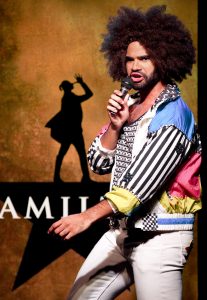

As the saying goes, “One man’s trash is another man’s treasure.” So it is in Storage Locker, a black satire riffing on A&E’s reality show Storage Wars. Written by Jeff Stolzer, the play is often quite funny, with expressive banter between a husband and wife who secure the winning bid on an abandoned storage unit. Stolzer is a clever writer. In Storage Locker he develops interesting and layered characters, intricately weaving them into shifts in time. Bryn Packard and Nicole Betancourt, who play the husband and wife, deliver the dialogue with velocity of a couple that have been together for awhile. Stolzer easily takes them from ridiculing each other to playful and loving in a blink. Betancourt is smart and sassy, a diminutive “spitfire” to Packard’s “I’m the provider, I make the decisions” husband. They are believable and engaging.

Director Julián Mesri invests the script with a tempo that draws the audience in. With a video camera on a tripod and monitor, soon enough it becomes evident that the pieces of masking tape on the floor are marks to make sure the actors are in the sight line of the camera for television production. Reality television has little to do with reality, after all. Here, the audience is inventively caught between observing the actors on stage and through the monitor. Betancourt and Packard have a great time playing to the camera; their chemistry is contagious. Mesri’s use of the stage, including the sound booth and emergency stairwell, as well as video camera equipment, helps creates a comic romp through one man’s trash.

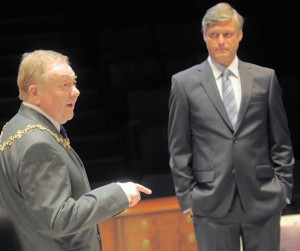

Also watching the monitor is an older man seated with his back to the audience. He fiddles with a Rubik’s Cube. In time, the older man (David Crommett) enters the fray, wanting to purchase the storage unit from the husband and wife. He claims he was late to the auction because of a doctor’s appointment. Crommett plays the character in the manner of a master manipulator. He toys with both the husband and wife, luring one with his tales of woe and the other with the wisdom he has developed over 30 years of choosing which storage units pay off. That might be a Picasso behind the trunk. Again, the fun of Mesri’s direction is watching the actors running to the sound booth as if to engage the television producers for direction or utilizing the camera as a handheld and chasing the old man.

Stolzer’s script, with an ample amount of intrigue, and Mesri’s keen staging keep everything moving smoothly until the last five minutes, when it all just sputters. Oddly, with everything that’s going for it, the play devolves at the very end into a confusing “fade to black” puddle. Even the actors, who until this point were spot on, appear lost. Throughout the play the storyline arches and pulls back, reels and sways, and then, suddenly, it’s as if someone lost the last two pages of the script—65 minutes of witticisms, laughter, cajoling, and get-rich-quick banter followed by five minutes of “What just happened?”

The set design by Warren Stiles looks all wrong, and a simple site visit to Gotham Mini Storage should have been required. Instead of a storage facility of cement hallways and orange metal roll-up doors, there is only black plastic sheeting, ragged at the bottom where it doesn’t come completely to the floor and light seeps under. Trash bags the characters pull from the storage unit that are supposedly filled with 50 pieces of clothing are kicked around as if they are filled with crumpled paper.

The lighting by Miguel Valderrama appears to toy with the otherworldly, in a Twilight Zone manner, but falls just a bit short. Most likely his efforts would have paid off with an appropriate set, but how does one light a misstep? Director Mesri put together an interesting original score, which included excerpts from Leos Janáček’s first and second string quartets.

Storage Locker is a perfect example of why small theaters are one of the best “play-grounds” for makers of theater. Playwrights get to test their writing skills, directors hone their craft, and actors perfect character development—all for the pleasure of the audience, which gets to bear witness to the creative process. For 65 minutes, or 92% of the time, Storage Locker and its quirky, delicious contents deliver.

Storage Locker can be seen at 8 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays and at 3 p.m. Sundays through Oct. 30 at IATI Theater (64 East 4th St., between Bowery and Second Avenue). The running time is 70 minutes. Tickets are $30; students and seniors $25. For more information and to purchase tickets visit iatitheater.org/programs/detail/storagelocker.