Although the slang term for heterosexuals is the title of Dan Giles’s new play, it doesn’t technically apply to the main human characters, a gay couple, but rather to a pair of hamsters that they are looking after. Giles’s amusing and well-acted comedy has a great deal to say about both sexual and parental love; about the open discussion necessary to keep relationships functioning; and about the neuroses that all couples in the animal kingdom experience.

Omega Kids

Noah Mease’s play Omega Kids takes its name from a fictional comic book at the center of its story. In the comic, eight super-powered teens regroup in their hideaway following the traumatic loss of their leader. The weight of the past and apprehension for the future create a recriminatory atmosphere that threatens to turn violent until Kyle Kelley, the “Insomniac,” puts everyone to sleep. When Lucas Augur, “recently magical,” wakes up, he and Kyle take the first halting steps toward romance, acting on an attraction that until now has been merely implicit. The play itself is about a different pair of traumatized youths stumbling toward connection. What they’re looking for in each other, however, can’t be so easily classified.

Sight Unseen

Donald Margulies, one of the most accomplished American playwrights, is probably less famous than he should be, in spite of a Pulitzer Prize for Dinner With Friends (2000) and notable achievements such as Collected Stories (1996) and Time Stands Still (2010). It’s unlikely that the shoestring production of Sight Unseen at the charming Access Theater will add significantly to his reputation, but an exceptional cast and astute direction make the quaint, four-flight walkup worthwhile for theater lovers. (An elevator is also available.)

(Un)Happy Family

Tolstoy said: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” The origins of unhappiness are certainly a unique combination for every family. For the one in Ann Adams’s Strange Country, directed by Jay Stull at the Access Theater, mental illness, lack of loyalty, and addiction are the sources that lead to complications between siblings.

The play opens on a one-room efficiency apartment: beer cans, leftover foods and trash are strewn everywhere. The occupant, Darryl (Sidney Williams), is fast asleep on the couch, until his sister, Tiffany (Vanessa Vache), lets herself in. After she puts food in the refrigerator, she assesses the situation and wakes him up by spraying him with Fabreze. Roused from his sleep, Darryl cries: “That shit will give you cancer!” The irony of the line is not lost on Tiffany. Darryl is a slob who seems completely unconcerned with his personal hygiene, the cleanliness of his apartment, or his health. He even confesses that he medicates himself on a steady stream of beer and meds.

Tiffany gently tosses back an ironic barb of her own: “Maybe you’ll eat your dinner one day, rather than drink it.” As Tiffany bangs around the apartment trying to clean up, she orders her brother to go wash up so they can go to their mother’s re-commitment ceremony. This brings on a stalemate.

Tiffany seems abrasive and angry, but underneath her volatile outbursts and no-nonsense demeanor is a woman who really cares about her family. If she didn’t care so much, she wouldn’t spend her morning goading Darryl and trying to do what’s best for her family. This concern extends to her girlfriend, Jamie (Bethany Geraghty), who is stony-faced and avoids eye contact with Darryl. She seems highly displeased with the situation.

At one point in the play, which moves along organically even though the dialogue is a bit stultified in places, Darryl and Jamie find themselves alone in Darryl’s apartment. Darryl is thrilled to discover they are both trying to move forward while simultaneously being moored by addiction. He practically whoops: “You’re the first person who’s made me feel good about myself” and “You’re more fucked-up than me!”

While Tiffany tries hard to keep the family together, Darryl steadily consumes beer. As he opens one can after another, the sound of the initial pop of the tab, and then the fizz of the beer become a soundtrack for his character. Nonetheless, Darryl is like the idiot savant, or the fool in Shakespeare’s plays. For all his slovenly drunkenness, he has wisdom and insight. He’s right on when he says plaintively to Tiffany: “The whole of your life is trying to fix people who don’t want to be fixed. But you cling to it.” He knows her life’s purpose is to stay close to her family and try to keep them together, but he can’t help and doesn’t want to.

Strange Country does a good job of capturing the sadness that is brought on when a family member is suffering from a problem that is too difficult to fix. However, it also explores the complicated idea that what may be good for one person may not be good for another. Everyone has his own way of surviving, and the measures people use may not always be the right ones. For Darryl, this is his way of surviving; it’s his “normal.” Tiffany has another “normal,” a more conventional and socially acceptable one. But she doesn’t seem happy. Although Darryl seems less productive and more destructive, he seems more content with his life and himself. It’s a philosophical conundrum.

Strange Country by Anne Adams, produced by New Light Theater Project, runs until Aug. 13 at 8 p.m. Wednesday–Saturdays at Access Theater(380 Broadway at White Street, in Tribeca). Tickets are $15 in advance, $18 at the door, and can be purchased online at: http://www.newlighttheaterproject.com.

Nightmare on the High Seas

If art is about digging beneath the surfaces of things and restoring wholeness to human experience, run to see In The Soundless Awe, an important new play by Jayme McGhan and Andy Pederson now playing at Access Theater until Dec. 12. One of three plays in repertory with the New Light Theater Project (NLTP), it is beautifully produced and imaginatively directed by Sarah Norris, a founding artistic director of the NLTP company.

At the heart of the play is Captain Charles Butler McVay III, a highly decorated third generation Navy officer and the commander of the U.S.S. Indianapolis when two Japanese torpedoes struck it just after midnight on July 30, 1945. Three hundred men were killed in the first 12 minutes it took the ship to sink. Over the next five days, 900 more languished unsheltered on the high seas fighting sun, sharks, dehydration, starvation and exhaustion while anticipating rescue any minute. Three SOS signals had been sent as the ship went down but 600 more men would die before survivors were accidentally sighted by pilots on a routine patrol and rescued. It was the largest loss of life in U.S. naval history. McVay was court-martialed and found guilty of “failing to zigzag,” a way of steering to avoid enemy fire, although this maneuver was technically at the discretion of the commanding officer (himself).

