Leaving no explorer-themed cliché unturned, Ernest Shackleton Loves Me boldly goes where many, many musicals have gone before, weaving a story of ersatz empowerment out of artistic crisis. The show, which encumbers a pair of insanely talented performers with thankless roles at the center of a human cartoon, patronizes and demeans its audience in its eagerness to be idiosyncratic.

Marry Harry

Marry Harry revives a genre not much seen in these parts lately, the charm musical. The work of Jennifer Robbins (book), Dan Martin (music), and Michael Biello (lyrics), the show is small and hasn’t much on its mind, just the urge to put a few likable characters through a simple story and send its audience out with a collective feeling of “Aww.” Thanks to an attractive production on the intimate York Theatre stage and an overqualified cast, it gets its “Aww,” though it also earns a couple of orders of “You can’t be serious.”

Baghdaddy

A night at the newest production of Baghdaddy might begin with a cup of coffee, a doughnut, and a name tag. From the start, the audience is thrown right into the midst of Marshall Pailet and A.D. Penedo’s punchy political musical. Actors sit in the audience, and audience members sit on the stage as the show begins with a support group for the CIA operatives and others who played a role in starting the war in Iraq.

The Lightning Thief

Poor, put-upon Percy Jackson. All he wants is to stay at the same school for more than a year. And have more than one friend. And not get in trouble all the time. And not have attention deficit disorder. Or such a rude, acrid stepdad. And if only that minotaur hadn’t killed his mom…

Peer Gynt and the Norwegian Hapa Band

The Ma-Yi Theater Company’s Peer Gynt and the Norwegian Hapa Band offers a sonic interpretation of Henrik Ibsen’s saga Peer Gynt. Ibsen wrote Peer Gynt in 1867 as a dramatic poem, and it was staged a decade later with music by Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg that has become famous. The play touches upon Norwegian mythology and folk tales, and it captures the hard and difficult times of mid-19th-century life in Scandinavia.

Made in China

Made in China is a decidedly adult musical from Wakka Wakka, a New York–based theater company that prides itself on challenging “the boundaries of the imagination” with “bold, unique, and unpredictable” entertainments. This visually engaging production is performed by a host of black-veiled puppeteers manipulating intricately crafted bunraku-style puppets designed by Kirjan Waage. The script, by Waage and Gwendolyn Warnock (“with help from the Made in China Ensemble”), pushes the boundaries of puppet earthiness with a vengeance—it features puppet nudity, a puppet performing ordinarily private bodily functions, puppet copulation (both human and canine), and a puppet-dragon that has a mind-blowing digestive system.

I Like It Like That

One way in which musical theater rises above and beyond straight drama in its delivery is that song is like a shortcut, overtaking the spoken word, when reaching out and touching its audience. Fans will be pleased to know that I Like It Like That is a new musical that really delivers.

Life Is for Living

He was a jack of all trades artistic and master of them all. Trendsetter and admired cultural icon, Noel Coward was a British actor, playwright, dancer, composer and lyricist of songs, musicals and operettas, screenwriter and director, painter, novelist, and diarist, whose style, rapier wit, and intellect dominated the worlds of British theater and entertainment throughout the 1930’s, ’40s, and ’50s. Coward is the larger-than-life subject of Simon Green and David Shrubsole’s intimate evening Life Is for Living: Conversations with Coward at 59E59 Theaters. The presentation, the newest in a series of this British team’s collaborations devoted to Coward, uses Coward’s songs with excerpts from his diaries, verse, and letters, to offer us a glimpse into the breadth, artistry, life, and wit of the Master.

Othello: The Remix

As one of Shakespeare’s most famed tragedies, Othello has seen quite a number of adaptations over the years. The artistic duo Q Brothers take their stab at adapting this timeless play with Othello: The Remix, which discards Shakespeare’s original iambic pentameter in favor of modern rhyme set to rap music. In the spirit of Hamilton and other sung-through and hip-hop-infused musicals, Othello: The Remix is 80 minutes of fast-paced lyricism—spun live by cast member DJ Supernova and with hardly a breath in between. While there are a few questionable production choices, the massive amount of creative energy and impressive talent on display in Othello: The Remix make it hard to resist.

