Director Whitney Aronson’s approach to August Strindberg’s rarely produced Crimes and Crimes is to streamline and bring out the dark comedy that the play encompasses. Her adaptation of the Swedish playwright’s work has been updated to present-day New York City. She has taken the attitude that the realism and harsh events that occur in the original version undermine the notion of it as a comedy. For her adaptation, she says in a note, she wanted the audience to see and understand Strindberg’s play. Aronson’s version begins with Jean (Ivette Dumeng) and her show dog Maid Marian (played by actress Katie Ostrowski), a Hungarian sheepdog, frolicking in the park, enjoying their time as they wait for Jean’s husband, Maurice (Randall Rodriguez). Emile, Jean’s brother, later joins them, and they discuss Jean’s concern that Maurice is planning to leave her. (Aronson doesn’t explain why these residents of New York should have French names.)

Jean is afraid that she will not be able to afford Maid Marian’s dog show expenses if Maurice divorces her. Emile and Jean speak of how Maurice, an author, rarely takes her on his book tours or to social affairs. She tells Emile, “I don’t know, but I have a feeling that something dreadful is in store for me.” Suddenly Maurice appears and begins caressing Maid Marian, whom he clearly loves. He also gives the impression that he loves Jean and enjoys her company and physicality. In fact, he invites her to the opening of one of his plays and she refuses. She tells him she will be better at home with Maid Marian. They part ways, and the play begins to unfold the “something dreadful” that Jean fears.

Maurice goes off to meet and start an affair with Henriette (Christina Toth), who is in a lesbian relationship with his close friend (a man plays the friend in Strindberg’s original). The tension increases: Maurice must now decide if he stays with his wife or goes with his new lover. As he contemplates his decision and how difficult it would be to see Maid Marian if he divorces Jean, the dog mysteriously dies.

One of Aronson’s most radical changes to Strindberg’s original text is that Maid Marian is a replacement for the mistress’s daughter. She writes that she made this choice because she wanted the play to be more believable: “I actually did it because in the original, the child dies and nobody really cares.”

Although there’s a logic behind Aronson’s choice, it may not resonate with the same intensity as Strindberg’s. “I thought that the audience would not be able to forgive anyone in the play for so easily moving on from the death of a human child. A treasured animal’s death, though tragic and upsetting, is more consistent with the general reaction and behavior that Strindberg’s characters demonstrate.”

But even though the change from child to animal does lighten the mood and makes Maurice’s actions somewhat more forgivable, some of the plot stretches credibility. After the dog’s death, animal law enforcement appears to investigate the crime. As serious a crime as animal abuse is, it seems rather fantastical that a Broadway-type play would be pulled because of animal abuse. In any case, Maurice is charged as the main suspect, but he is eventually exonerated. Within hours of his release, Maurice’s reputation is ruined, and his play is pulled.

Whether the choice to change the daughter to a sheepdog is fully justified or not, it does not take away from the lightness of the play. It does, however, make the circumstance melodramatic and absurd, which brings out the humor in the play.

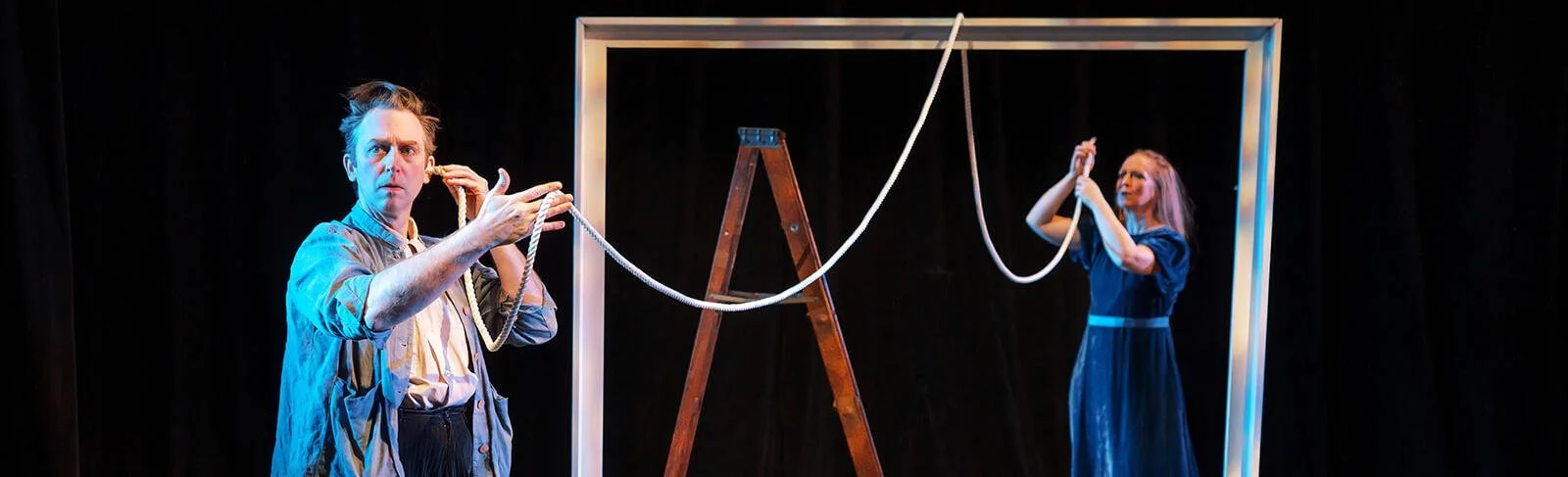

Matthew Hampton and Holly Albrach’s costuming of the characters is impeccable: fashionable and in line with the current New York scene. They employ an approach to the Hungarian sheepdog that seems to draw inspiration from puppet theater. It was entertaining and just simply delightful to the eye.

The sound design by Andy Evan Cohen makes the transition between scenes lively, using instrumentals of popular pop songs. They are played with a classical twist, so the audience is left to try and identify the familiar tune.

Aronson has accomplished her goal. The play has witty moments and comic scenes. The absurdism makes for great melodramatic humor as well. The revision keeps the audience focused on its entertaining and engaging story for the entire duration.

Crimes and Crimes plays through Aug. 20 at the Gene Frankel Theatre, 24 Bond St., in Manhattan. For tickets, call (212) 868-4444 or visit www.strindbergrep.com.