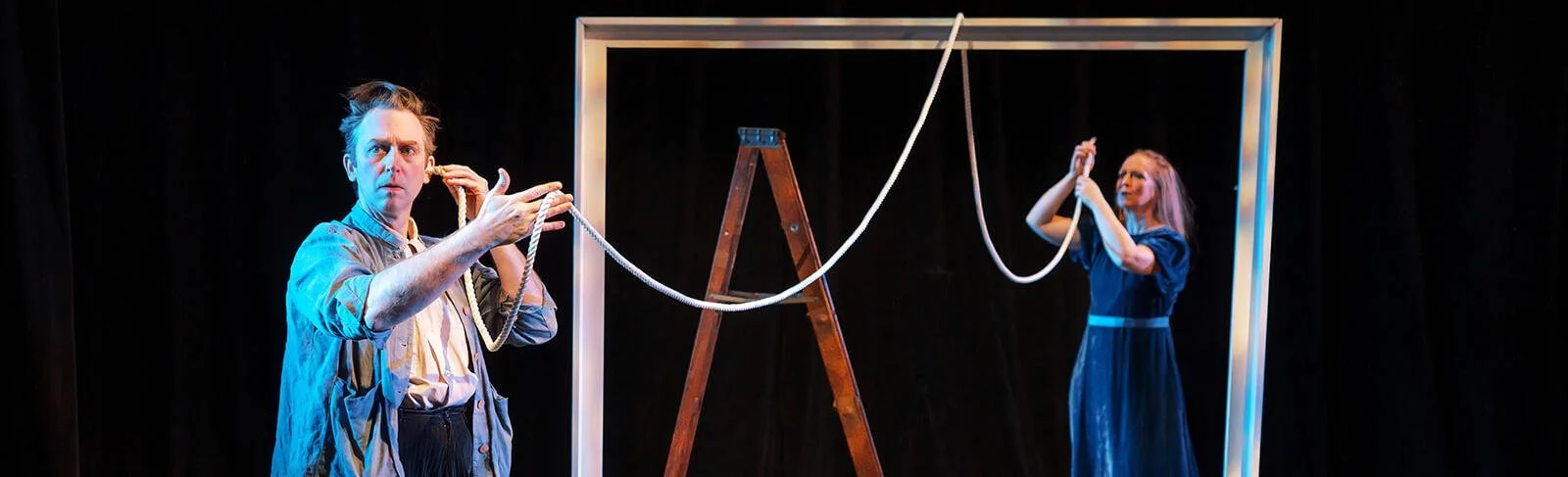

In 1881, Ibsen’s Ghosts was considered shocking for its critique of conventional morality and its unabashed treatment of venereal disease and religious hypocrisy, among other topics. While the specifics of the social issues that the characters grapple with are not pressing today—syphilis is a curable disease, a woman trying to leave an unhappy marriage is not unthinkable, nor is the idea that a person of high social rank might be a degenerate—moral hypocrisy, patriarchy, class resentment, and generational trauma are always ripe for the stage. The gripping, finely acted production of Ghosts now playing at Lincoln Center, directed by Jack O’Brien and adapted by Mark O’Rowe, threads this needle: it retains the historical setting (though with a framing device) and yet makes the moral debates feel like more than artifacts from another era.

Immersed in Ibsen

“Be careful whom you trust,” a maid whispers warningly into my ear as she swishes past me up a dark stairwell. This servant (played convincingly by Macy Idzakovich) is one of many peripheral characters haunting the halls of the historic Morris-Jumel Mansion in Journey Lab and Deaths Head Theatrical's The Alving Estate—an immersive staging of Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts. Indeed, ghosts are central to Ibsen’s body of work and this particular production, which explore the foibles of the living, as well as the hauntings of the familial past. Though The Alving Estate experience is not without its aesthetic shortcomings, it succeeds in convincing audiences that there are deep secrets hidden within the walls of this eerie mansion.

