King Lear, with its epic sweep and enormous cast, is hard to get just right, but Michael Grandage’s production at the Brooklyn Academy of Music is overwhelmingly right and a must-see event. In Derek Jacobi, Grandage has a magisterial Lear, speaking the language with clarity and beauty and making sense—emotionally—even of the nonsense in the mad scenes.

The aged Iron Age king, as Shakespeareans know, has determined to divide his kingdom among his three daughters. But first he wants some flattery from them. The two eldest praise their father, while Lear’s favorite, Cordelia, responds that she has nothing to say and loses her third of the kingdom. Lear, of course, has his daughters’ true affections completely backwards. The combination of foolishness, vanity, irascibility, and majesty is hard to get just right, but Grandage and Jacobi have struck a winning balance in the crucial opening scene.

Though Jacobi’s Lear seems prickly and vain, he’s not so excessively overbearing that he seems to have planned to wring claims of affection from his daughters. It’s a thought that strikes Lear suddenly in Jacobi’s interpretation, and the direness of the situation is leavened by some brilliant stage business. Before Gina McKee’s Goneril, as the eldest, speaks, Jacobi holds up his hand to stop her: then he points to his cheek, she kisses it obediently, and he motions for her to continue. The comedy of the moment pays more dividends shortly after: when Justine Mitchell’s Regan is invited to begin, she unhesitatingly kisses Lear’s cheek, and he lets out a satisfied sigh to indicate that she’s just a bit better at knowing her duty than Goneril. These details are early indicators of how deeply Grandage and his actors have examined the text, and their humor helps rein in one’s inclination to outrage at the king’s abuse of Cordelia.

Jacobi’s Lear, while not blameless in his fate, justifies his assessment that he is “more sinned against than sinning.” It’s painful to see his fear that he may go mad, and when he finally becomes a sympathetic human being, he’s transcendent. He’s boosted by fine acting from the two antagonistic daughters. Both McKee’s Goneril and Mitchell’s Regan show unexpected sparks of humanity from time to time. Goneril cries when Lear puts a curse of sterility on her—a curse that Jacobi makes shocking. And even amid Regan’s later cruelties, Mitchell manages to show how painfully she loves Edmund.

There’s been a lot of judicious pruning of the mad scenes, both Lear’s and those of Gwilym Lee’s dashing, protective Edgar, to blend horror and grim comedy without alienating the audience with obscure references. In Act IV the mad Lear says, “There’s hell, there’s darkness.” In Jacobi’s reading, Lear mimics looking into a vagina—it’s very funny and yet draws on a classic Freudian fear.

There are minor quibbles, to be sure. It’s silly for Edgar to tell the blind Gloucester (a fine Paul Jesson, providing a sanguine parental counterpoint to Lear’s ire) to “look up” at the height from which he’s fallen when Gloucester has empty, bloody sockets, and Edgar is supposed to be a sighted passerby who’d notice that. And Alec Newman’s robust Edmund, one of Shakespeare’s juiciest roles, isn’t mesmerizing enough and doesn’t boost the character beyond stock melodramatic villain to something special. Gideon Turner’s Duke of Cornwall is the most disappointing: a 21st-century swaggering bully from a schoolyard playground, his duke lacks any gravitas.

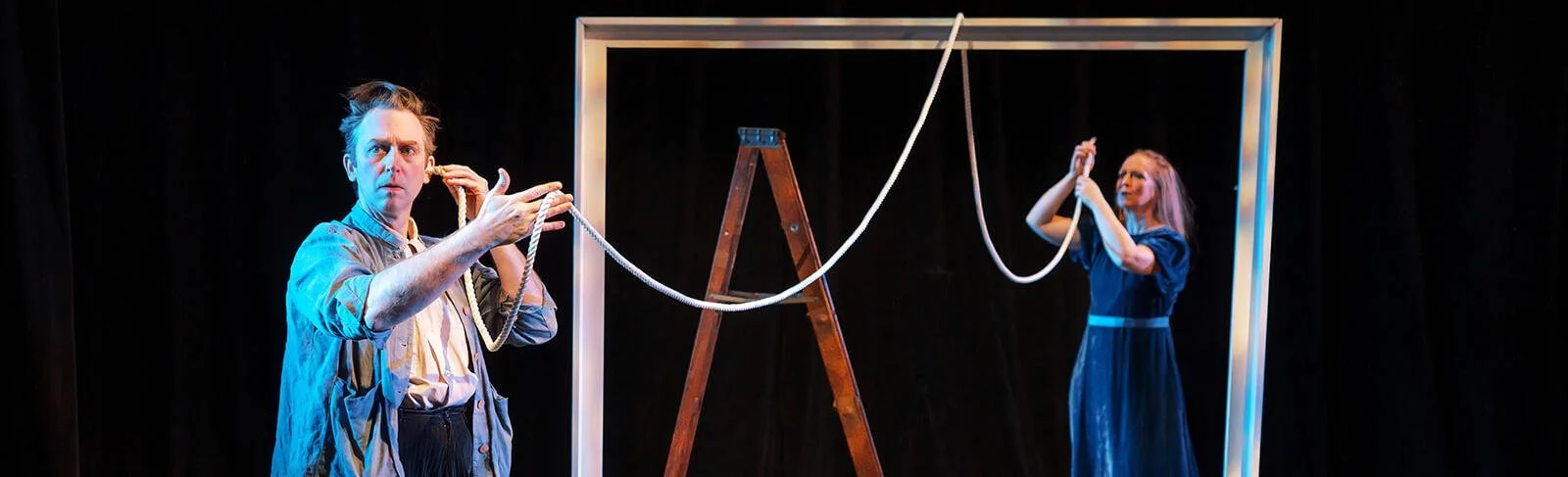

Grandage keeps the action moving swiftly in front of Christopher Oram’s curved set of high plank walls stippled in white, gray and brown. Later on, Neil Austin’s lighting makes the wall look carved in stone, yet even more astonishing is the storm scene; on the heath, lights flash beneath the stage floor and through cracks in the upright planks to simulate a torrent of rain, and the sound design of Adam Cork thunderously complements the effect.

Amid such high-caliber work, Jacobi's performance is still the crown jewel, exhibiting a mastery of timing and intonation. “I do not like the fashion of your garments,” the mad Lear says to Edgar, who’s in a loincloth on the heath. Then, as if anticipating the explanation: “You will say they are Persian.” It’s a very funny leap of imagination and the audience follows easily—never mind that Lear wouldn’t know the way Persians of his time dressed. It’s a measure of the success of the production that one cares about this choleric old man who has brought so much trouble down on his own head.

Tickets are scarce, but if you can score one, this is a King Lear that will stay in your memory a very long time.