Small Mouth Sounds is an apt title for Bess Wohl’s new play, since the work explores a spiritual retreat where silence is the rule. The six characters on the retreat use mostly facial expressions and gestures to make themselves understood, and director Rachel Chavkin has cast the production at Ars Nova with wonderful faces, worthy of a silent film. They communicate much without words.

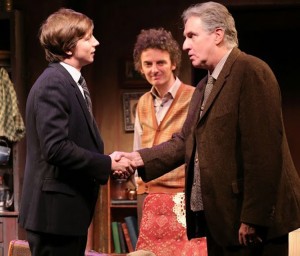

There’s Marcia Debonis as Joan, a middle-aged lesbian with an insistently worried look. Her partner, Judy (Sakina Jaffrey), slighter and dark-haired, appears more composed but also troubled. Babak Tafti is a conventionally handsome attendee whom Joan recognizes as a renowned yoga teacher named Rodney, a star of his own videos. Tall, bearded Erik Lochtefeld as Jan is annoyed by the bugs, especially mosquitoes, while Brad Heberlee’s pale Ned wears a kufi cap and is exasperated by rule-breakers, particularly the self-important Rodney. Lastly there is Jessica Almasy as the scattered Alicia, a young woman who arrives late, eats snacks, and uses her cellphone at will, ignoring the rules established by the Teacher, a disembodied voice (Jojo Gonzalez).

In Chavkin's unusual traverse staging, the action takes place between two banks of seats where the audience sits; in addition, there is a dais with chairs at one end where the six participants occasionally gather to listen to the Teacher. The effect is to bring us close to the actors, and though one side of the audience may briefly not see an actor’s face, Chavkin has used the space and the actors skillfully; one never feels that anything crucial has been missed.

Only Heberlee as Ned gets a long monologue. The rest of the communication is in fits and snatches, and occasional whispers, except for the Teacher, who begins the week with a parable about a well frog and a traveling frog; the latter takes the well frog out of his well and shows him the ocean, with disastrous results. Even with minimal dialogue, however, one can deduce a great deal. Alicia is clearly emotionally vulnerable after a disastrous relationship; her whispered cell calls to someone named Ben, who never picks up, affirm it. Joan becomes upset at the mention of cancer and weeps, and she flees the room when the Teacher says, “If you want to avoid pain, it is impossible.” But Wohl nicely upsets one’s expectations of why.

There are rituals involved. The group sleeps together, carrying lanterns, tatami mats and thin blankets to the sleeping area and awkwardly sorts out who sleeps next to whom. Wohl pokes gentle fun at them, but she’s never brutally satiric; one cares about the characters, in spite of whatever burdens have brought them to this pass and their inability to articulate at will. In addition to the parable, the Teacher asks the participants to follow the Asian practice of putting something on paper—in this case, the intention for the weekend; at the end, he instructs them to set it afire.

During the retreat we observe Judy and Joan at loggerheads, and Joan cries in the night. Judy, who is more composed, seems to click with Jan, possibly even romantically, as they “talk” about the bugs and he shows her a picture of his dead son. Rodney makes a play for Alicia, and Ned fumes jealously because he also is attracted to her.

Ars Nova presents Small Mouth Sounds through April 25 at 511 West 54th St. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Monday through Wednesday and 8 p.m. Thursday through Saturday. Matinees are at 2 p.m. on Saturday. Tickets are $35 and may be purchased by visiting www.arsnova.com or calling OvationTix at (866) 811-4111.