. Taunted by his captor, North eventually acquiesces to what seems like his abductors’ only demand—that he sign a letter replacing a company that has been preferred for a government contract, but not after challenging them: “You really expect me to believe that all this is just to remove a single individual who some warlord ‘dislikes’?” If this were the only reason for his abduction, life would be simple, and A Man Like You is not simple.

It is wrenching and skillfully presented, with acting that is complete and detailed. The audience is on two sides of the stage and in some cases sitting at stage level. The smartly designed set, by Christopher Wharton, bifurcates the stage with a windowless cell at the front closest to the audience; behind it, slightly raised, is the living room of the North’s home in Nairobi.

Credit is due Cassini for what must have been exhaustive research, resulting in a script that is as tightly crafted as a century-old Berber carpet. The argumentative dialogue details the plight of the Somalis through decades of colonization, and it becomes clear that they are just pawns in a greater political and well-funded chess game.

Heyer is from the Dominican Republic, a country with its own history of strife and political upheaval. As director, she helps Stannah and Marc deliver a knockout punch that drives their performances to the edge of sanity. They, along with Clarke, realistically play the strongly staged fight scenes. Interjected as counterpoint to the scenes in the cell are the monologues of North’s wife, Elizabeth (Jenny Boote). Boote brings a calculated, reserved British air to her nuanced performance as North’s clearly distraught wife.

Much has been written about the American Revolution rejecting the control of Britain and the monarchy. No doubt the conversation in Britain was about the terrorists commonly referred to as “the colonies,” while on this side of the pond it was considered a revolution. Using the conflict in Somalia as the canvas, A Man Like You rips apart the oft-used language we are quick to label terrorism.

Performances of A Man Like You, presented by RED Soil Productions, are at 8 p.m. Wednesdays-Saturdays and at 3 p.m. Sundays through July 31 at IATI Theater (64 East 4th St., Manhattan). Tickets are $30 and may be purchased by calling (800) 838-3006 or visiting BrownPaperTickets.com.

’Shroom Relief

Desperation courses through Adam Strauss’s performance in The Mushroom Cure. The solo show, which he has written and stars in, details his battle with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and his attempts to find help. It’s a serious subject: the illness preys on the mind of its victims, allowing them no assurance that what they’re doing at any given moment is the right thing. It keeps them on a psychological yo-yo, and can impair their ability to form lasting relationships. Yet Strauss, a stand-up comedian, tells his story with humor as well, as the best playwrights do for serious material. (The piece won an Overall Excellence Award for Solo Performance at the New York Fringe Festival.)

The Mushroom Cureis structured as a series of scenes, with Strauss playing varying characters. Sometimes Strauss is the host, sitting on a vermilion swivel chair and speaking to us about his drug dealer, Slo. The chair also serves as office furniture when Strauss seeks help from a bizarre psychotherapist who turns out to have post-traumatic stress disorder. (A scene when they meet for a session in Tompkins Square Park is very funny.)

Strauss is becomingly ordinary, with his mop of black hair itself displaying some disorder, but less than his personality provides. He works up the courage to speak to a pretty young woman named Grace in a bar. She’s from Kansas, and he envisions her as innocent and not quite beautiful but acceptable. His waffling is a subtle indicator of the OCD at a mild stage. In any case, they have a one-night stand, and he finds he wants to see more of her, but she has only been visiting New York and is leaving for California. Stepping out of the present, Adam speaks of the ex-girlfriend Annie who left him, and reveals that Grace is the first woman who has slept over since Annie.

His relationship with Grace leads Strauss to search ever more desperately for biochemical relief for his disorder. He has already read about psilocybin mushrooms in a psychiatric journal—Grace is conveniently also studying medicine, and supports him. The article relates that some people have found their OCD entirely eliminated after the mushroom cure, so he has tried to order them through his marijuana dealer, Slo. But mushrooms are nowhere to be had; there’s a shortage.

Strauss then embarks on a series of other cures. He tries strange white powders ordered from China, and they arrive in plastic bags coded with numbers and letters. As each new avenue opens up, he gets jumpier and more fraught with anxiety.

In his search for relief, Strauss also tries cacti, as he and Grace get out of the city to a sojourn on Martha’s Vineyard, in a segment that’s particularly evocative and poetic. They see shrimp larvae misting in the moonlight by the shore. But Strauss’s OCD still has hold of him, and Grace’s patience with it seems unending. Until she can’t do it anymore.

