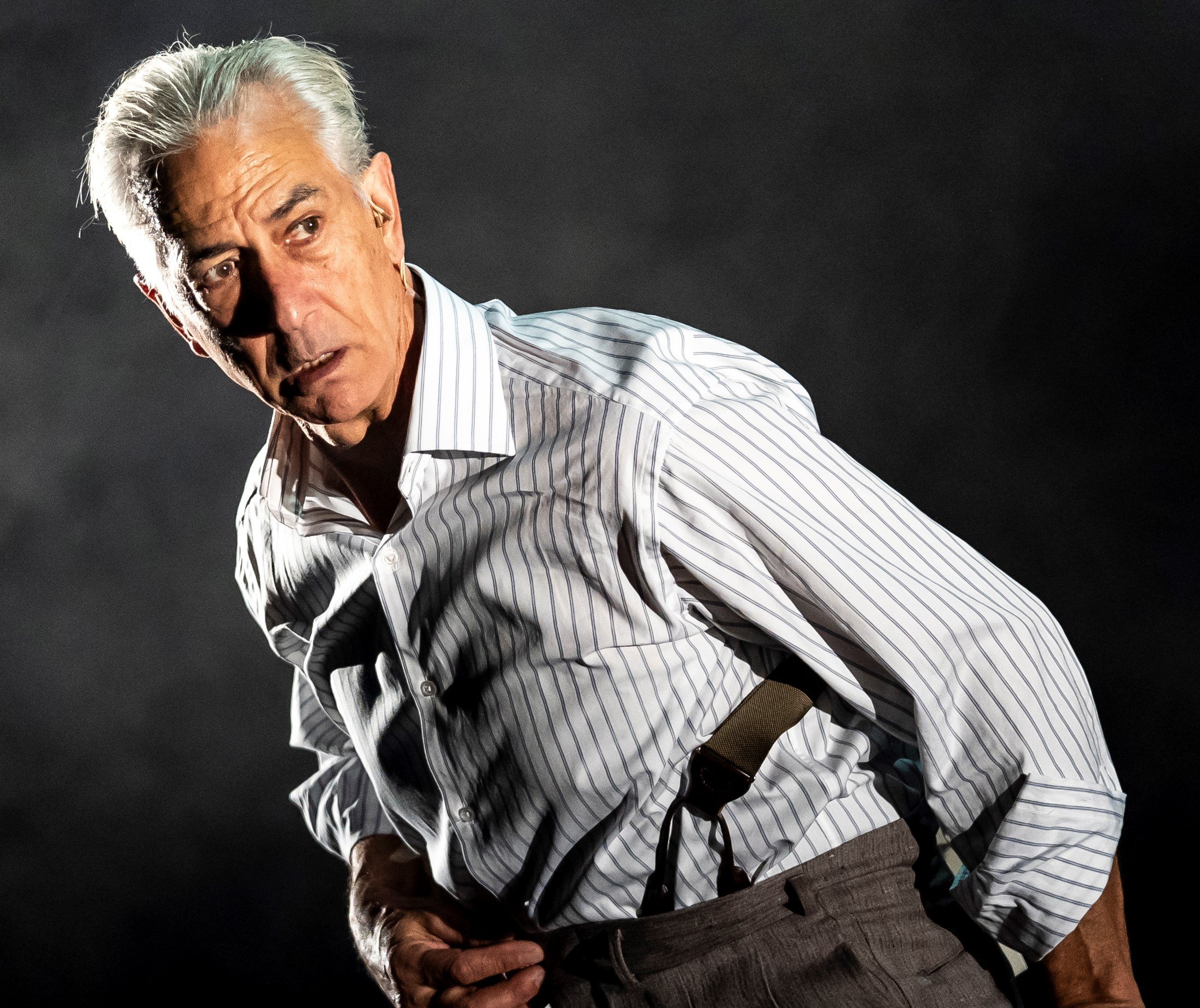

David Strathairn plays a Polish wartime hero in Clark Young and Derek Goldman’s Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski. This photograph and banner photo by Hollis King.

