Early in Carol Buggé’s new comedy-drama, Strings Attached, one of the author’s characters name-checks British writer Michael Frayn’s 1998 play Copenhagen, about an actual 1941 meeting between physicists Niels Bohr and Werner Heisenberg in the Danish capital. Buggé’s reference is a two-edged sword: her own work doesn’t come close to Frayn’s, but it does indicate that she has a passion and knowledge of physics that she wants to share with audiences. Frayn’s treatment is a rare instance of making science dramatically interesting, but Buggé’s overstuffed play is less viable.

Macbitches

Sophie McIntosh’s Macbitches is proof positive that some of the most exhilarating theater in New York City is being staged in Off-Off-Broadway houses. McIntosh’s 85-minute piece dramatizes what happens when Hailey (Marie Dinolan), a freshman acting major, is unexpectedly cast in the plum role of Lady Macbeth, and Rachel (Caroline Orlando), the queen bee of a college theater department in Minnesota, is left with big bruises on her ego.

On That Day in Amsterdam

On That Day in Amsterdam begins on a morning in 2015, after two young men have hooked up at a dance club in the Dutch metropolis. One of them, Kevin (Glenn Morizio), an American of Filipino extraction, is impatient to depart: he has a flight back to America later in the day, and he feels no emotional connection. The other, Sammy (Ahmad Maksoud), hopes to know Kevin better and nudges him to have breakfast. A heavy snow delays Kevin’s trip, and what ensues in Clarence Coo’s emotionally reverberating play expands to far more than a gay love story: it is a moving drama about life’s fleeting encounters, loss, nostalgia, home, art, and memory, told in scenes that skip through centuries.

Under the Dragon’s Tail

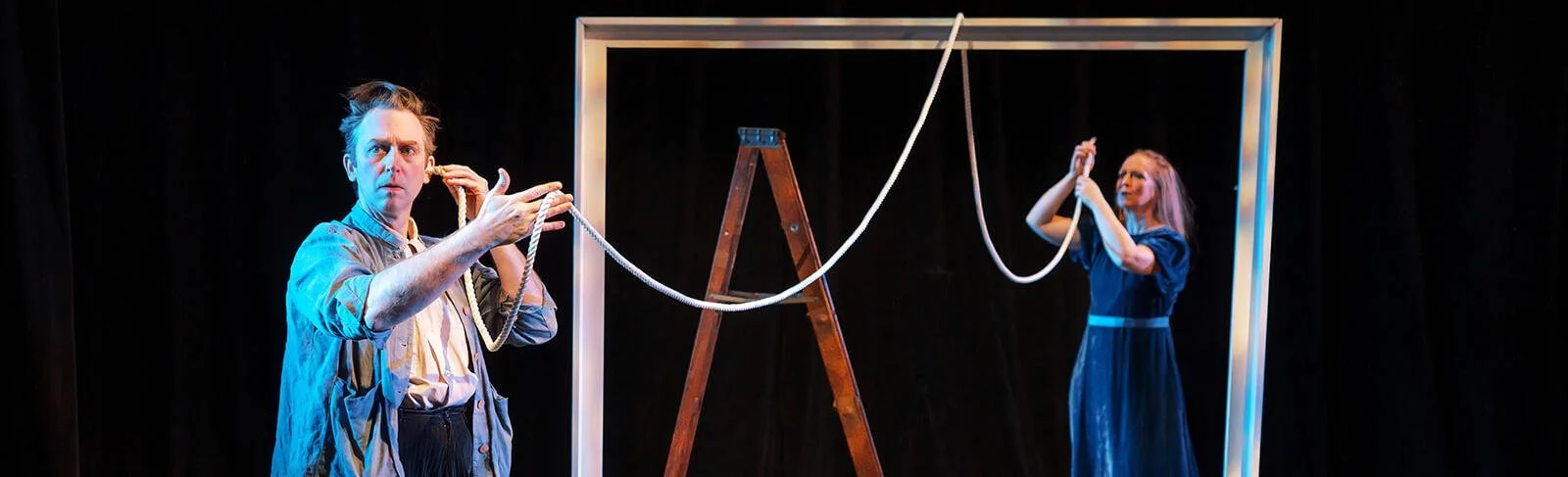

On the lam criminals, a would-be king living as an exiled stoner, an untethered cosmonaut, and a pair of lovers sorting through the detritus of a terminated relationship—are the characters populating Isaac Byrne’s Under the Dragon’s Tail. Byrne also directs the quartet of one-acts that are not always in perfect harmony, but as a quadriptych, they intriguingly show the ways in which elements of mythology, metaphor, and symbolism can give order to the chaos of the contemporary world.

