In the NewsCorp world, an ever-present Murdoch (Jamie Jackson) can appear and exert his influence in multiple places simultaneously.

Anonymously penned scripts are rare—and rarer still when the identity of one of its two characters is obscured. In Murdoch: The Final Interview, a multimedia drama/farce directed by Christopher Scott, that actor portrays both an enigmatic interviewer and media magnate Rupert Murdoch.

Murdoch (Jamie Jackson), a stooped nonagenarian, is interviewed by Chodrum Trepur, the “mystery man.” Despite his age and diminishing strength, Murdoch refuses to cede control of his media empire and remains powerful, untouchable. He can make or break world leaders, and as a “dirt digger” he can destroy his enemies by revealing their secrets in his publications. No wonder anyone taunting Murdoch about his blatant violations of journalistic ethics, or his ongoing longing for his father’s approval and mother’s warmth, would seek anonymity. The anonymous playwright must dodge Murdoch’s fury. Jackson, as both Murdoch and Trepur, is both a needy child, a relentless merchant of sleaze, and his own tormentor, respectively.

Murdoch shines a light to reveal his assailant. Photography by Russ Rowland

At the outset, Trepur reminds Murdoch of his meteoric rise to news dominance, from heir to a single paper to a multimedia mogul. Murdoch purchases failing papers and makes them profitable by filling them with scandal, pornographic titillation, and virulent political advocacy. (Andy Evan Cohen’s photo-by-photo projections document how the NewsCorp empire rests on a foundation of sensationalism and prurient smut.)

The synchrony of Cohen’s work and Josh Weidenbaum’s sound recordings poignantly underscore what may be Murdoch’s most egregious abuse of power—the News of the World phone-hacking scandal. Yes, Murdoch may be culpable even if he doesn’t directly order his editors to hack and publicize intimate details of elites’ personal lives and only turns a blind eye to invasion of privacy.