Sweet Charity

The musical Sweet Charity has good bloodlines—book by Neil Simon, music by Cy Coleman, lyrics by Dorothy Fields, original direction and choreography by Bob Fosse—yet the 1966 show has never occupied the top tier of musicals, such as My Fair Lady, South Pacific, Fiddler on the Roof or Gypsy. It has hardly languished in obscurity—there was a decent Broadway revival in 2005—but the New Group production directed by Leigh Silverman is such a persuasive delight that you may come away thinking it is top-tier after all. The production benefits from a terrific performance by Sutton Foster, a two-time Tony winner (and star of TV Land channel’s popular series Younger) in the title role. Foster is better known for big-budget Broadway shows such as Thoroughly Modern Millie and Anything Goes, but it’s a thrill to see her work magic in close quarters.

My Name Is Gideon: I’m Probably Going to Die, Eventually

Every now and then a theatrical experience comes around that breaks the mold. It’s no simple task to categorize Gideon Irving’s performance piece running at the Rattlestick Playwrights Theater. Part musical, part stand-up comedy, (very small) part magic act, and part intriguing night in a complete stranger’s living room, My Name Is Gideon: I’m Probably Going to Die, Eventually is far from a one-trick pony. On the contrary, the hour-and-45-minute show is constantly surprising audience members with laughs, gasps, songs and even snacks!

tick, tick...BOOM!

For the late Rent composer Jonathan Larson, the “tick, tick, boom” in his head were the sounds signaling the passage of time as he matured and yet struggled to achieve success in the theater. Although Tick, Tick… BOOM! was originally written as a highly autobiographical solo piece, it was reworked after Larson’s death and the success of Rent to include two more characters, a girlfriend and a roommate. Fans of his 1996 hit rock musical are likely to thoroughly enjoy the Keen Company production of Tick, Tick… BOOM!

Miranda Rights—And Wrongs

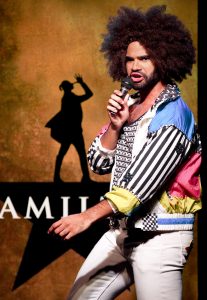

Perhaps it was inevitable that Gerard Alessandrini, the creator of many seasons of Forbidden Broadway, would be lured back by the possibilities of the phenomenon of Hamilton. Having put the long-running satirical revue on hiatus in 2014 (after Forbidden Broadway Comes Out Swinging), Alessandrini has devised a terrific new show, Spamilton, at the Triad. Structured around Lin-Manuel Miranda’s runaway hit, the show features a stronger through-line than Alessandrini usually fashions to encompass the revue elements. For lovers of musical theater, Forbidden Broadway, and Hamilton, Spamilton provides a raucous goulash of mostly on-target barbs, yet it is also in the Forbidden Broadway mold, with “appearances” by stars such as Bernadette Peters, J. Lo, Beyoncé, and, inevitably, Liza Minnelli. Most important, fans can rejoice that Alessandrini is back at the top of his game. And the targets are not just Hamilton the musical, but the art form itself, the actors in Hamilton, and anything currently on Broadway.

The revue, written and directed by Alessandrini, takes the form of a fantasia. Inspired by the Kennedys and their love of the musical, Camelot, which Jackie said she played each night at bedtime, he imagines the Obamas turning in, with the President (Chris Anthony Giles) putting on a vinyl of Hamilton. Then Alessandrini lets loose. Part biography, part parody, the show details Miranda’s upbringing, his love of musicals, and his determination to build a better Broadway musical, in a clever rap that upends the expectation of traditionalism from him:

This blue collar shining beacon/Puerto Rican/Got a lot farther/By being a lot smarter/By stretching rhymes harder/By being a trend-starter.

Lurking beneath the flattery of “trend-starter,” though, is Alessandrini’s deep skepticism about rap as a medium for shows. Later in the revue, to the tune of “Children Will Listen,” from Into the Woods, he writes:

"Careful the rap you play/No one will listen/Careful how dense the phrase/ People will leave/Or heave."

“Children like rap today/But children don’t listen/Parents may lavish praise/But they could deceive/So take it from me/Careful the rap you say/ Incessantly/No one will listen."

Yet the canny creator also realizes that Miranda didn’t come out of nowhere. He has been influenced by Sondheim, whose genius has spawned inferior work from countless lesser talents. To the music of “Another Hundred People,” from Company, Sondheim gets his share of blame:

“Another hundred syllables came out of my mouth/And fell onto the ground/While another hundred syllables are gonna go south/And are sticking around/As another hundred syllables repeat the refrain/And are waiting for us/In the second quatrain/And I’m starting to cuss/Ev’ry word I say.”

