Quicksand is an apt name for the ambitious world premiere production of Regina Robbins’ theatrical adaptation of Nella Larsen’s semi-autobiographical work of fiction, written in 1928 and set in the same period. It chronicles the story of Helga Crane, a woman of both mixed ancestry and mixed race, who is, for that very reason, a tortured soul.

Born to a black, West Indian father who disappeared soon after her birth, and a white, Danish mother who raised her in the U.S. and in Denmark, the fair-skinned and exotic-looking Helga (Gabrielle Laurendine) cannot escape her bilingual, bicultural and biracial status. Her mother died when she was 15; her mother’s brother sent her away to school, where she received a good education; and she became a teacher at an all-black college. The conflict between her white and black selves produced a complex psychological character. Helga carries around a lot of heavy baggage, literally and figuratively, and her pain is palpable.

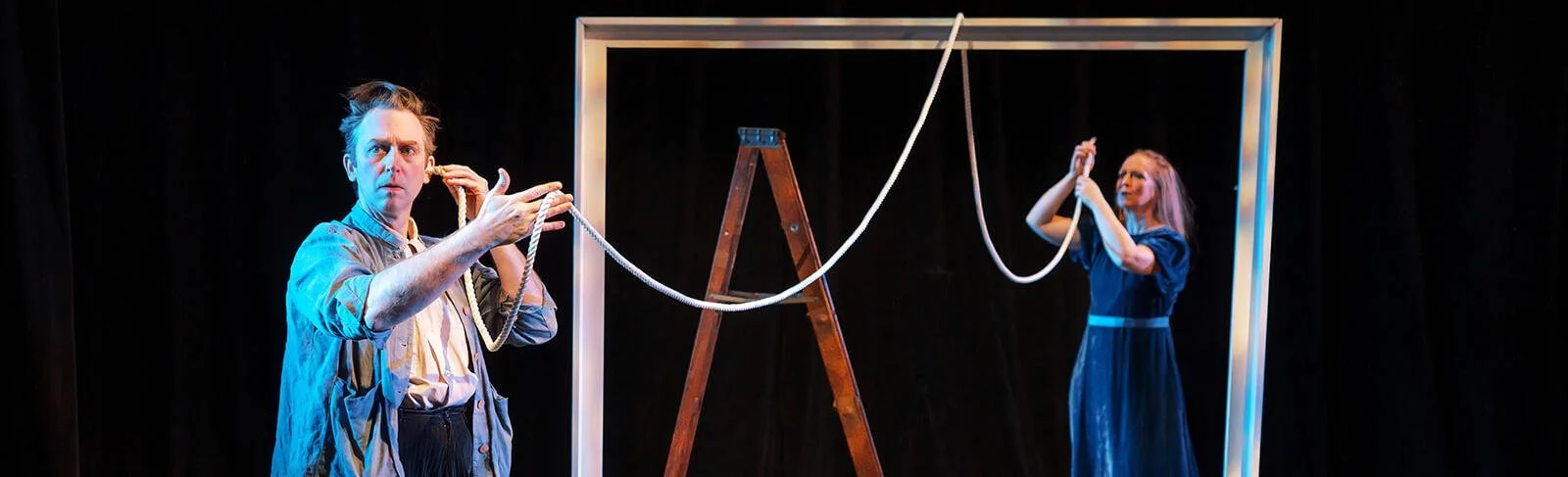

Gabrielle Laurendine, playing the exotic and enigmatic Helga Crane, poses for famous Danish painter Axel Olsen (Michael Quattrone) in Quicksand. Top: Laurendine’s Helga surrounded by the Ensemble. Photographs by Anais Koivisto.

The play begins in Tennessee, where she announces that she is quitting her teaching job, because she is “frustrated,” “tired” and “disgusted” by the “hypocrisy” and “cruelty” that pervade the all-black college, Naxos. Here, Laurendine’s Helga makes the first of many on-stage costume changes (the costumes are by Asia-Anansi McCallum). She also packs a hefty leather suitcase and boards the train to Chicago, hoping her uncle, Peter Nilssen, will be there for her. Her optimism is quashed by her uncle’s new wife, who is appalled by the mixed-race Helga’s claim to be family, and who assures her, “I am not your aunt, and my husband is not your uncle. Do not come back here.” The church provides Helga with no solace either, and she dismisses religion as “hollow” and “phony,” saying, “No one here cares about me.”

With no hope of permanent work and no one to keep her in Chicago, Helga gets a temporary position assisting a Harlem-based socialite, Mrs. Hayes-Rore (Veronique Jeanmarie) and finds her way to New York City. She is encouraged by the warm welcome she receives in Harlem, and is stimulated by the cultural and social renaissance of the 1920s under way there, but it’s not long before she becomes restless and dissatisfied. A letter from her uncle in Chicago, terminating his relationship with her, advises her to go to Denmark; he encloses a check for $5,000 which helps her decision to move on again.

Denmark offers Helga a reception that is entirely different. Her Danish aunt and uncle embrace her; they provide her with a loving home and access to a bourgeois lifestyle; they introduce her to several eligible men, one of whom proposes to her, but she refuses to enter into a mixed marriage. Heading back to New York again, Helga struggles to find a place where she can feel at home.

“The conflict between her white and black selves produced a complex psychological character. Helga carries around a lot of heavy baggage, literally and figuratively, and her pain is palpable.”

Interesting though Helga’s story may be, Anais Koivisto’s production is too long. It’s laden with layers of exposition, (including flashbacks, which are not incongruous but which can be a distraction; they ultimately confuse the flow, until the relevance becomes clear a beat or so afterward). It feels as if every single page of the novel is being acted out, with some repetition for emphasis, resulting in a sinking, never-ending feeling.

It is also weighed down by a large number of historical, social, cultural, and literary references. There are appearances by Booker T. Washington, Paul Robeson, and Al Jolson, to name a few. Many of them are lost amid the sheer volume of information the audience is asked to consume. A story of such epic proportions might work better if it were broken up into parts—there is enough material here for a trilogy.

On the other hand, the show is lifted and well-supported by charming interludes such as the train journey; the walk through Chicago, and the soup of the day, which are cleverly achieved by Allison Beler’s choreography, Tekla Monson’s simple, moveable set, and a versatile 11-actor ensemble that also serves as a chorus. Special credit goes to Laurendine, along with Malloree Hill, who plays Aunt Katrina, and Chris Wight as Uncle Paul for performing the opening scene of Act II in Danish, and managing to get their message across!

Quicksand is at the IRT Theater (154 Christopher St., between Washington and Greenwich streets) through Dec. 15. Performances are at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday, with added performances at 3 p.m. Dec. 7; 7:30 p.m. on Dec. 9; and at 4 and 8 p.m. on Dec. 11. For tickets and more information, call Brown Paper Tickets at (800) 838-3006 or visit www.everydayinferno.com.