How does one plumb such an experience: five days, 900 men and the mothers, fathers, wives and children forever caught in its vast net? This might have been a play about a Navy cover-up: its failure to provide standard destroyer escort for the ship (although six days earlier a destroyer was similarly torpedoed on the same route); and its mangled rescue operation that inexcusably left 900 men in the cold Pacific waters for five interminable days. But In The Soundless Awe is less about events—a sinking, court martial and suicide—than about an experience that is simply beyond the ability of the mind to grasp. What do we do with such an experience? What does it look like? What are its consequences for the survivors? For the families of those who did not survive? And for our navy and military, which in deflecting blame to one of its own, set the stage, the writers imply, for cover-ups to come in Vietnam and elsewhere. For us?

This is a deftly written and ambitious script that zigzags back and forth in real-time, in remembered time and in imagined time not so much as a way to tell us a story as to imitate the flow of mind itself in its perpetual return to the frozen moment, to the five days on the high seas which will forever imprison those who lived through it. On stage the bodies of the actors freeze and unfreeze as they play out the bits and pieces of this terrible scene: attempts of the Captain and his crew to distract themselves, delusions of help on a horizon, sharing the little water they had, discovering that a mate has lost a leg to a shark, the dying of the men one by one. A suggestive and repeating motif, the Gray Lady (Hallie Wage), a beautiful and tempting siren of death and release, pulls the dying off stage but also dances with McVay. The Captain imagines a meeting with his stern and distant father and plays cards with friends years after his court martial, but his mind always returns to those five days on the water until he steps out of time itself by raising a gun to his head.

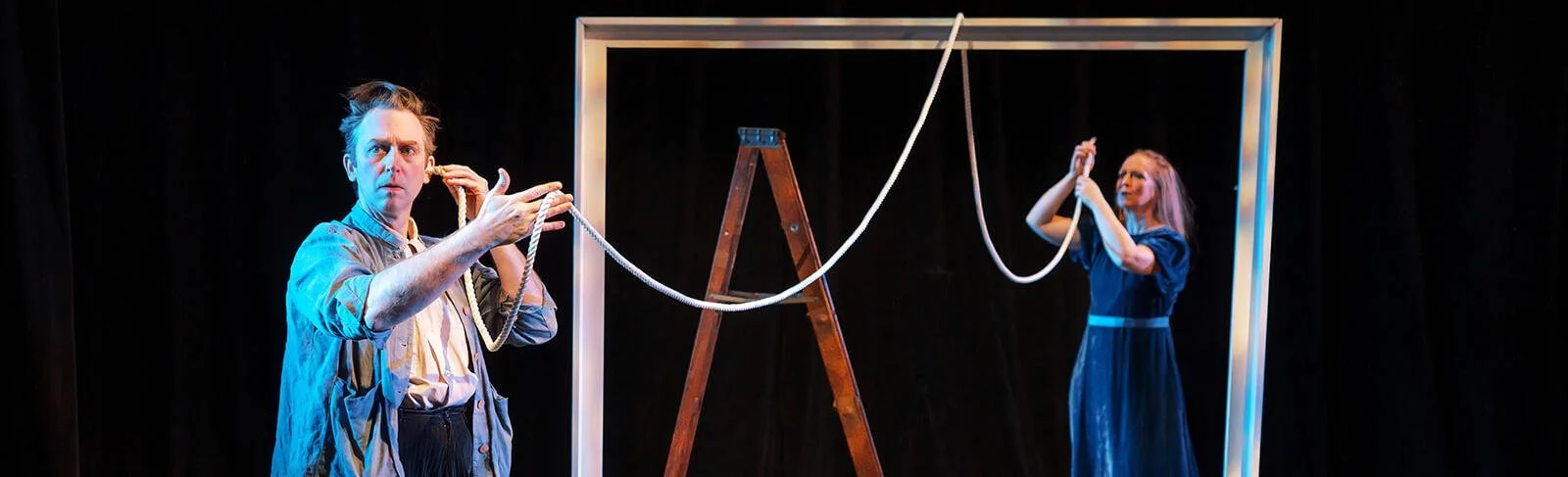

The actors work in a theatrical style in which choreographed movement and gesture, video, lighting and sound matter as much as, or even more, than the words spoken. A stage direction includes a note: “nightmarish and Kafkaesque,” but so much more in the production is not in the script—the eerie blue light that bathes the stage when we first enter the theater; video clips noting each day on the water and how many men are still living. Phantasmagoria and metaphor are the keys to the excavation of the inner world of McVay, but also to a shared human interior. The creative direction of Norris and her brilliant creative and production team deepen the script and give the play its juice and strange beauty. The ensemble, who take on a variety of roles, are outstanding. The two actors who play McVay as a young man and as an old man, Chris Kipiniak and Leo Farley, are convincing.

In The Soundless Awe is a well-executed, well-conceived and beautifully produced play. What makes it important is that it enlarges the violated human dimension of a terrible event in our shared American history. It opens our hearts and imagination to the wartime experience of men who sacrificed for our common welfare.

In Soundless Awe” runs until Dec. 12 at Access Theater (380 Broadway, 4th Floor, between White and Walker Sts.) in lower Manhattan. Performances run Thursday-Saturday at 8 p.m. Check NewLightTheaterProject.com for the exact schedule. Tickets are $15 and can be purchased by calling 800-838-3006 or visiting BrownPaperTickets.com. Limited blocks of free and discount tickets for veterans or active-duty personnel are available. Inquire at NewLightTheaterProject@gmail.com.