“It’s a lyric by Sondheim/All you can eat word buffet/A lyric by Sondheim/ Too hard to sing, or to play/And ev’ry day/Some say, ‘No way…’”

Nora Schell, a powerhouse singer, delivers the Sondheim parody with panache, and she plays Michelle Obama and most of the other women’s roles. Gina Kreiezmar appears as a guest diva to play a beggar woman trying to cadge tickets to Hamilton, to the tune of the Beggar Woman’s “No Place Like London” in Sweeney Todd, and as Liza Minnelli she sings, to the tune of “Down With Love,” “Down With Rap”: “Down with rap and all of the hip-hop trends/Down with rap and all of the rhymes it bends.”

Aficionados will have fun identifying the melodies and references, which include Camelot, of course, but also The Unsinkable Molly Brown, The Music Man, Sweeney Todd, Into the Woods, and non-theater music such as the theme from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air. And, thanks to Miranda’s good nature, Alessandrini has permission to use music from Hamilton itself, which he does effectively—skewering Barbra Streisand in all her narcissism and her Revolutionary garb at the Tony Awards, singing, to the music of Miranda’s big show-stopper, “I wanna be in the film when it happens, the film when it happens…”

Occasionally, Alessandrini’s swift segues may leave one confused, particularly at the appearance of an old man who missed something because he went to the bathroom. But Spamilton thrives on the energy of its cast of talented unknowns, who include Nicholas Edwards as a prancing Daveed Diggs in a volcanic wig (Diggs the actor is satirized in the number “Fresh Prince of Big Hair”) and Juwan Crawley, whose appearance in Dustin Cross’s costumes (as the genie in Aladdin and as a rather famous orphan) are the juiciest sight gags of the evening.

Whether or not you view Spamilton as a stopgap till you can score tickets to Hamilton, or as a exemplar of sharp-witted parody, Alessandrini’s show is chock-full of pleasures.

Spamilton plays through Dec. 31 at The Triad Theater. Tickets at $69 are selling quickly but are available for the popular show beginning Oct. 5. There is a two-drink minimum and cabaret seating. Performance times vary; for information and tickets, visit triadnyc.com.

Looking for God and Love

Serious pianists love to study the great composers in order to explore and channel the music they are to perform. Hershey Felder, the writer and star of the solo show Maestro, is a serious pianist and composer in his own right. He is also a gifted and highly successful singer, director, and producer. His one-man show is the natural rumination of one serious musician about another.

Maestro is the story of the larger-than-life phenomenon that was Leonard Bernstein: conductor of the celebrated New York Philharmonic and orchestras worldwide; the second most performed classical composer in the United States, who also wrote the scores for the hit West Side Story and other Broadway shows; the creator of 53 Young People’s Concerts and proselytizer on behalf of the classical music tradition to the millions he reached on TV and in lectures all over the world. In this and other plays, Felder has created a piece of biographical theater. His one-man plays about Gershwin, Chopin, Beethoven, Liszt, Irving Berlin, and now Bernstein, use story, song, and music to probe the lives of great musicians and deepen our understanding of music itself.

Bernstein’s overarching passion was to compose. In Lenny’s voice, Felder explains what lies behind the works he composes: “and in every one of these pieces, I am busy looking for God. And for love. Because as composers, that’s what we’re always doing.” This desire, the desire to compose and all it encompasses, is the spine of Felder’s play. Will Bernstein find God? Will he find love? Will he write the great works he so badly wants to write?

Felder takes on Lenny, the controversies about his life and his music, and looks for the truth behind the noise of his fame. He shows us a man whose betrayal of his marriage and loss of his wife to cancer upended his life. And he shows us a man who, for all of his achievements as a composer, was never embraced by the classical composing establishment, which rigidly favored atonalism. Bernstein not only believed that tonality and melody were at the heart of all great classical music, he wrote successful musicals; brought classical impulses into his popular music; brought popular idioms into his serious classical compositions; and was just too populist in every way to win the seal of approval of that elite club whose tenets he rejected. He paid a heavy price.

