Incantata, by Pulitzer Prize–winning Irish poet Paul Muldoon, is an elegy crafted into a theatrical narrative that loosely weaves together erudite poetic imagery and concrete memories with literary and artistic references. The experience is a journey through bumpy waters, a sensory and linguistic adventure with Stanley Townsend, a tremendously talented and physical actor, at the helm of the solo show.

The Mountains Look Different

Set on Midsummer’s Eve (June 23), Micheál mac Liammóir’s The Mountains Look Different is about a woman’s attempt to reinvent herself through marriage following years of working as a prostitute in London. First performed at the Gate Theater in Dublin, the noted Irish actor’s play was applauded for its openness by critics and audiences in 1948, but it was also disdained by the God-fearing and narrow-minded Catholic community. However bold it was then, by today’s standards director Aidan Redmond’s revival offers audiences little more than a diorama, a 3-D representation of a bygone era.

Woman and Scarecrow

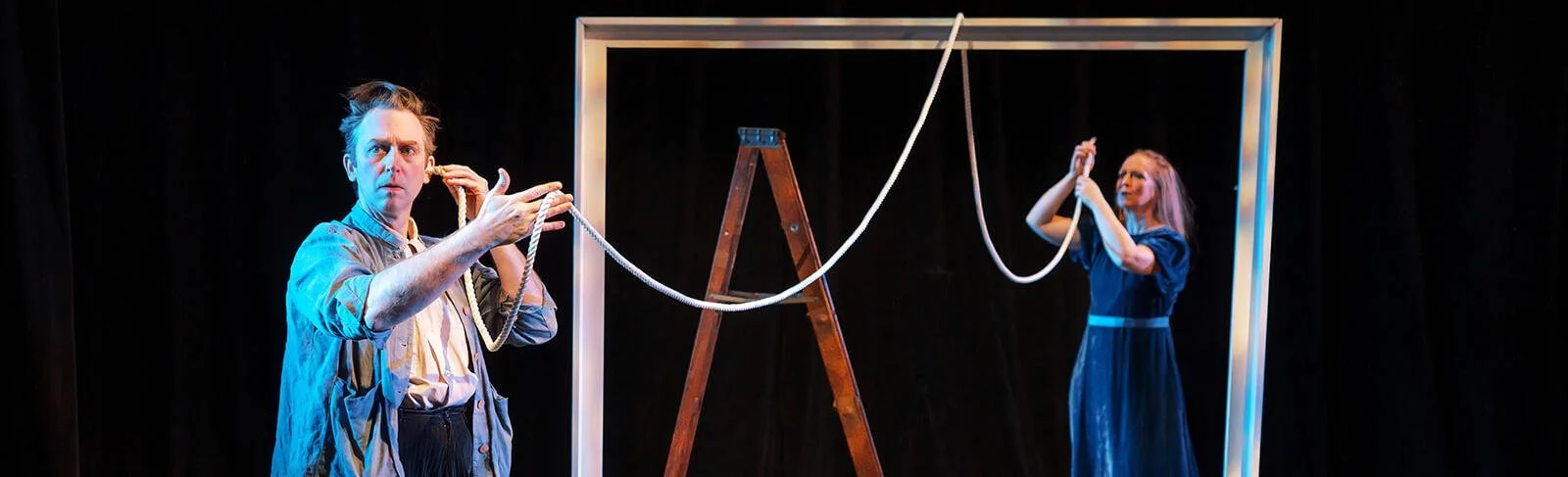

Irish playwright Marina Carr attempts to capture the thoughts and sentiments of a woman during her last hours alive in Woman and Scarecrow. With skillful direction by Ciarán O’Reilly, this production delves into the innermost feelings of a woman who is learning about the meaning of life at the last possible moment. Carr has chosen to use general character names that could represent anyone, to suggest a universality to the situation: the principals here are Woman, Scarecrow, Him, Aunty Ah and Thing.

Paranormal Problems

For the first production by Irish Repertory Theatre on its return to its 22nd Street location after a year’s renovation and exile, artistic director Charlotte Moore has chosen (or perhaps approved) Conor McPherson’s Shining City, a 2004 play about a psychiatrist and his patient who wrestle with secrets and regrets that is directed by longtime associate Ciarán O’Reilly. (Shining City was eventually seen on Broadway in 2006.) In some ways the play is a mixed bag: McPherson’s early works, such as The Weir (1997) and Port Authority (2003), rely on interrelated monologues to tell a story. In The Weir, for instance, a group of people gather in a bar and tell ghost stories, one by one. In later works, such as The Seafarer and The Night Alive, McPherson becomes less reliant on speeches than on give-and-take that resembles real conversation.

Shining City concerns a Dublin psychiatrist, Ian (Billy Carter), who has taken on a patient, John, a man who cannot sleep in his home since he saw the ghost of his dead wife, Maury, killed in a violent traffic accident. Played by Matthew Broderick with a deft Irish brogue, John is worried about his sanity. The memory of the apparition haunts him, and he cannot stay overnight in his home. John seeks Ian’s help in restoring him to sleep at night. In a series of near-monologues with the psychiatrist, John reviews his life and marriage.

Ian, meanwhile, has troubles of his own. He wants out of his marriage to Lisa Dwan’s Neasa, and when Neasa arrives and listens to him explain, she seems rather a dunce, cottoning to the fact that he’s leaving her long after the audience knows it. The couple have a row in his home office, and he assures her he’ll take care of her but that he won’t return to the marriage. There’s less give-and-take than there is of Ian’s staking out his position fully, and then Neasa delivering her side of the story. O’Reilly’s direction can’t disguise that the playwright is still adapting to conversational back-and-forth.

Anyone familiar with McPherson’s work knows that something eerie is going to happen, but when it does, unfortunately, the effect is much less chilling than it was in the Broadway production. Whether it’s due to Broderick’s laid-back delivery, which, although an appropriate choice for the character, somehow makes the proceedings too cozy, and the audience too comfortable, or whether O’Reilly’s staging simply fails to do the moment justice, is unclear.

But Broderick is doing better work than he has in a long time. He’s taken on a gigantic role and he’s never less than enjoyable in it. Billy Carter as the psychiatrist is also exemplary. His Ian is energetic, sympathetic, emotionally torn and yet willing to face hard truths. A late entrance by James Russell’s Laurence, a pickup for sex, reveals much about Ian, who abandoned the priesthood in order to marry Neasa. Yet a final scene further complicates the nature of Ian’s character, and one senses that perceptions are not to be relied upon. It calls to mind Hamlet’s observation, “There is more in heaven and earth, Horatio, than is dreamt of in your philosophy.” It's a good epigraph for the play’s finale as well.

That Ian’s name is the Gaelic version of “John” is a subtle hint at the haunting climax. The Irish Rep’s Shining City is a satisfying, if not ideal, rendering of what feels like a transitional play by an important modern playwright.

The Irish Rep’s Shining City plays through July 3 at the company’s refurbished home at 132 W. 22 St. in Manhattan. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday and Thursday and at 8 p.m. Wednesday, Friday and Saturday. Matinees are at 3 p.m. Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday. For tickets, call Ovationtix at (212) 727-2737 or visit irishrep.org.