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

Tennessee Williams’s Cat on a Hot Tin Roof features roles that are (pardon the expression) catnip to adventurous actors. This land mine of a play premiered in 1955, a year that, in retrospect, seems the apex of Williams’s success. The playwright’s career took off with The Glass Menagerie in 1945, followed by A Streetcar Named Desire in 1949, and continued for 28 years after Cat, until his death in 1983. During a long literary decline, he wrote a number of lesser, though admirable, plays, but even the best of those don’t measure up to his depiction of the Pollitts, a clan of nouveau riche Southern strivers squabbling over “twenty-eight thousand acres of the richest land this side of the valley Nile.”

Sex, Grift and Death

Potomac Theatre Project’s Sex, Grift and Death, an evening of one-acts by British playwrights Steven Berkoff and Caryl Churchill, captures the brutal nature of sex, financial survival, death, and illness. The lively cast uses a mixture of British and American accents that work for the sensibility of each piece.

Mister Miss America

Neil D’Astolfo’s Mister Miss America provides many pleasures beyond its nifty title, even though the material treads some pretty familiar ground. In the solo show, the beauty pageant obsessions of gay hero Derek Tyler Taylor (D’Astolfo) take center stage. DTT wants to share the story of his attempt to break the gender barrier at a beauty pageant in southwestern Virginia, where the contestants mostly hail from obscure burgs, such as Bristol, Galax, Martinsville and Radford, and the announcer uses descriptions like “She’s hotter than your pappy’s pistol!” as an introduction.

Reverse Transcription

For theater aficionados, the summer visits of Potomac Theatre Project to the Atlantic Theater are bracing—weighty pieces rather than fluffy fare. British writers, often well-represented, comprise one evening this year, but two American plays comprise the second. A revival of Dog Plays, a 1989 one-act with snapshot scenes that focus on the AIDS crisis, is by Robert Chesley, who wrote it after receiving “the diagnosis.” (He died in 1990.) It has been dusted off and paired with a new play, A Variant Strain, by writer-director Jim Petosa and Jonathan Adler, that is indebted to the older work.

Richard III

In William Shakespeare’s Richard III, the title character is a hunchback whose anger is fueled because he feels like an outcast. His quest for power becomes a form of revenge. Under Robert O’Hara’s direction, Richard III for the Public Theater is loose and playful. Actress Danai Gurira, in the gender-swapped title role, is sinewy and tiger-like. As Richard, she pounces, manipulates, smiles, grins, and grimaces: a shape-shifter who manipulates others.

Hamlet

“If a work is quite perfect,” wrote W.H. Auden about Hamlet, “it arouses less controversy and there is less to say about it.” Across four centuries, critics have found plenty to discuss in this longest of Shakespeare’s plays (also one of his most frequently performed). Auden is prominent among those viewing it as severely flawed. Director Robert Icke has joined the colloquy with an absorbing stage production, now at the Park Avenue Armory, that handles the script’s ostensible defects with aplomb and, in so doing, refutes T.S. Eliot’s suggestion that Hamlet is an “artistic failure.”

Epiphany

Anybody who remembers the 2000 Broadway musical adaptation of James Joyce’s The Dead would not be surprised to learn that Joyce’s story inspired Brian Watkins to write Epiphany. The productions look similar: set in a somberly lit room with a large rug in the center, a piano off to one side and multiple tables around. And in Epiphany, just as in The Dead, a group of people gather for a wintertime party in the home of someone named Morkan.

