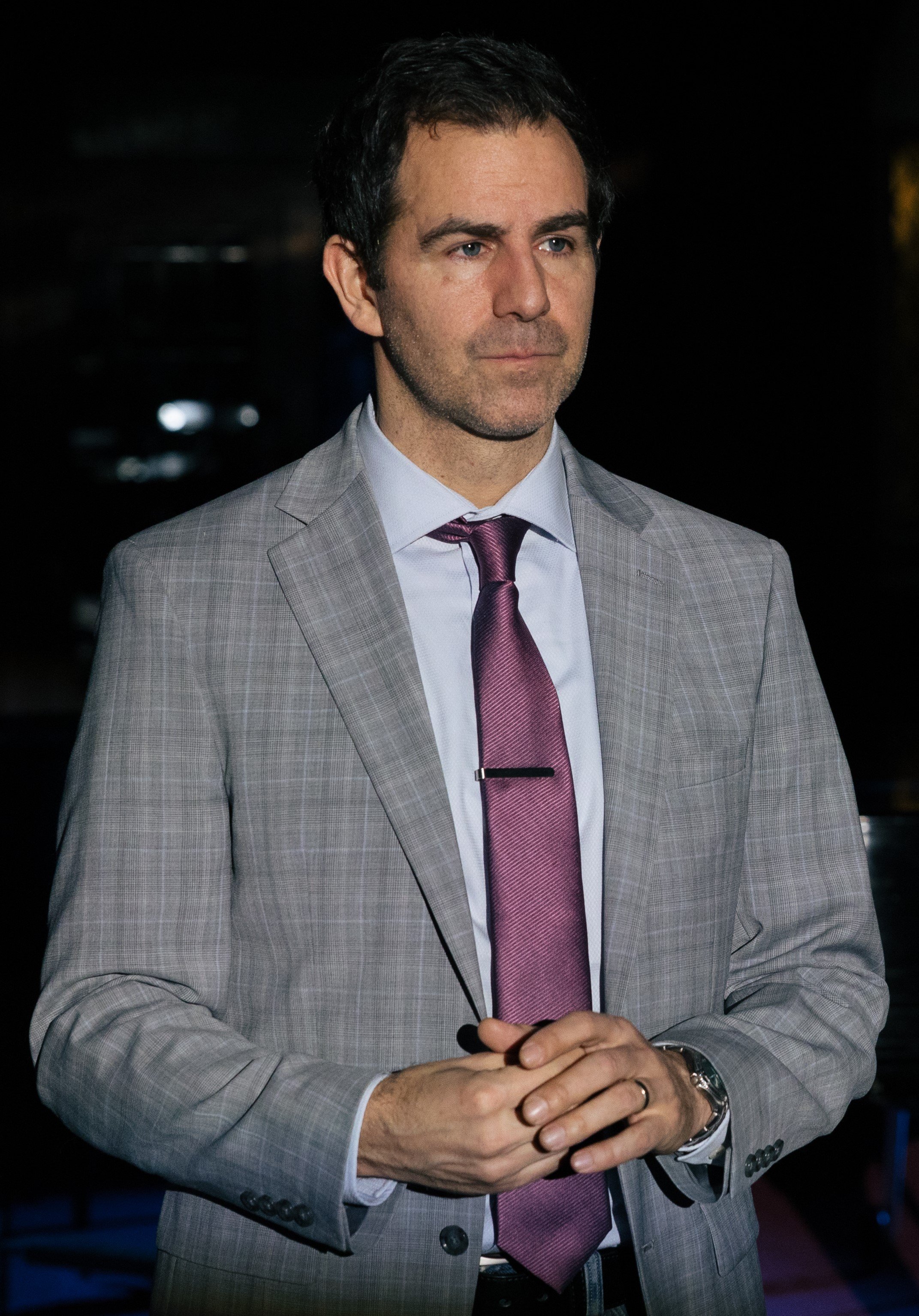

Len Cariou (right) as Professor Morrie Schwartz and Christopher J. Domig as Morrie’s former student Mitch Albom in the Sea Dog Theater revival of Tuesdays with Morrie.

Len Cariou—Stephen Sondheim’s original Sweeney Todd—plays the title role in Sea Dog Theater’s revival of Tuesdays with Morrie by Jeffrey Hatcher and Mitch Albom. Amid the stark, solemn beauty of Charles Otto Blesch and Leopold Eidlitz’s Romanesque-revival chapel at St. George’s Episcopal Church on Stuyvesant Square, director Erwin Maas has built a fleet, music-filled production around the distinguished Canadian actor, who’s sharp and feisty at 84. In the role of a professor experiencing the galloping effects of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease), Cariou steers clear of mawkishness with a performance that’s wry and witty from beginning to end.

