When newspaper editor Hovstad cries, "We must destroy this myth that our leaders are infallible," in the rousing performance of Public Enemy at the Pearl Theatre Company, the audience titters and sighs. That same day, the Washington Post had released a tape of presidential nominee Donald Trump making extremely lewd remarks about women. With Trump's words ringing in the collective consciousness of the audience, playwright David Harrower's adaptation of Henrik Ibsen's 1882 play An Enemy of the People has transposed an almost 150-year-old story about small-town bureaucracy to the higher, tenser key of our present-day political landscape. That is not to say that Public Enemy is toxic, exhausting or anything like the American political process has been this past year. On the contrary, it rejuvenates the public with an eloquent tale of justice and ambition.

Director Hal Brooks, who is artistic director of the Pearl, has confirmed the company's commitment to showcasing incisive, relevant classical theater with Harrower's masterly take on one of the Norwegian playwright's lesser-known plays. Written as a biting response to critics, whose moralistic reviews he despised, Ibsen deliberately set out to magnify the hypocrisy of human nature, and how it is writ especially large in political processes. He chooses to place his little human drama in a fairly provincial town, where the family of Dr. Thomas Stockmann (Jimmon Cole) and his wife (Nilaja Sun) is enjoying a life of newly-found comfort—they're on the upswing after some hard financial times.

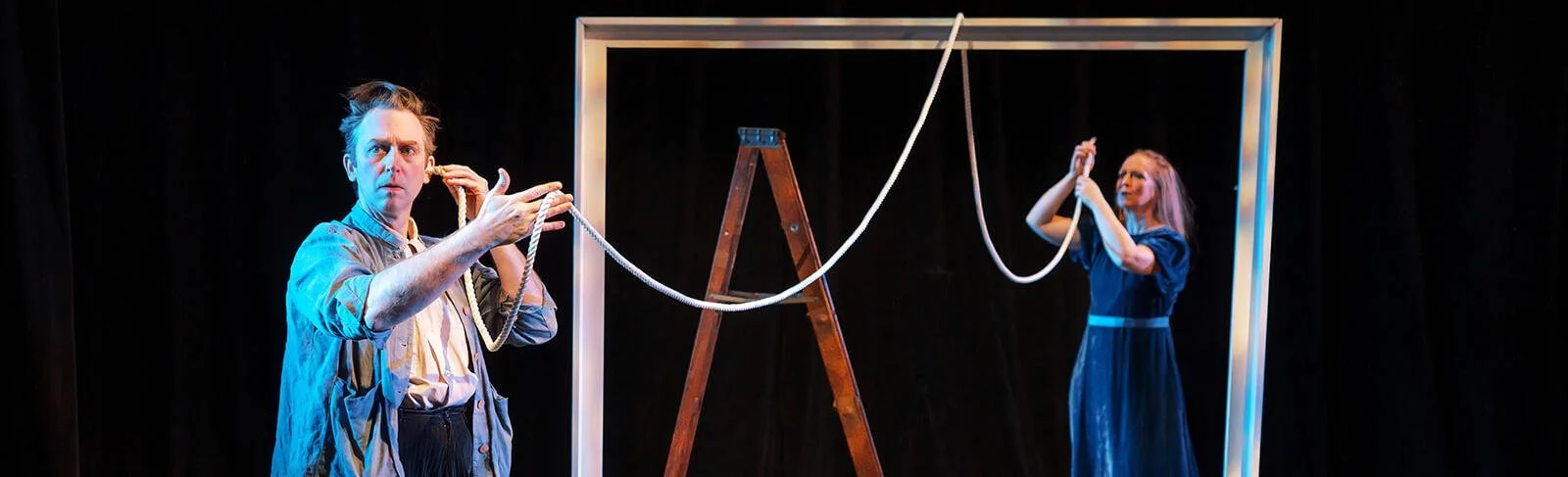

Also in the mix are the Stockmanns' friends: fiery newspapermen Hovstad (Robert Tann) and Billing (Alex Purcell), and world-weary sailor Horster (Carol Schultz). Thomas's brother, Peter (Guiesseppe Jones), is the disciplined, severe, and fastidious mayor of the town; in short, he is nothing like his open, intellectual and charismatic brother. When Thomas discovers that the town's famous baths are swimming with lethal bacteria, and that Peter is attempting to cover up the discovery with threats against his security and his family, Thomas is forced to decide between standing by his ideals as a physician, or enveloping himself in willful ignorance.

Cole has an easy, eager charisma about him. It's part of what makes Stockmann's character the Messianic figure in his small town. His truth-seeking is admirable, and recalls Bernie Sanders' inspiring messages, but Stockmann is more interesting than his real-life counterpart. For one thing, he is scaled down to fit the stuffy intimacy of a small town (scenic designer Harry Feiner has built a subdued, wooden interior for the Stockmanns’ home, while costumer Barbara A. Bell elegantly signifies the passage of time with the wear and tear of the characters' clothes). Cole does not scale down his part, however: with his sonorous voice and endearingly bitter humor, he renders Stockmann larger than life.

His brother the mayor, played by Jones, is a blustering, up-for-the-challenge sparring partner. Fastidious and severe, Peter raises the hackles of more than one “reformist,” namely Hovstad and Billing. Their personalities knot up nicely toward the latter half of the play, as does Arielle Goldman's Petra, the Stockmanns' daughter, a teacher. John Keating, who plays a businessman called Aslasken, is a particular revelation in his studied impression of a fickle everyman.

There is an unending tension between the authority and the reformist in Brooks's conception of Ibsen's play. Within this tension, however, is a complexity difficult to explore on stage: the variable nature of truth. Do we seek truth from our authority figures—policemen, politicians, councils of elders—or do we seek it from the reformers—journalists, leaders of movements, and the common man? When the disgraced Roman politician-turned-farmer Cincinnatus was called to serve as Rome's dictator during a period of social strife, he became a paragon of civic virtue when he resigned immediately after peace was restored, and picked up the plow again.

In An Enemy of the People, Ibsen quietly acknowledges that our most beloved leaders are impossible contradictions: they are both the authority and the reformist, both the leader and the common man. Harrower elegantly exposes Ibsen's sadder, but less delusional reality—that while we seek the truth of the reformer (Thomas Stockmann), we give way to fear and accept the truth of the authority (Peter Stockmann). Let's hope our current political theater, with all its muddy truths and maniacal lust for power, takes a note out of Brooks' precise, magnetic production of Ibsen's timely play.

Performances of Public Enemy run through Nov. 6 at the Pearl Theatre (555 West 42nd St.). Tickets are $69-$99 and may be purchased by calling (212) 563-9261 or visiting pearltheatre.org.