Beautifully directed by Joel Zwick, the work uses projection and lighting (Christopher Ashe) as well as audio (Eric Carstensen) in striking, even brilliant ways. Does Felder do justice to Bernstein? Do we know the man more deeply after the play than we did before? These are questions that theatergoers will answer for themselves. But in bringing us a character whose passion and achievements were in music, Felder’s own musicianship, his teaching moments riffing on music that occur throughout the play, and his prowess at the keyboard, bring us more deeply into the soul of Bernstein than this genre might have otherwise permitted.

A solo show is a special feat for any actor. Maestro runs one hour and 45 minutes and includes challenging work at the keyboard, some of it while also singing or speaking. At the same time, is it mean-spirited to say there is a bit too much West Side Story and that, if the final song were cut, the play would end on the more tragic note intended by Felder, without sentimentality? Interestingly, as a baritone, Felder sings in a soft and lilting popular style and also in a steelier, more trained classical style, sometimes combining both, just as Bernstein was forever migrating from one style to the next in unexpected ways. Vocally this usually works—but not always.

Did Bernstein find God and love in his composing and in his life? In the most powerful moment at the end of the play—better experienced than described here—Bernstein combatively turns and asks questions of the audience. Then he recites a poem Bernstein wrote in which he sums up how he views his life in the face of his approaching death. Did Bernstein find God and love in his composing? No, Felder says, not in Bernstein’s eyes. And yes, Felder says, in the eyes and hearts of all of us who listen to his story and, even more important, to the maverick genius and passionate heart of the music that beats beneath it.

Maestro runs through Oct. 23 at 59E59 Theaters (59 E. 59th St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tues.–Thurs. and at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Saturday and 3 p.m. Sunday. (Additional performances are at 2 p.m. Sept. 29 and Oct. 13. There are no performances on Sept. 24 or Oct. 11 or at 7 p.m. Oct. 2.) Tickets are $25–$70. For more information, call Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200 or visit www.59e59.org.

Liberty for All

Liberty: A Monumental New Musical captures an America not unlike the one we see today: a place where people want to come, but also where many struggle to find work and build a simple but stable life. The story begins when Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi, a French artist, lovingly completes his statue and sends her to the United States (it's a gift from France to commemorate a century of independence), as if she were his own child. Liberty (played by teenage actress Abigail Shapiro) comes looking for a pedestal on which she can stand to spread her message of hope and freedom.

However, when she arrives at Ellis Island, she is given the same treatment as every other immigrant. She is poked and prodded, and given the twice-over; only to be rejected—after all, what is her purpose here anyway? Hope? That’s not enough. Commissioner Francis A. Walker, who was responsible for the census in the mid-1800s (played with a debonair charm by Brandon Andrus), schedules her to return to France on the next boat. Liberty perseveres. After all, hope is not only for the immigrant, but for everyone seeking freedom and a better life.

The wonderful cast brings life to a variety of characters: an Italian immigrant (Nick Devito), an Irish foreman (Mark Aldrich, who also plays news mogul Joseph Pulitzer), a Russian knish seller (Tina Stafford, who moves gracefully between the Russian Olga, and a wealthy American heiress named Regina Schuyler), a former slave (C. Mingo Lingo), and a native American Indian (Ryan Duncan).

Liberty is a love song to New York—a city that embraces everyone, or at least tries to—but it’s also a history lesson. There’s a great deal of information about Emma Lazarus, played with tight-lipped determination by Emma Rosenthal, who is the most well-drawn character in the play, and the most interesting. She teaches English to Giovanni, an Italian immigrant who seems to hang around the port (is he being deported, or just a loafer?). His improved English increases his betting options: “Ten to one!” he says triumphantly and skitters off. Emma looks after him with a wry smile, clearly amused. This intrigue, however, is forbidden: Emma is from an affluent Jewish family that has been in America for four generations. Hanging around the port and new immigrants is not what a society girl is supposed to do, even if she is a poet, and Regina Schuyler, a wealthy woman who puts her money where it will give her the highest profile, makes sure Emma knows she’s being watched.

With book and lyrics by Dana Leslie Goldstein, there are some laughs along the way. Particularly funny are “The Charity Tango” sung by Liberty, Commissioner Walker and Schuyler, and “We Had It Worse” in which the Russian immigrant Olga and the Irish immigrant Patrick McKay compete to see who had it worse when they first arrived in America. However, as they crescendo in their comparisons, they also discover they agree on something when they sing: “Kids have no idea what hard work is” (…) “Soft” (…) “like a boiled cabbage,” and do a double-take in each other’s direction; they finish the song with a broad smile.