Under the direction of Jonathan Libman, Strauss does a splendid job of navigating romance, pain, desperation, and humor in the piece. (During the press performance I attended, however, Strauss broke character to ask a woman in the front row not to scribble notes; it was a stunning breach of theatrical protocol, but given the history he was pouring forth, it was understandable. He did his best to incorporate the episode as a joke later on and alleviate the writer’s discomfort.)

Ultimately, Strauss acquires the psilocybin mushrooms and returns to Martha’s Vineyard alone, in the winter, to try them out. (The playwright in him carefully indicates the passage of time.) The experiment skirts a near-disaster, and brings him a measure of relief. That’s surely why the actor/playwright is donating all profits from the show to the Multidisciplinary Association of Psychedelic Studies (MAPS). It is the nonprofit behind the study that caught his eye.

Adam Strauss’s The Mushroom Cure is playing at the Cherry Lane Theater (38 Commerce Street, three blocks south of Christopher Street) through August 13. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday and 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday. Matinees are Sunday at 2 p.m. Tickets may be ordered by calling OvationTix at (866) 811-4111 or visiting themushroomcure.com.

Sliding into Darkness

The play has been lauded as one of the best English-language examples of the German experience during the Nazi regime. It follows the life of John Halder (Michael Kaye), a professor devoted to his wife (Valerie Leonard) and children who falls in love with a student (Caitlin Rose Duffy). His elderly mother (Judith Chaffee), who can no longer see and suffers from neurotic breakdowns, is institutionalized in a health care facility. She laments often, “What have I got to live for?” Halder has been so moved by her experience that he has written a book on compassionate euthanasia that has caught the attention of the Nazis.

Halder succumbs to the praise the Nazis have foisted on him. Though one of Halder’s best friends is Maurice (Tim Spears,) a Jewish analyst who is well aware of the coming dangers and hopes to get his family to Switzerland, Halder continually tries to reassure him, stating, “...all that anti-Jewish rubbish. Just balloons they throw up in the air to distract the masses.” They use his writings and his work at the university to pressure him to lead a book burning, which he does, asking if he can keep his books.

An underlying popular musical theme provides Halder an Everyman appeal as he shrugs off the propaganda as a passing fad. A longing to belong and the middle-aged man’s desire to avoid his family obligations round out the character. Whatever core beliefs Halder has held are overshadowed by the sheer power of the Nazi machine and the propaganda— “Deutschland Über Alles.”

The overall set design is inventive yet simple—wooden boxes of different sizes that are thrust together or pulled apart to create seating, along with an upright piano that is used to house props. Both are employed by Petosa to create the height, movement, and tension appropriate to the play. The palette for the costumes by Jessica Vankempen seems appropriate for late-1930s Germany. Only the lighting by Hallie Zieselman is problematic. It could be that she is at odds with the house trading off curtain times with the PTP/NYC production of Howard Barker's No End of Blame, but the lighting is sketchy, too often leaves the actors in the dark, and feels like an afterthought.

Frankly, the great challenge for director Jim Petosa’s heart-wrenching revival is the backdrop of politics 2016. The vitriol used to deliver misogyny, xenophobia, and homophobia among so many other divisive tactics being employed by politicians and pundits today makes this play almost pale by comparison. In Good, the horrors of Nazi Germany can be felt in Petosa’s direction of Kristallnacht, with so many good people standing aside. The question is, Can mankind learn?

C. P. Taylor’s Good runs through Aug. 6 at The Atlantic Stage 2, on 16th Street between Eighth and Ninth Avenues. Evening performances are 7 p.m. Tuesdays through Sundays; matinees are at 2 p.m. Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays. Good runs in repertory with No End of Blame by Howard Barker; for exact days and times, visit PTPNYC.org. Tickets are $35, $20 for students and seniors and may be purchased by calling 1-866-811-4111 or online at PTPNYC.org.

Out of the Past

First-time playwright Mat Schaffer is fortunate to have Brian Murray in the cast of his play Simon Says. Murray lends gravitas to the story of a “channeler”—emphatically not a medium, according to Murray’s character, Professor Williston—who connects to an entity named Simon. It’s been a while since the estimable Murray had a good part, and one wishes he were able to lift Schaffer’s serious-minded play beyond fiddle-faddle, but it just gets talkier and sillier in spite of the talented performers.