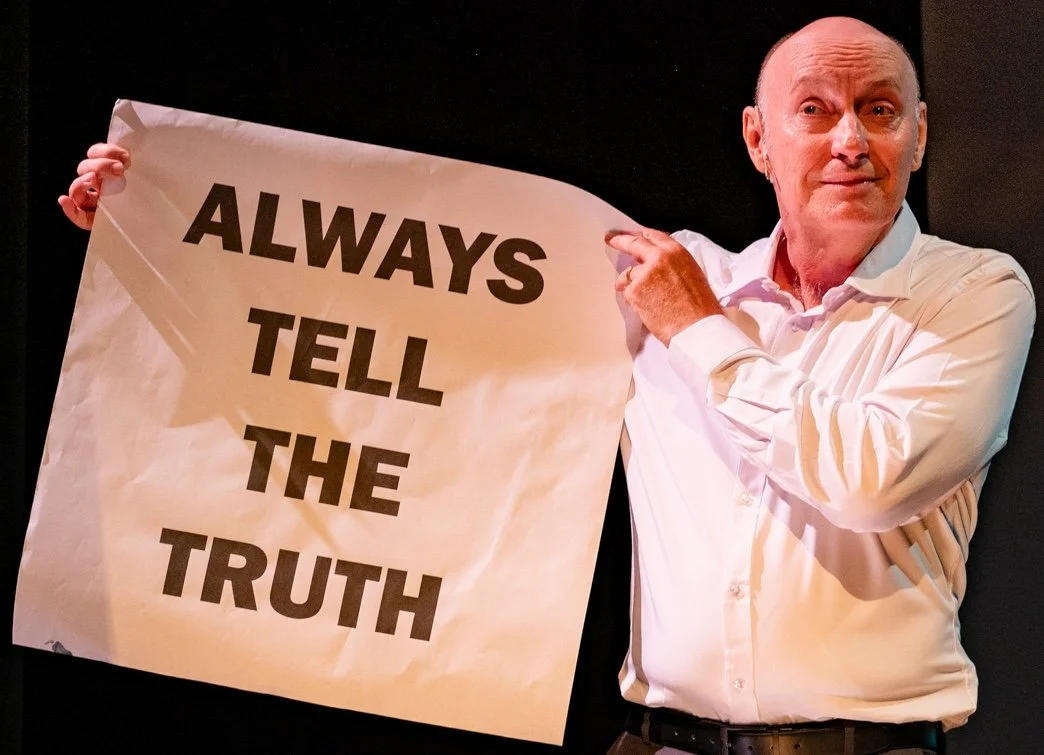

Murdoch displays his mother’s dictum, one he touts but doesn’t follow.

When the Cohen/Weidenbaum audiovisual montage dovetails with the voice of teen murder victim Milly Dowler’s frantic mother, News of the World’s phone hacking reaches a new low. A crime scene and a cemetery are projected behind Trepur; Mrs. Dowler cries out to husband John that Milly’s voice messages have been checked. Milly must be alive, Mrs. Dowler maintains, unsuspecting that her daughter’s phone has been hacked, and a murder investigation obstructed.

Jackson’s Murdoch possesses little insight and less remorse. When a female interviewer, whose voice is projected, asks if he enjoys power, he says yes, but it comes with responsibility:

The important thing is that there be plenty of newspapers with plenty of different people controlling them so that there’s a variety of viewpoints, a choice for the public.

Of course, this variety never happens in Murdoch’s media holdings.

Anyone who stares at Chodrum Trepur’s name on the backdrop will, before long, realize that it is just Rupert Murdoch spelled backward. Is Chodrum then Murdoch’s conscience, as he suggests? Is he a moral foil? This is the real mystery. Chodrum’s only disclosure is that he worked for Murdoch.

Murdoch and his alter ego Chodrum may be two sides of the same person.

As both Murdoch and his alter ego, Jackson shines. He is equally at home when he switches from his native Aussie accent to Trepur’s nonspecific American dialect. Even more extraordinary is Jackson’s physical transition from Murdoch, with his twisted, scrunched up face, bent-over gait, and self-absorbed demeanor, to Trepur’s confident and almost tortuously mocking poses.

Peter R. Feuchtwanger’s efficient, multipurpose set includes a tall, stationary ladder (which Murdoch the child regularly ascends to impress his father) and a comfortable, informal downstage talk-show set-up, where Trepur sips from a mug, effortlessly prompts Murdoch with often provocative questions, and leaves his chair to make way for his interviewee to sit and respond. (After all, they are only one person, playing musical chairs).

An open, multipurpose upstage area provides a venue for Murdoch, where he is aided by a mute female in various outfits. As a physician in a nursing facility, she attends to a very elderly and delusional Murdoch. It is the on-screen projections and videos, though, that provide the most compelling arguments and illustrate the hellish way in which Murdoch acquires and maintains his media empire.

One wonders whether Murdoch’s biggest dilemma, and the one that Trepur saves for last, is that the aging mogul is forced to confront his own nearly monstrous mega-creations, his own mortality, and resolve his own fractured family relations and plan of succession. It’s an unenviable dilemma, and we are left wondering who is more despicable—the billionaire magnate, or the driven whistleblower, who casts Murdoch’s misdeeds (which, as Chodrum Trepur, may be his own) into the public’s consciousness.

Murdoch: The Final Interview runs at Theater 555 (555 West 42nd St.) through Dec. 28. Performances are Tuesdays through Saturdays at 7:30 p.m.; matinees are at 3 p.m. on Sundays. For tickets or more information, call (646) 412-2277 or visit murdochthefinalinterview.com.

Playwright: Anonymous

Director: Christopher Scott

Lighting Design: Saunders Harrison-Matthews

Set Design: Peter R. Feuchtwanger

Sound Design: Josh Weidenbaum

Projections & Video Design: Andy Evan Jones

Music: SoHee Youn