The production is fun, and kid-friendly, but very uneven. While the libretto is outstanding, the music by Jon Goldstein sounds canned; all the tracks seem to have been created on a synthesizer. The stage also feels small, not only because it is small, but because Evan Pappas's staging lacks dynamics and, at times, deflates the production. Some choreographed movement would have given the actors some breadth and depth and the production real musical-theater flair. Nonetheless, the cast clearly has their musical theater chops, and is led to a hopeful finale by Lady Liberty, who proves that perseverance pays off—a message we know is often true.

Liberty: A Monumental New Musical plays an open run at 42 West, 514 West 42nd St., between 10th and 11th avenues. Performances are Sundays at 2 and 5 p.m.; Mondays and Wednesdays at 3 and 7 p.m.; and Thursdays at noon and 3 p.m. Tickets are $72/$36 (premium/child premium); $63 (adult); $27 (children 4-12) and may be purchased by visiting LibertyTheMusical.com.

A Heartsong for Hades

Anaïs Mitchell’s Hadestown, a concept album turned folk opera, adapts the myth of Orpheus by infusing it with American folk and New Orleans jazz music. Now playing at New York Theatre Workshop, Hadestown follows Orpheus (Damon Daunno) to hell and back again in pursuit of his young lover, Eurydice (Nabiyah Be), who has been lured there by the lord of the underworld, Hades (Patrick Page). Being a “folk opera,” the production is almost entirely sung-through, and Rachel Chavkin’s direction carries one song fluidly into the next. Like its classical source, Hadestown is alternatively gorgeous and dark, and the heartfelt commitment of the cast and musical ensemble brings the myth’s paradoxically sad beauty into full bloom.

As an energetic balance of hope and sadness, Hadestown finds light in the darkness and vice versa. The production’s casting reflects this balance: the naiveté of Be’s Eurydice and Daunno’s Orpheus contrasts starkly with the underworldly knowingness of Amber Gray’s Persephone and Chris Sullivan’s Hermes. Sullivan’s portrayal of his character is particularly complicated, as an enlisted messenger for the underworld with a soft heart for the young lovers. The Fates (played by Jessie Shelton, Shaina Taub, and Lulu Fall) are similarly uncommitted in their alliances, singing at times of great love and at others of shattering despair. As the brooding, unrelenting Hades, Page’s reverberating bass vocals figuratively open the doors of hell itself. In voice and movement, this hugely talented ensemble strikes near-perfect harmony in Act I. Act II contains major strengths, including some of the show’s most tear-jerking moments, but overall it lacks the simpatico energy of Act I.

Based on Mitchell’s celebrated folk album, music is the absolute center of Hadestown. Indeed, at times this music-forward production feels more like a highly-produced concert than a play—which works well with such a polished songbook. Michael Chorney and Todd Sickafoose’s co-arrangements and Liam Robinson’s musical direction sonically transform the space into a concert-in-the-round, immersing audiences with powerful voices and instrumentals.

Chavkin puts the space, reconfigured to stadium seating, to great use with entrances and exits from all angles and levels. Visually, Bradley King’s lighting synergizes with the music, especially in Act I’s penultimate “Wait for Me.” In this number, the Fates swing hanging wire lamps to and fro, visually embodying the show’s undulating emotional landscape between hope and uncertainty.

Adapting ancient Greek myths is nothing new for off-Broadway directors, but Mitchell and Chavkin’s Hadestown feels particularly fresh right now. In the “Wedding Song” Eurydice asks her new lover Orpheus how their young, penniless relationship will ever survive with “times being what they are—dark and getting darker all the time.” Eurydice’s ambiguity resonates in a time when the American middle class is dwindling and senseless acts of violence continue to erupt here and abroad. Later in Act I, Hades delivers a timely diatribe in the song “Why We Build the Wall,” echoing the latent xenophobia drummed up by the current election campaign’s fear-based politicking.

At the same time, amid this darkness, the pure love between Eurydice and Orpheus shines through—even Hades and Persephone's fraught relationship contains a hidden softness. Indeed, the sweet vulnerabilities embedded in the music and performances of Hadestown convey the very joys and hardships that make being human so painfully beautiful.