David Strathairn, whose stellar career as a character actor has spanned decades, gives a brilliant, riveting solo performance in Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski. Playing a Pole who experienced the Holocaust, he draws on historical evidence and the testimony that playwrights Clark Young and Derek Goldman employ in their portrait of a righteous and desperate man determined to prevent the annihilation of his country’s Jews. This is the real-life Karski, humble, modest, and painfully aware of what he could do, and more so of what he could not do, to save them.

David Strathairn as Jan Karski prepares to change clothes for his escape. Photograph by Rich Hein.

As a self-styled “insignificant, little man,” whose alternate identities included diplomat, spy, and humanitarian, Karski’s answer to the suggestion that he was a hero was a resounding, “Hero? No!” That is not the portrait that Strathairn paints. Although the play opens with footage of Karski preparing for his 1977 interview for Claude Lanzmann’s documentary Shoah—Karski is so overwrought that he leaves the room—the play clearly sees him as a hero. What defines him as such? Was it his extraordinary courage, a determination to do what few, if any, would attempt, the spontaneous rescue of someone or something from a tragic end, or all the above? Yet despite relentless efforts, Karski is thwarted. Have his efforts been for naught? Has he failed? Young and Goldman focus on the way Karski grapples with that dilemma.

To save the remaining Jews of Poland, Karski must gain both the support of the Allies and that of his own government-in-exile. He witnesses firsthand the dead and dying of the Warsaw Ghetto and the brutality of the concentration camps.

With extraordinary physical flexibility and an ability to react in split-seconds to a barrage of elements—enemy firepower, physical abuse, outright torture, or perilous escape plans—Strathairn is equally credible as a young soldier in retreat from the front, a diplomat/spy in his late 20s who is sworn to protect his homeland unto death, or as a mature, nearly broken man. “Governments have no souls. … Individuals have souls.” This mantra becomes a lifelong one for Karski.

Whether it’s the sting of his beating by Nazi guards or the impact of his fall as he jumps from his hospital window to escape, Strathairn’s visceral performance is immediate. He moves seamlessly from one accent to another, beginning with Karski’s Polish-accented English and continuing with those of politicians, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Britain’s prime minister Anthony Eden, who obfuscate and obstruct aid to refugees from the Nazi regime. Among the characters he plays is expatriate Szmul Zygielbojm, Karski’s London-based Jewish alter ego and conscience.

