Move over, James Brown. It’s time to add Joe Morton and Dick Gregory's names to the pantheon of hardest-working men in show business. In Turn Me Loose, written by Gretchen Law and directed by John Gould Rubin, Morton gives a tour de force performance as Gregory, the tireless civil rights activist and stand up comic known for his acerbic social satire on race and American politics.

Morton, of the hit TV show Scandal, adeptly captures both the younger and the older Gregory as the play moves back and forth in time. As a comedian, Gregory eloquently holds a mirror up to the contradictions in American society. Although he believes economics are at the root of many problems in society, he contends that “poverty is not the worst disease on earth. Racism is.”

Born in 1932, in St. Louis, Gregory says he had “black assets: fast feet, and a fast tongue.” He was athletic and outspoken, and when he was given a three-year contract at Hugh Hefner’s Playboy Club in Chicago in 1961, he was catapulted into another realm as an entertainer, not as a “shuffling minstrel, but as a 28-year-old star.” However, he often stepped down from comedy to take up the cause of the 1960s civil rights movement and march side by side with Medgar Evers.

Morton captures the conflict between being a performer and being an activist that caused Gregory to take pause at moments in his life. In a chilling moment, the young activist gets a bad feeling that he can’t shake before heading back down South to join Evers. But suddenly his son dies and he returns North to join his wife. Only two weeks later, Evers is assassinated; Gregory believes his personal tragedy spared his life. The dangers of activism and being a black man in the South in the ’60s were never more apparent. He realizes that the "racist system is nothing but a shadow. You got to dive through—every day could be your last.” He also realizes that bigotry is like the barb of an arrow piercing the skin. Gregory returns to comedy and aims, not so much to extract the arrowhead from the sides of American racists, but to shake them with enough laughter that it will fall out.

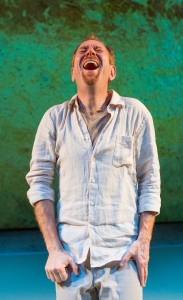

Morton’s voice has a deep timbre, and he has amazing reserve and control over both his voice and physicality. Often, while the tempo and volume rise, his body is restrained and still. Near the finale, sweat pours down his face, and instead of taking the handkerchief, as he does at times throughout the play, he forges through what he has to say: the power of his words is amplified by the apoplectic state of his face.

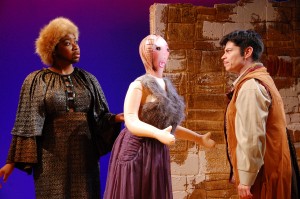

The raw immediacy of Morton’s performance, coupled with the power of Gregory’s message, incites some members of the audience to murmur “Mmm-hmmm” and “Yeah,” as if they are receiving a message from the pulpit rather than the stage. Also helping tell the story in a variety of roles is John Carlin; among other things he plays a bumbling mediator at a loss for words when Gregory delivers an acerbic diagnosis of the state of economics and its effect on all that ails American society.

It takes tremendous courage and intelligence to design and deliver the kind of comedy Gregory does. At 83, he's still going strong. Because of his work with the civil rights movement, and the way in which he has relentlessly, with humor, grace and a tongue like a sword, dissected the contradictions about race in America, the conversation itself has since taken a few twists and turns. For instance, Vin Diesel, who rose to stardom in The Fast and Furious films, declines to accept any racial pigeonhole. Rather, says one observer, Diesel presents himself as “a multiethnic Everyman.” The actor’s insistence on identifying himself as a human being, rather than by race, is an important step. As Turn Me Loose makes plain, it’s one that Dick Gregory has worked tirelessly for.

Turn Me Loose plays at the Westside Theatre (407 West 43rd St.) through July 3. Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday, at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday, and at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and at 3 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $79 and may be purchased by calling (212) 239-6200 or visiting www.turnmelooseplay.com.