Hadestown runs through July 31 at New York Theatre Workshop (79 E. 4th Street between Bowery and 2nd Avenue.) No late seating. Tickets are available here or by calling 212-460-5475.

Number One or Number Two?

Comedy is a tricky commodity. Many a writer, comedian, and movie has gone down in flames, and it would be too simple to say that it’s all in the writing. Yet, even the best comedic writing in the wrong hands can feel flat and lifeless. Satirical, musical comedy is even more challenging. Some of the best theater has been created by a team, adept at pulling and pushing each other to new heights. Here I Sit, Broken Hearted ... A Bathroom Odyssey is written, directed, and stars Seth Panitch with original music by R. Johnson Hall. It chronicles the world of bathroom graffiti and also stars Ian Anderson, Matt Lewis, and Chip Persons.

The set design, by Mike Morin, is a men’s bathroom with four stalls scribbled with graffiti. The back wall above the stalls is used for projection of corresponding graffiti and photos; given the set design, it is difficult to read the visuals displayed and it quickly becomes annoying. The speakers for the music are keenly hidden in the trash receptacles on either side of the stage.

Coughing and shuffling can be heard behind the stall doors and they open to reveal the actors sitting on the commodes. Spoofing “Taking a Chance on Love,” they begin to sing.

Here I go again,

I hear those trumpets blow again.

Me on my throne again...

Taking a chance on love!

Sadly, the comedy of Here I Sit, Broken Hearted never rises above these lyrics; it misses the mark on practically every level. The saving grace, beyond the short 60-minute length, is the pure joie de vivre of the cast, specifically Anderson and Lewis. If the actors suspect that the material isn’t funny, current, or satirical, they never let on. Purely for trying to make it work they deserve kudos. A cameo appearance by an unnamed young woman is quite cute. Thinking she’s entered the women’s room, she walks in to find four white guys rapping. Incredulous, she asks “Were you guys ... you didn’t happen to be—rapping, did you?”

The fault in this piece lays squarely on Panitch. When one is so heavily entrenched in the creative process, it can be difficult to step far enough away from the material to discern what’s really good and what should be dumped. The monkey mind keeps insisting, ‘This is really good.’ This time the monkey lied.

With "South Park" and The Book of Mormon, not to mention countless movies, bathroom humor, full of innuendo and fart jokes, has been done, and Here I Sit, Broken Hearted feels dated. It takes a deft hand and slightly twisted mind to write new bathroom material. The song choices sound as if they are meant for an older audience, as well as the lyrics. Imagine the Catskills circa 1970. Second, it’s unusual to find a public bathroom like this any longer except at the beach or maybe a highway rest stop, so the references are difficult to pull off in 2016 Manhattan. A giant blow-up condom bit, immediately followed by a scene with two giant blow-up penises, is not even sophomoric enough to relish a laugh.

Given the sexual exploits of politicians and bathrooms, Panitch misses opportunity after opportunity, instead choosing to dress two of the actors to look like Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton who have little, if anything, to do with a public restroom. Gilded, maybe, but a public restroom, hardly. Public restrooms are notorious for sex, yet there is little that is sexy about Here I Sit, Broken Hearted.

While the four actors get on and off the toilets they continually wear some form of underwear. There are countless ways to be coy and funny while teasing some nudity, a la the full monty, with sleight of hand or lighting, and it would seem appropriate for a bathroom musical. Instead, they continue to pull up underwear on top of underwear, stopping short of what could have been quite fun.

The icing on this pile is when Panitch recounts a visit to the Western Wall in Jerusalem when he turned 13, seeing prayers stuffed into the crevices between the ancient stones. “So, when I entered that fateful bathroom stall that day, and saw once again that famous refrain on the wall, I was strangely reminded of the Western Wall.” Attempting to correlate one of the most sacred sites on the planet, holding the prayers of the faithful, to bathroom graffiti is beyond a stretch of the imagination and borders on the profane.

Here I Sit, Broken Hearted… A Bathroom Odyssey runs until July 9 at the Beckett Theatre at Theatre Row (410 W. 42nd St. at Ninth Avenue). Performances are Wednesday through Saturday at 8 p.m. and Sunday at 3 p.m. Tickets are $19.25. To purchase them, call 212-239-6200 or visit Telecharge.com.