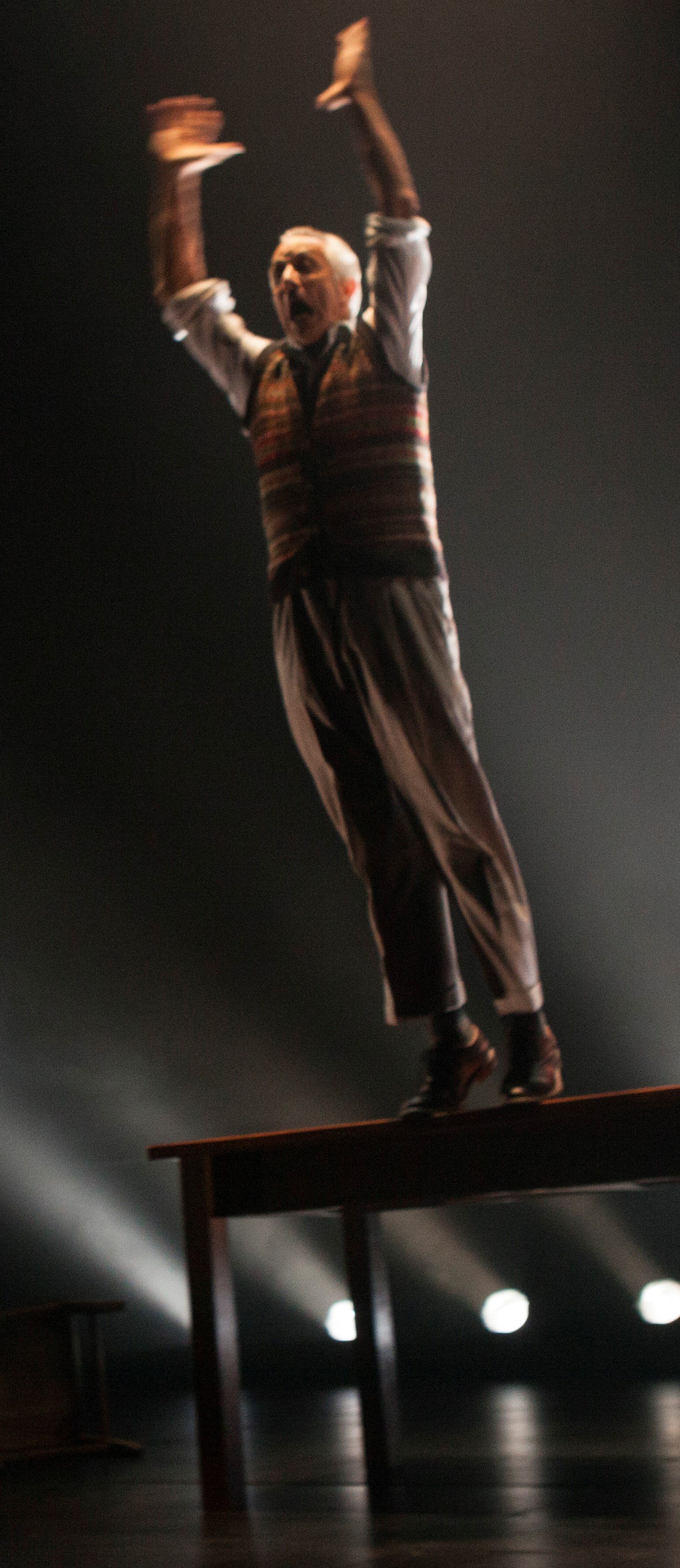

Strathairn’s Karski is about to jump to his freedom. Photograph by Hollis King.

Director Goldman, with masterly use of limited stage space, has created plausible venues for Karski’s multiple diplomatic meetings and clandestine rendezvous. Karski uses the spaces for his gut-wrenching confrontation with his own demons and those of others, including the tortured Zygielbojm. Straithairn’s movements, as directed by movement director Emma Jaster, are beyond purposeful and appropriate. They are fluid, elastic, and at times, gymnastic and expressionist.

Strathairn’s performance is enhanced by Roc Lee’s superb original composition and sound design. When young Karski retreats from the advancing Germans, the sounds of falling bombs and artillery fire are chillingly real. Zach Blaine’s lighting foreshadows impending disaster: at the smoke-filled front, where the Germans decimate the Polish army; near the border with Slovakia, where, following Karski’s aborted crossing, a Nazi soldier shines a beam in his face; and at other times when Karski’s life is at risk. Misha Kachman’s deceptively simple set, wooden table, and chairs, serves multiple functions as university classroom, hospital bed, desk, jail cell, and interrogation station.

It is unclear from the play whether Karski, having failed to awaken world leaders’ mercy on behalf of a condemned remnant of Jews, ever makes peace with himself. Not even a marriage to acclaimed Polish Jewish dancer Pola Nirenska, whose relatives perished at the hands of the Nazis, fully heals him. It seems implicit that teaching at Georgetown University from 1952 to 1995 brought him some level of closure and comfort. Nevertheless, Remember Me lends credence to those who view history as the best drama.

Remember This: The Lesson of Jan Karski runs at Theatre for a New Audience, Polonsky Shakespeare Center (262 Ashland Place, Brooklyn) through Oct. 9. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and Sunday. For tickets or more information, call (212) 229-2819 or visit tfana.org.