The opening speech of this 2002 two-hander, based on Albom’s 1997 memoir of the same title, is spoken by Mitch (Christopher J. Domig), and it lays out the evening’s itinerary:

The last class of my old professor’s life met once a week in his house by a window in the study where he could watch a small hibiscus plant shed its leaves. The subject of the class was The Meaning of Life. … The class met on Tuesdays and had only one student. I was that student.

“When you learn how to die, you learn how to live,” Morrie tells Mitch. Photographs by Jeremy Varner.

If you’ve read Albom’s memoir, you’ll know that Morrie Schwartz, like that hibiscus, is fast approaching the end of his earthly cycle. With sure-handed stage technique, Maas and his actors rein in the multiple-hanky nature of the material. Late in the play, Morrie tells Mitch that “when you learn how to die, you learn how to live.” This production concentrates on the joys of living rather than the agony of death.

As a Brandeis University undergraduate, Mitch enrolled, pretty much by chance, in one of Morrie’s classes. Fired up by the brio of Morrie’s teaching, Mitch became a sociology major, took all the courses Morrie offered, and wrote a thesis under his direction. He also confided to Morrie that he wanted to defy his parents’ disapproval and become a professional jazz pianist; and Morrie counseled him to follow his heart rather than his parents’ insistence on law school.

Domig plays a harried, hypercompetitive sportswriter.

After graduation, Mitch lost touch with Morrie. He pursued jazz for a time, then obtained a master’s in journalism and became a sportswriter. Spotting Morrie interviewed on late-night television about the effects of ALS, Mitch contacts him. Morrie, age 78, is handling his illness with a calm reflectiveness that Mitch recognizes from their acquaintance years earlier.

When Mitch finally visits, Morrie is unsettled to find his former student harried, oversubscribed, and consumed with professional rivalry. Morrie casually proposes a “last class,” a weekly Socratic tutorial regarding what’s most worthwhile. Mitch accepts, flying from Detroit to Boston every Tuesday to converse about a variety of topics, such as the state of the world, emotions, family, money, self-pity, aging, regrets, death, forgiveness and, especially, love. When Morrie is clearly at the end of the line, the two discuss their notions of what would be a perfect day—and they say goodbye.

Maas’s direction of the play is frequently akin to choreography, and on a couple of occasions the actors execute actual, though casual, dance steps. This fanciful staging elevates the production above the naturalistic script’s prosaic dialogue; and the actors’ avoidance of melodrama deepens their characterizations.

Scenic designer Guy Delancey has placed a nine-foot grand piano at the heart of the deep, narrow playing area, leaving the rest of the space bare, with supplemental props introduced as necessary. In his sound design, Eamon Goodman handles the dicey acoustics of St. George’s monumental chapel with aplomb, avoiding echoes, reverberations, static, and other sound-system blowback.

Cariou (with Domig, left, as Albom) brings wit and a light touch to the role of Morrie, an ailing Brandeis professor.

Domig plays the grand piano, and does so expertly, at the beginning and at significant points in the narrative. Except for Ray Noble’s “The Very Thought of You,” specified in the script, all the melodies have been composed, or are improvised, by Domig. When Mitch returns to the keyboard near the end, after a long spell away from it, that action and the moody music Domig plays are a touching signal that the meetings with Morrie have revitalized Mitch’s emotional life, reshaping him with his mentor’s wisdom.

Near the end of his book, Albom writes, “Morrie, my old professor, wasn’t in the self-help business. He was standing on the tracks, listening to death’s locomotive whistle, and he was very clear about the important things in life.” The Sea Dog revival is a 90-plus-minute consideration—heartfelt but very funny—of what’s genuinely important. And, by the by, it’s an ideal pretext for contemplating the soaring architecture of a New York City landmark that’s still sometimes called “J.P. Morgan’s church.”

Sea Dog Theater’s production of Tuesdays with Morrie, playing at St. George’s Episcopal Church (209 E. 16th St., between Third Avenue and Rutherford Place) and scheduled to close on March 23, has been extended for performances from April 1 to April 20. During the extention, performances are at 7:30 p.m. Mondays through Saturdays (no performance on Wednesday, April 10). For tickets and information, visit seadogtheater.org.

Playwrights: Jeffrey Hatcher & Mitch Albom

Direction: Erwin Maas

Sets, Lighting & Costumes: Guy Delancey

Sound Design: Eamon Goodman