à la

Comedy and Cabaret Cocktail

Audiences at the Broadway Comedy Club are in for some head-scratching and knee-slapping as the cast of On The Spot improvises and sings its way to creating a zany new musical performance every Monday night. The cast, made up of five singers, four improv actors and one pianist work together to create an entertaining, eclectic and somewhat perplexing hour and a half of comedy and cabaret.

Jesters of the Jazz Age

The Marx Brothers—four actual brothers, best known for their timely political commentary, sophisticated puns and physicalized comedy—left no stone unturned. They poked fun at everyone and everything: aristocrats, hobos, history, and especially relationships between men and women. I’ll Say She Is, now at the Connelly Theater, written by Will B. Johnstone, went to Broadway in 1924 and put the Marx Brothers on the map. Their rise was mercurial, and they made many movies that spread their popularity even wider.

But I’ll Say She Is, unlike their other stage shows, never became a film. It centers on a rich heiress named Beauty, played by the lovely Melody Jane, whose problem—“Society Woman Craves Excitement”—headlines the newspapers. The Marx Brothers, actors looking for work, are sent by their casting agent to woo her, and presumably get money from her. After all, her problem seems to be of great local concern. Fabulously rich, she lives with her also very wealthy aunt, Ruby, played by Kathy Biehl, who lends the role the right amount of stentorian authority. When the Brothers arrive at Ruby and Beauty’s door, the butler, played comically by C.L. Weatherstone, asks: “Gentlemen, did you come by appointment?” to which Chico responds, “No, we came by subway.”

The literal use of language is what made the Marx Brothers so brilliant. When Chico asks Harpo to cut the cards, he takes out an ax and chops them up. However, their comedy doesn’t completely rely on fast-paced antics. Instead, there are many quieter, more theatrical moments, as well as moments that showcase the array of talent the Marx Brothers had. Harpo was a gifted harpist, and Chico learned to play the piano with a special one-handed technique, and the actors successfully capture these talents.

When actors play famous personae, we want to see exactness, but what we really should be looking for is likeness. The four actors who play the Marx Brothers do a fantastic job of capturing the broader aspects of each of the brothers’ personas. And personas they were. Matt Roper captures Chico’s tight-lipped, one-sided grin, casts the sideways glances that made Chico seem both wary and earnest. Seth Shelden plays Harpo’s muteness with energy. Harpo was a pickpocket of sorts, and to recreate this theatrically takes a certain kind of magician’s ability. In one scene, Ruby suspects that he has stolen some cutlery, but she then backs off her claim. At the same time, several forks, spoons and knives fall out of Harpo’s sleeve. Shelden masters the great physical control needed to play Harpo’s mute but mischievous character.

Groucho was surprisingly successful in romance. The older women adored him for his quasi-romantic nature, and sharp humor. During a scene while courting Ruby, she calls, “Ah! My dear! At last I’ve found you.”

Groucho: “Yes, my darling, here I am.”

Ruby: “I was referring to my niece.”

Groucho: “Well, I’ll have you on your niece in no time.”

However, his exaggerated black eyebrows, painted thickly above his own, the long waistcoat, and cigar dangling from the side of his mouth make him also the most comical-looking. Noah Diamond does a wonderful job of getting Groucho’s famous walk just right with the back bent forward, and knees in a deep plié that often made Groucho look like he was gliding across the room.

And last but not least, Matt Walters plays Zeppo with all the leading-man charm reminiscent of those classic film stars Cary Grant and Clark Gable. Beauty falls in love with him at the end of the play and realizes that “there is no greater thrill than the thrill of love.”

Diamond lovingly restored the lost script by working with Johnstone’s rehearsal notes to adapt the play to the Connelly Theater, a historic venue dating back to the mid-1800s. Director Amanda Sisk, choreographer Shea Sullivan, and musical director Sabrina Chap do a marvelous job of capturing the voluptuousness of a Broadway revue during the age of vaudeville. The play, produced by Trav S.D., includes an array of 10 chorus dancers who are a triple threat: they dance, sing, and act. And of course, they all tap-dance. In their sparkly art deco dresses they bring an additional vibrancy to the stage that makes the play all the more fun in its reminiscence of a vaudeville spectacle.

I’ll Say She Is runs through July 3 at the Connelly Theater (220 E. 4th St., between Avenues A and B). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Thursdays through Saturdays and at 7 p.m. on Sunday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Sundays. Tickets are $35 ($25 for students and seniors), available at 212-352-3101 or www.illsaysheis.com.