Chains

Elizabeth Baker wrote her first full-length play, Chains, at 32, and after it premiered in London in 1909, critics hailed a “new playwright of unmistakable dramatic genius.” But despite many plays that followed, success in London did not come again for Baker. And so Chains fits into the Mint Theater Company’s mission to “find and produce worthwhile plays from the past that have been lost or forgotten.” That mission is fulfilled in remarkable fashion in director Jenn Thompson’s lucid, moving, and exquisitely acted production, which feels both grounded in a specific historical and cultural milieu and yet also relevant today.

Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom

James Joyce’s Ulysses is a brilliant but dense and sometimes inaccessible work. Aedin Moloney’s solo performance in Yes! Reflections of Molly Bloom is adapted from Molly's “Yes!” soliloquy at the end of Joyce’s novel. Co-created by Moloney and acclaimed Irish author Colum McCann, the show is a remarkably ambitious collaboration, a welcome contribution to understanding the complexities of Molly Bloom (wife of Ulysses’ protagonist Leopold “Poldy” Bloom), and a consummate one-woman show.

The Orchard

After squandering her inheritance as an expatriate in Paris, Lyubov Ranevskaya, protagonist of Anton Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, comes home to Russia to discover that the old order, so favorable to the haute bourgeoisie, has been scrambled by burgeoning social mobility. Unable to meet the carrying charges on the family estate, Ranevskaya (Jessica Hecht) and her brother Gaev (Mark Nelson) dither rather than addressing the double whammy of altered personal circumstances and a transformed national culture.

Soft

At its core, Donja R. Love’s powerful drama Soft has a certain familiarity. It is a variation on The Blackboard Jungle or Up the Down Staircase—but with a more ruthless, 21st-century demeanor. Its teenage characters have moved beyond the troubled inner city to incarceration, and their mentor has a darker past than either Glenn Ford or Sandy Dennis’s characters, respectively, in those films. In this facility, students wear prison jump suits and are part of a correctional program designed to save them from a criminal career—or is it?

Mr. Parker

In the 1950s Paddy Chayefsky wrote a successful drama, Middle of the Night, in which nobody could understand what a young Gena Rowlands could see in an old Edward G. Robinson. Or, in the movie version, what Kim Novak could see in Fredric March. That quandary is back, after a fashion, with Mr. Parker, Michael McKeever’s sort-of-new drama (it premiered in Florida in 2018). Only this time it’s hard to see what Davi Santos sees in Derek Smith.

Jews, God, and History (Not Necessarily in That Order)

Can an atheist serve as a guide to the history, customs, and longevity of the Jewish religion and its adherents? Moreover, how can an atheist recognize that a man who has just died is with God? At first glance, this seems quite absurd. Yet neither for Michael Takiff nor for his audience does it appear to be a problem. Jews, God, and History (Not Necessarily in That Order), Takiff’s one-man show, is a roller-coaster ride through Jewish belief, identity, and practice.

Three Sisters

It seems to never be a bad time to stage Chekhov’s Three Sisters: timeless and timely, funny and devastating, remarkably in tune with the currents of real life, and providing material for great actors to explore memorable and fully rounded characters.

Belfast Girls

In the 1840s, famine devastated Ireland, and approximately 1 million people died during the period known as the Great Hunger (An Gorta Mór in Irish). Another 2 million emigrated from the comparatively small island nation, and as a result, by 1852, the country had lost approximately 25 percent of its total population. Jaki McCarrick’s Belfast Girls, currently running at Irish Repertory Theatre, examines the effect the famine had on women in particular and explores its devastating impact on the poorest of the poor in Ireland.

New Golden Age

Time and again, stories about what the future holds for technology and humanity have enthralled audiences—think of the rabid followings for The Twilight Zone and Black Mirror, produced 50 years apart. Playwright Karen Hartman puts forth her contribution to the genre with New Golden Age. But whereas those TV shows grabbed viewers with suspense, plot twists and amusing allegory, New Golden Age mainly offers talking. More than three-quarters of its run time is occupied by one long scene, and it consists mostly of people standing around talking. That tedium outweighs any emotional reaction that Hartman’s Facebook-run-amok scenario may elicit.