Williston, who has been the guardian of a young man named James since his childhood. James (Anthony J. Goes) has extraordinary paranormal powers as a channeler; but his mother exploited his renown until he had a meltdown during a tour, whereupon she abandoned him in Las Vegas. Williston then took guardianship. James has been lying low since that time, but the unscrupulous—or perhaps just blinkered—Williston wants to pursue James’s powers in the name of science and a book he has written. To do so, Williston has himself diverted funds for the overdue college education that James desperately wants in favor of their pursuing a money-making tour for the book. His plans change, however, upon the arrival of a young woman named Annie Roberts.

Annie has arrived for a channeling. She wants to contact her dead husband, Jake, who was killed in a car accident in the Berkshires that she survived. Strangely, the letter requesting this particular date was never opened by Williston, who nonetheless has expected her. Though James refuses to channel Simon for her, he ultimately relents.

Under Myriam Cyr’s direction, one’s disbelief may be suspended for awhile, and there’s certainly a frisson of creepiness when James, following the first channeling, says that he still hears Simon’s voice and a sudden, unexpected transformation occurs. Before you know it, poor James’s corporeal being has become Grand Central Terminal for spirits who are far from blithe, including Simon. Though Simon is known to Williston as a being who has existed through centuries and been “a priest at Luxor, a concubine in the Han dynasty,” the ancient shades go back to the Essenes, an early Christian sect to which Simon belonged that is best-known for the Dead Sea Scrolls. In addition to the sought-after Jake, the Essene intruders pop up in Williston’s cramped and book-strewn study (nicely realized by scenic designer Janie Howland).

From then on, the story of Judean love and betrayal is one that perhaps only Shirley MacLaine could buy whole hog. More notable than the direction is John R. Malinowski’s snappy lighting: it works overtime, changing with each new inhabitant’s arrival and departure, until you may find yourself admiring the light show more than the story.

Schaffer leaves it unclear whether a belief in the paranormal is the central issue or whether it’s reincarnation. Both are invoked as the bodies on stage become repositories for the insubstantial spirits, and though to some extent they can be related, the two prongs here overwhelm a story that needs more credibility.

Murray is blustery and gimlet-eyed as the sneaky Williston, and it’s pleasant to see him indulge in his formidable gift for comedy. Sitting under a teardrop glass lamp, he describes to Vanessa Britting’s Annie the division of labor: “He and I work as a team,” says Williston. Lightly flicking his fingers at a potted fern, he adds, “I create the ambiance.”

Goes is an effective and sympathetic James—working-class, sweaty and desperate to find his freedom from his past. One senses his yearning for independence, and Goes throws himself into the physical aspects, falling kerplop in and out of trances. Britting is a lovely and sympathetic Annie, although her hysteria at recounting her husband’s death is a bit over the top. As the catalyst for the evening’s revelations, however, she serves admirably.

The play is diverting, though one’s pleasure may depend more on individual thresholds of disbelief. For people with scant interest in credibility and a high tolerance for mumbo-jumbo, its romance-novel message of love surviving across millennia may be just the ticket.

Simon Says plays at the Lynn Redgrave Theater (45 Bleecker St., between Bowery and Lafayette) through July 30. Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday. For tickets, call OvationTix at (866) 811-4111 or visit simonsaystheplay.weebly.com.

Liberty for All

Liberty: A Monumental New Musical captures an America not unlike the one we see today: a place where people want to come, but also where many struggle to find work and build a simple but stable life. The story begins when Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, a French artist, lovingly completes his statue and sends her to the United States (it's a gift from France to commemorate a century of independence), as if she were his own child. Liberty (played by teenage actress Abigail Shapiro) comes looking for a pedestal on which she can stand to spread her message of hope and freedom.

However, when she arrives at Ellis Island, she is given the same treatment as every other immigrant. She is poked and prodded, and given the twice-over; only to be rejected—after all, what is her purpose here anyway? Hope? That’s not enough. Commissioner Francis A. Walker, who was responsible for the census in the mid-1800s (played with a debonair charm by Brandon Andrus), schedules her to return to France on the next boat. Liberty perseveres. After all, hope is not only for the immigrant, but for everyone seeking freedom and a better life.

The wonderful cast brings life to a variety of characters: an Italian immigrant (Nick Devito), an Irish foreman (Mark Aldrich, who also plays news mogul Joseph Pulitzer), a Russian knish seller (Tina Stafford, who moves gracefully between the Russian Olga, and a wealthy American heiress named Regina Schuyler), a former slave (C. Mingo Lingo), and a native American Indian (Ryan Duncan).

