Bernard and Rory, the only characters in Erin Mallon’s The Net Will Appear, are next-door neighbors in Toledo, Ohio. Bernard is a curmudgeonly 75-year-old with a penchant for bird-watching. Rory, age 9, is a wiseacre whose chatter is laced with malapropisms and bawdy phrases she doesn’t understand fully.

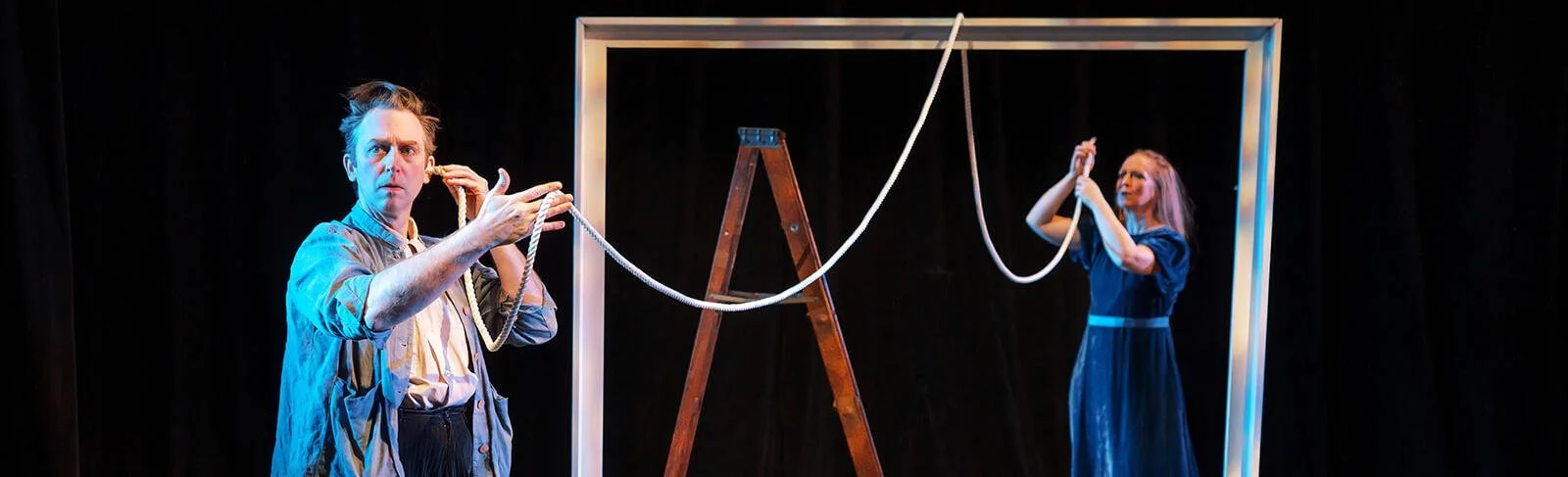

Eve Johnson as Rory in Erin Mallon’s The Net Will Appear at 59E59 Theaters. Top: Richard Masur as Bernard. Photographs by Jody Christopherson.

The play opens with the characters’ first encounter—contentious and funny, with a promise of dramatic fireworks to follow. The two are on adjacent roofs, seeking sanctuary from family life. Bernard (Richard Masur) craves solitude; Rory (Eve Johnson), who’s never inclined to silence, tries repeatedly to engage Bernard with her juvenile brand of badinage.

Bernard is an Episcopalian with a drinking problem. He’s polite, though sometimes impatient; and he keeps his own counsel. Rory is a Jewish student at a Roman Catholic grade school. Her conversation is unfiltered. “Everyone thinks you’re a psycho,” she informs Bernard. The odds appear slim that these dissimilar souls can find common ground. In situation comedies of this ilk, though, strange bedfellows inevitably end up best friends.

Before the first scene is over, it’s evident that under its veneer of comic palaver, The Net Will Appear is a melancholy study of youth and age. “I don’t have much past and you don’t have much future,” Rory informs Bernard with a child’s unwitting cruelty. As the action progresses through the seasons of a year, Mallon introduces themes of social importance—most notably, the kinds of anguish suffered nowadays by the youngest and the oldest in American society.

Rory—a child of divorce who seldom sees her father—feels uncertain and out of place in the household her mother has established with a new husband. Rory’s mother is suffering from postpartum depression; the stepfather is egotistical; and a new half-sister is usurping all the affection the family can muster.

Bernard is principal caregiver for his wife, Irma (one of the play’s several offstage characters). Irma’s personality is being leached away by dementia; and Bernard grieves for the loss of his adored companion while attending to the remnant of her that hasn’t been extinguished by Alzheimer’s disease.

Mallon’s script is efficiently constructed and poignant, but there’s little verisimilitude here. The dramatic situation is contrived; the characters are fabricated rather than observed; and the dialogue rises only intermittently above the glossy superficiality of 1980s television comedy. According to formula, the play’s strange bedfellows come to appreciate, even love, each other. Rory’s innocence awakens Bernard’s paternal instincts and, under his tutelage, she becomes sensitive to the wonders around them. “First robin sighting of the season,” he says. “Look at that beautiful red breast.” (Rory, who thinks “breast” is a dirty word, is mightily titillated by that remark.)

Masur in the monologue that is the emotional high point of The Net Will Appear.

While Rory’s guilelessness ultimately endears her to Bernard, the play’s spectators are likely to respond with varying degrees of tolerance for the cute-as-pie dialogue Mallon has concocted for the little girl. The topical references that punctuate Rory’s comic patter are particularly irksome. Take, for instance, the wacky names she gives her possessions: a favorite doll is called Netflix, her cat is Dr. Phil, and the bathtub is “Harriet Tubman.” Like so much else in The Net Will Appear, these jokes, with their transitory shelf life, are disposable.

What’s most satisfying about this production is Masur’s distinguished performance. Renowned for character roles on Broadway, in movies, and on television, Masur makes Bernard’s grief-stricken monologue about his wife’s vanishing personality the most authentic and memorable sequence of the play. Undeterred by W.C. Fields’ warning that actors should “never work with children or animals,” Masur gives a touching performance, enhanced by evident empathy with his younger co-star but never upstaged by her undeniable (for want of a better word) cuteness.

The Net Will Appear takes place entirely on the rooftops of the two houses. Scenic designer Matthew J. Fick has supplied a realistic, eye-appealing set, with the roofs separated by a space at center stage that’s supposed to be too wide for either character to jump across safely. Each actor is confined to his or her roof throughout the 80 minutes of the performance. That spatial separation is a tough assignment for players who’re supposed to depict affection that escalates scene by scene. Mark Cirnigliaro’s capable direction minimizes the awkwardness of all that distance, but direction can’t transform counterfeit dialogue into dramatic gold. What saves the day is Masur’s virtuosity, which redeems a predictable comedy-drama and makes the joyous final scene soar like one of Bernard’s beloved songbirds.

The Net Will Appear runs through Dec. 30 at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St., between Park and Madison). Evening performances are at 7:15 p.m. Tuesdays to Saturdays; matinees are at 2:15 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays. For information and tickets, call (646) 892-7999 or visit 59e59.org.