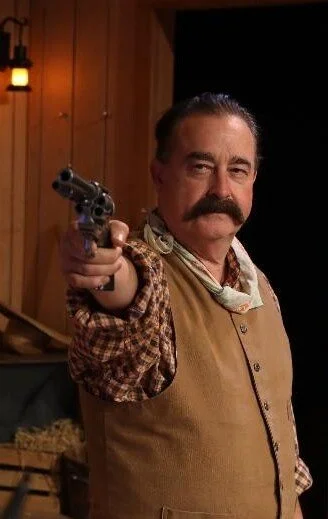

Leighton Samuels (left) plays Ransome Foster, and Daniel Kornegay is Jim “The Reverend” Mosten in a revival of Jethro Compton’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance at the Gene Frankel Theatre.

Jethro Compton’s stage adaptation of the classic short story The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance delivers a taut and compelling drama that both honors and subverts the conventions of the Western. Directed with precision and emotional clarity by Thomas R. Gordon, this new production retains the story’s essential moral conflict—between truth and legend, justice and lawlessness—but deepens its resonance by introducing a new character and themes that can speak powerfully to a modern audience.

Derek Jack Chariton plays the title character in a stage version of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, based on the short story made famous by John Ford’s 1962 Western.

Dorothy M. Johnson’s original 1949 story is a spare, morally ambiguous tale that strips away the romantic veneer of the American West. (The story was the basis for the 1962 John Ford film starring James Stewart and John Wayne, with Lee Marvin in the title role, in which a newspaper editor utters the memorable line: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”)

At the story’s heart is Ransome Foster (Leighton Samuels), an Eastern tenderfoot in the 1800s searching for the fabled West. A victim of a violent encounter with Liberty Valance (Derek Jack Chariton) on the outskirts of the frontier town of Twotrees, he is brought unconscious by local rancher Bert Barricune (Samuel Shurtleff) to the safety of the town saloon, run by Hallie Jackson (Mari Blake). Suffice it to say, Foster, armed only with books and principles, becomes a living symbol of how civility falters in the face of unchecked brutality.

The story’s power lies in its refusal to glorify violence and its unflinching depiction of how myths are made and truths quietly buried. Compton’s 2014 adaptation maintains this central arc but infuses it with fresh urgency by adding a new character, Jim “The Reverend” Mosten, a saloon worker and aspiring preacher. Played with vulnerability and conviction by Daniel Kornegay, Jim becomes a vital emotional presence in the story. His optimism, humility, and deep sense of justice contrast starkly with the cynicism and fear that haunt the town. His friendship with Foster and Hallie—the play’s central love interest—provides moments of warmth and levity that underscore the stakes of what is to come.

Jim, though open-minded and generous-hearted, still knows that racism runs deep in Twotrees:

The people don’t want to hear the Lord’s voice from a Negro. Round here, a man like me is meant for scrubbin’ floors.

Inevitably, Valance and his gang inflict an outrage that leaves Hallie grief-stricken—it’s a harrowing moment that nearly eclipses the final showdown between Foster and Valance.

“The story’s power lies in its refusal to glorify violence and its unflinching depiction of how myths are made. ”

The performances are uniformly strong. The idealistic scholar-teacher Foster is rendered with the right balance of vulnerability and moral conflict by Samuels, while Blake’s Hallie emerges not just as a romantic foil but as a woman caught between survival and sorrow. Shurtleff’s Barricune, who is also a gunslinger, is a strange mix of Good Samaritan, unrequited lover, and arrogant sharpshooter. Chariton’s Valance is a snarling relic of the Old West, with Ben-David Carlson and Dillon Collins playing his two “mongrels,” who carry out his bloody instructions. And Scott Zimmerman portrays Marshal Johnson as the very image of authority—undermined by his inability to enforce it.

Nino Amari’s set design is spare but effective, relying on shadow, light (lighting by Reid Sullivan), and subtle sound design to evoke the loneliness and tension of Twotrees. While the Prairie Belle saloon isn’t fancy—its interior shows a bar with stools, small round table with chairs, upright piano, and wooden floor—it reveals character with its hanging candelabra and a horseshoe nailed over each door.

Samuel Shurtleff plays a gun-toting rancher named Bert Barricune in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Photographs by Joshua Eichenbaum.

Although Foster is the protagonist who goes from the proverbial rags to riches in the story, by weaving Jim Mosten into the fabric of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Compton has created more than a retelling; it is a reinvention. The result asks one to reconsider who gets to participate in the making of history and at what cost.

In the end Compton does not abandon Johnson’s original question—who really deserves credit for killing Valance, and what does that truth say about American ideals?—but rather reframes it through a more expansive moral lens. This narrative shift also gives the production a powerful emotional gravity. It transforms the Western from a genre often associated with rugged individualism and frontier justice into a vehicle for collective reflection on who matters in America. And, in a cultural moment increasingly attuned to whose stories are told and whose are ignored, this revival feels urgent, necessary, and powerfully alive.

The Onomatopoeia Theatre Company’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance plays through July 26 at The Gene Frankel Theatre (24 Bond St.). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesday through Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. on Sunday. For tickets and more information, visit theonomatopoeiatheatrecompany.com or genefrankeltheatre.com.

Playwright: Jethro Compton, based on a short story by Dorothy M. Johnson

Director: Thomas R. Gordon

Set: Nino Amari

Lighting: Reid Sullivan

Costumes: Susan Yanofsky