Fine, Blame It on the Woman

August Darnell and Vivien Goldman’s new musical Cherchez La Femme, based on Darnell's 1976 hit song of the same name, opens with “Let’s Dance.” It is rhythmic and hot, and the beat permeates the house. The music is recorded, but the singing is live and jumpin’—the party is in full swing. The scene is 1980s New York, just as Caufy Keeps, played by Isaac Gay, is about to launch a much-anticipated tour with his backup singers, the Lemon Drops. The story is loosely based on Kid Creole and the Coconuts and their extraordinary influence on disco—fusing it with Caribbean, Latin, and a whole lot of Cab Calloway.

The book by Darnell and Goldman follows Caufy from New York, where his girlfriend has left him, as he heads for Haiti. Heartbroken, Caufy skips the tour. Instead he takes his sidekick Stingy Brim (CB Murray), often referred to as “brother,” along with his personal assistant to find her in Haiti.

The plot-heavy story includes a young woman who has been stalking Caufy in New York and announces that she is his daughter from a tryst in Oslo 20 years earlier. The Lemon Drops, furious with his decision, head off on their own to become the toast of Paris. The many threads of the story require a suspension of disbelief—all the events appear to happen within days. Scenes in Haiti and Paris could just have easily taken place in a variety of clubs and heavily ethnic communities in New York.

Other aspects are also less than credible. A scene at Customs in Haiti is superfluous and made little sense in that Caufy’s illegitimate daughter shows up at the same time and is able to sway the argumentative Customs agents. With “Baby Doc” Duvalier in power, he has taken issue with Reagan and the U.S.—the Customs agents are more than happy to take a heavy hand with Americans. Act II opens with an odd cheerleader number that seems to have nothing to do with the story. The mother of Caufy’s daughter has an accent that is anything but Scandinavian, not to mention that, for some reason, she is also in Haiti.

The music is where the juice is, and credit (then, as now) goes to Darnell and Stony Browder Jr. Their commitment to the original style they created for Kid Creole, as well as the additional numbers written, completes the show. Add ’80s-inspired choreography by Kyndra “Blinkie” Reevey, and the energy is palpable. Showcasing the talented Kristina Hanford, the reprise of Cherchez La Femme with the full company brings down the house.

Cherchez La Femme belongs to Gay and Murray. As Caufy Keeps, Gay has the sex appeal, certitude, and chops to carry a musical. Stingy Brim, played by Murray, has the best lines of the show. Yet he seems to be challenged by the 2½-hour run time and too many story lines; hence, his delivery is rushed.

Angie Kristic is the director of Cherchez La Femme and, while it’s evident she brought a lot to the production, some editing of the extraneous stories is needed, along with smoother transitions between scenes and more tech rehearsals. The sound, more than anything, is a problem. There are too few speakers and they are poorly placed, with a heavy bass track producing unbalanced harmonies. For as much work as was put into creating and staging this production, the sound and the vocals deserve better.

Costuming (Adriana Kaegi) is pure ’80s, but a bolder color palette would work better, especially for the Lemon Drops. The baggy, zoot suit style of the period is correct; however, Stingy is in need of a good tailor. The choice of using necklaces as bribes for the Lemon Drops was a mistake given the lavalieres each is wearing, as they were difficult and too noisy to put on. Set design (Aaron Mavinga) is bare-bones and a tad too "high school musical"—spray paint, plastic martini glasses, and a cheesy room divider. The village set in Haiti is on point, but it is so far upstage that the distance from the audience has the actors scrambling to fill the space. The lighting (Joe Beahm) in Haiti is a little too soft, and the disco scenes missing the big ’80s flair; however, the fog is a cool touch in those scenes.

It’s rumored that the French meaning of Cherchez la femme—literally, “Look for the woman”—is sexist, meaning no matter what the problem may be a woman is often the cause. In this case, it’s more the lack of a stronger hand editing and some distance from the material, albeit male or female, to know what to keep and what to let go of. Cherchez La Femme has some really good bones—just a few too many to give it the long run it deserves.

Cherchez La Femme continues in The Ellen Stewart Theatre at La Mama (66 East 4th St., Manhattan), through June 12. Tickets are $35 for adults; $30 for students and seniors either online at www.lamama.org, by phone at 646-430-5374, or at the La MaMa box office: noon-6 p.m. daily.