In 1972, wealthy Parisian socialite Marie-Hélène de Rothschild threw an elaborately occult Illuminati Ball at her family’s chateau. Guests of honor included Salvador Dali and Audrey Hepburn, and the coveted invitations requested “black tie, long dresses, & Surrealist heads.” Today, nearly 50 years later, immersive maven Cynthia von Buhler reimagines the Illuminati Ball at her estate, and her guest list could include you. Known for her previous immersive productions Speakeasy Dollhouse and Midnight Frolic, von Buhler is at it again with her most exclusive experience yet.

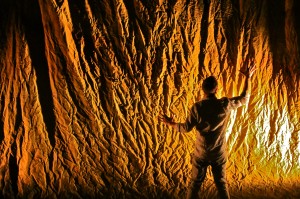

Like the original Rothschild event, von Buhler takes care to construct an atmosphere of selectivity and secrecy beginning at the participant’s initial point of entry. Potential guests must apply for attendance and, once chosen, are delivered precise instructions on what to wear and where to meet. Von Buhler then shuttles participants to her estate via a limousine fitted with blackout curtains. For even the most seasoned immersive theatergoers, the secretive applications, invitations, and strict instructions are enough to drum up some excitement and anticipation about the evening to come.

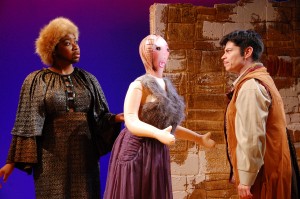

While the individual talents of the interspersed performances provide ample diversions, certain aspects of The Illuminati Ball disrupt its immersive flow. A bit of shuffling amongst organizers while boarding and riding the limousine partially dispels the illusion that participants are actually being considered for candidacy in the Illuminati. While it is no small feat to conceal the complicated logistics involved in such an elaborate immersive experience, the success of the production relies on this very concealment. Furthermore, Illuminati Ball seems only partially committed to its narrative. Some performers, such as the honey-voiced Eden Atencio as Kamadhenu and von Buhler herself as the heiress of the estate, seem more committed to interacting candidly with audience members. Other characters seem more concerned with advancing the plot, which crescendos confusingly in the middle of dessert. Transitions between dinner, group scenes, and individual interactions feel a bit like herding cats.

Casting the production’s somewhat disjointed storyline aside, Illuminati Ball provides something else far more special in its discarding of the fourth wall. The ability to eat with and interact with the actors and the fellow attendees is the production’s greatest joy.

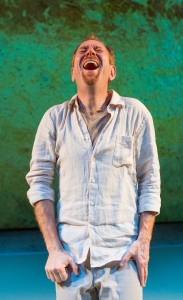

The conviviality is amplified by the evening’s spread of small plates and cocktails, the quality of which far surpasses any usual dinner theater fare. The dinner, lovingly prepared and artfully plated by chef Erin Orr, consists of delightful colors and textures. The real sorcerer behind this production is mixologist Bootleg Greg, whose (virtually unlimited) flavorful concoctions fuel the evening’s revelry. For better or for worse, the drama of Illuminati’s muddled storyline is eclipsed by the evening’s more sensual pleasures of food, drink, socialization, music, and dance. In any case, the most pleasant surprise of The Illuminati Ball is its unique ability to facilitate connections among audience members, actors, and performers as they carouse in the moonlight.

The Illuminati Ball: An Immersive Excursion by Cynthia von Buhler runs bi-monthly on Saturday evenings through Aug. 20 (specific dates here) at 6 p.m. at a secret location one hour outside of Manhattan. Apply for attendance here.