Liberty is a love song to New York—a city that embraces everyone, or at least tries to—but it’s also a history lesson. There’s a great deal of information about Emma Lazarus, played with tight-lipped determination by Emma Rosenthal, who is the most well-drawn character in the play, and the most interesting. She teaches English to Giovanni, an Italian immigrant who seems to hang around the port (is he being deported, or just a loafer?). His improved English increases his betting options: “Ten to one!” he says triumphantly and skitters off. Emma looks after him with a wry smile, clearly amused. This intrigue, however, is forbidden: Emma is from an affluent Jewish family that has been in America for four generations. Hanging around the port and new immigrants is not what a society girl is supposed to do, even if she is a poet, and Regina Schuyler, a wealthy woman who puts her money where it will give her the highest profile, makes sure Emma knows she’s being watched.

With book and lyrics by Dana Leslie Goldstein, there are some laughs along the way. Particularly funny are “The Charity Tango” sung by Liberty, Commissioner Walker and Schuyler, and “We Had It Worse” in which the Russian immigrant Olga and the Irish immigrant Patrick McKay compete to see who had it worse when they first arrived in America. However, as they crescendo in their comparisons, they also discover they agree on something when they sing: “Kids have no idea what hard work is” (…) “Soft” (…) “like a boiled cabbage,” and do a double-take in each other’s direction; they finish the song with a broad smile.

The production is fun, and kid-friendly, but very uneven. While the libretto is outstanding, the music by Jon Goldstein sounds canned; all the tracks seem to have been created on a synthesizer. The stage also feels small, not only because it is small, but because Evan Pappas's staging lacks dynamics and, at times, deflates the production. Some choreographed movement would have given the actors some breadth and depth and the production real musical-theater flair. Nonetheless, the cast clearly has their musical theater chops, and is led to a hopeful finale by Lady Liberty, who proves that perseverance pays off—a message we know is often true.

Liberty: A Monumental New Musical plays an open run at 42 West, 514 West 42nd St., between 10th and 11th avenues. Performances are Sundays at 2 and 5 p.m.; Mondays and Wednesdays at 3 and 7 p.m.; and Thursdays at noon and 3 p.m. Tickets are $72/$36 (premium/child premium); $63 (adult); $27 (children 4-12) and may be purchased by visiting LibertyTheMusical.com.

Hats for Free!

It’s rare to see anything remotely like Torry Bend’s The Paper Hat Game: a seamless and brilliant performance collage of live puppets, small-scale set models, a variety of video modalities, intricate soundscape, and more. The delicacy, virtuosity, and utter freshness of this avant-garde theater work at the 3LD Art & Technology Center will delight you long after you’ve left the theater. Unselfconsciously Dada, surrealist, naturalist and psychodrama by turns, it is also none of those things: something utterly new.

A Heartsong for Hades

Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown, a concept album turned folk opera, adapts the myth of Orpheus by infusing it with American folk and New Orleans jazz music. Now playing at New York Theatre Workshop, Hadestown follows Orpheus (Damon Daunno) to hell and back again in pursuit of his young lover, Eurydice (Nabiyah Be), who has been lured there by the lord of the underworld, Hades (Patrick Page). Being a “folk opera,” the production is almost entirely sung-through, and Rachel Chavkin’s direction carries one song fluidly into the next. Like its classical source, Hadestown is alternatively gorgeous and dark, and the heartfelt commitment of the cast and musical ensemble brings the myth’s paradoxically sad beauty into full bloom.

As an energetic balance of hope and sadness, Hadestown finds light in the darkness and vice versa. The production’s casting reflects this balance: the naiveté of Be’s Eurydice and Daunno’s Orpheus contrasts starkly with the underworldly knowingness of Amber Gray’s Persephone and Chris Sullivan’s Hermes. Sullivan’s portrayal of his character is particularly complicated, as an enlisted messenger for the underworld with a soft heart for the young lovers. The Fates (played by Jessie Shelton, Shaina Taub, and Lulu Fall) are similarly uncommitted in their alliances, singing at times of great love and at others of shattering despair. As the brooding, unrelenting Hades, Page’s reverberating bass vocals figuratively open the doors of hell itself. In voice and movement, this hugely talented ensemble strikes near-perfect harmony in Act I. Act II contains major strengths, including some of the show’s most tear-jerking moments, but overall it lacks the simpatico energy of Act I.