Tami Stronach began her career playing the Childlike Empress in The NeverEnding Story (1984). However, she followed the screen credit by pursuing dance. While dancing full-time on her toes, she started to miss theater so her next move brought her back. Fortunately, acting chops didn’t have to suffer the lift her high step always gave her. As part of Flying Machine with several friends, this company approached theater though movement, and for seven years, she stayed connected to both disciplines before folding. But the members eventually realized they missed each other, and coalesced movement around providing high quality theater for families. The formation of Paper Canoe would coincide with a New Victory Theater LabWorks program seeking plays for children and resulted in a production that “sucks the light out of the theater,” according to Stronach, who choreographed the play and stars as the lead character Moth. OffOffOnline: So does Light, A Dark Comedy have everyone in the dark, bumping into each other?

Stronach: No, the play is well lit. The audience can see everything. It’s the language of the play. But the premise is the sun has been stolen and forgotten. We’re trying to show how quickly history can vanish, and the importance of keeping stories alive.

OffOffOnline: Who stole the sun and why?

Q&A: Stronach’s Choreography Drives ‘Light, A Dark Comedy’

Stronach: The world was constantly lit and everybody worked all the time. This meant everything was go-go-go, and people never saw their children. At the same time, the space for reflection and dreaming got sucked up into this constant, bright, manic whirlwind. So an inventor tried to bring balance by creating a dark maker and ended up stealing the sun. The world was left in the dark, and Moth, my character, is trying to bring it back.

OffOffOnline: Where did this idea come from?

Stronach:We were brainstorming, and our director (Adrienne Kapstein) just said, “what if we created a world where there was no light.” We decided that was near impossible. But the impossibility intrigued us. Then Greg Steinbruner, Robert Ross Parker and I went on a writer’s retreat. We covered the wall with Post-it Notes and came up with the first two acts. But eventually Greg made revisions and completed the end. On the other hand, this is physical theater. So the story was written as we improvised things in rehearsal. We would then go home, and write what they saw. So the relationship between image and text was very organic and fluid. This amounted to a play written by a choreographer, a writer and a physical theater artist—providing all these different entry ways into the drama. Then last year Greg Steinbruner rebuilt the script into what it is now with the help of dramaturge Jeremy Stoller. Ultimately our goal as a company is to produce work that is as rich in narrative and text as it is invested in creating visual poetry.

OffOffOnline: Can you describe this world a little more?

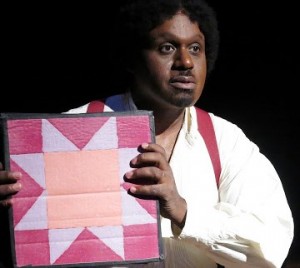

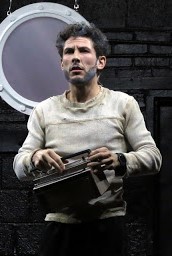

Stronach: The actors wore a headgear called dim makers, which helps them see, and the city functions on a grid of hooks and ropes so people don’t get lost. It’s sort of like the trolley system in San Francisco. But acts as a metaphor for staying inside the box and not questioning the way things are. As a result, adults might contract “the sleep,” where they enter into a dream state and never come out.

OffOffOnline: How does Moth figure into all this?

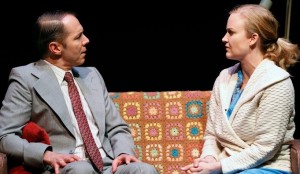

Stronach: She unplugs from the grid, and goes off into the darkness where she meets a boy who has lived his whole life alone. Figuring out all these genius mechanisms for surviving, they then meet Sunny and Ray who have created a clandestine radio show. From their platform, the duo pretends to be on a beach and have gone into complete fantasy to deal with the problem. So they sit around and pontificated about the sun without doing anything about it. But the idea is to have characters with flaws and together there’s enough inertia and alchemy to achieve the things that shift society.

OffOffOnline: The play is billed as a little scary? Do parents have to worry?

Stronach: Well, it’s a mix. There’s a lot of humor, but I think losing your mom in a black void would be scary for a 4-year old. An 8-year old, on the other hand, should be fine and doesn’t mind being a little scared—especially since we have a happy ending.

OffOffOnline: What was the challenge of writing for children and adults?

Stronach: People underestimate the intellect of kids. They come into the theater with fewer assumptions and are more willing to be carried away by the story. So the story can reach audiences of all ages.

OffOffOnline: Finally, what message are you conveying about breaking free from your parents’ worldview?

Stronach: Moth doesn’t accept the gloomy truth she’s supposed to accept, and she changes the world. So I want my daughter to believe that she has the strength to find solutions that my generation didn’t think of.

Read Ray Morgovan's review of Light, A Dark Comedy here.

Light, A Dark Comedy runs until April 10 at the Triskelion Arts Muriel Schulman Theater (106 Calyer St. between Clifford Pl. and Banker St.) in Brooklyn. Matinee performances are Saturday and Sunday at 10:30 a.m. Tickets cost $18. To purchase tickets, visit www.papercanoecompany.com.