As my experience with Idzakovich as the maid demonstrates, the participatory nature of Journey Lab's aesthetic infuses Ibsen’s oeuvre with extra sex and intrigue. Journey Lab’s take on Ghosts, like many immersive works today, puts the audience at the center of the experience, giving participants the opportunity to choose where to go (and who to follow) within the mansion. This production choice comes at the expense of narrative cohesion, so if you’re looking for something more experiential than narrative, this is your type of production; on the other hand, if you’re interested in piecing together a storyline, you should read or familiarize yourself with Ibsen’s play before indulging in The Alving Estate.

Upon arriving to the mansion, you are given a job description and prepped for an interview for employment at the estate. After socializing over drinks with other “applicants” in the charming and dimly lit carriage house, audience members are selected at random to begin exploring the mansion. The Morris-Jumel Mansion is itself a star character in this production; its creaks, draughts, and creepy oil portraits all add unique charm and mystique to the experience. Unfortunately, there are some informational plaques visible in parts of the mansion, which distract from the time and place of the immersive experience.

While the site of this performance provides a delightful opportunity to explore an old gem of upper Manhattan, there are other aspects of this production that are less unique. Journey Lab takes a great deal of cues from British immersive theater pioneers Punchdrunk and their long running production Sleep No More, which has been running in Chelsea since 2011. The resemblances between this production and the Punchdrunk aesthetic may distract audience members familiar with the Sleep No More empire. Eerie music, intense moments of eye contact with the actors, and choreography reminiscent of contact improvisation are all pulled directly from the existing repertoire. Even some of the costumes and props—backless ball gowns, old photographs, costume jewelry—seem to be hand-me-downs from The Alving Estate’s immersive predecessor.

Though The Alving Estate is haunted by an existing aesthetic, it still manages to showcase the raw talent and latent creativity of Journey Lab, an immersive company to look out for in the future. Surely, Punchdrunk provides a worthy aesthetic role model for aspiring immersive theater makers, but I suspect that the talent at Journey Lab could—and should—move beyond this copycat approach to become innovators in this exciting contemporary form.

The Alving Estate runs Thursday through Saturday at 7 p.m. until Feb. 6 at the Morris-Jumel Mansion (65 Jumel Terrace) in Washington Heights. Tickets range from $20-$50 and can be purchased by calling or visiting http://journeylab.org/experiences/.

Middle-Class Morality on the Block

Compared with A Doll’s House and Hedda Gabler, Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts usually has gotten short shrift as a dramatic document about women’s rights, even though its protagonist, Mrs. Alving, is as modern and self-sufficient as any Ibsen heroine. Richard Eyre’s astonishing adaptation, which runs only 90 minutes without intermission at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, confirms that Ibsen’s 1882 play is as timely as ever. None of the three acts feels foreshortened—it’s a full meal. It is also a magnificent production.

Both Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw, who championed the Norwegian playwright’s work in England, kicked Victorian melodrama to the curb, as it were, and introduced politically and socially conscious realism to the stage. At BAM, Eyre makes one feel the full weight of the change.

With only five characters, Ghosts also displays Ibsen’s characteristically tight plotting. Lesley Manville’s Helene Alving has welcomed her son Oswald (Billy Howle) home to Norway after has lived abroad for years. His father has died, and a new orphanage named for him is to be dedicated by Pastor Manders, a family friend, and, it turns out, someone with whom Helene had been in love. Indeed, she had left her husband, Captain Alving, with the intention of taking up with Manders, then a divinity student. Though the spark between them might easily have been fanned into a flame, he persuaded her to return to her home, where she remained as Alving’s seemingly loyal wife, though she eventually sent Oswald away to boarding school. Two additional characters, old Jacob Engstrand, a coarse and brutal carpenter with the idea of opening a “home away from home” for sailors, and his daughter, Regina, who works at the orphanage and loathes her father, are on hand as well.

As Mrs. Alving, Manville, a veteran of gritty realism in many Mike Leigh films, shows a character with personal composure and limited patience for cant. When Will Keen’s straight-laced, judgmental Manders notices pamphlets about feminism and free love on her parlor table, he takes her to task, but she challenges him—has he read them? “One must rely on the views of others,” he says, a response that echoes today in arguments involving morality and the church.

An early contretemps over whether the new orphanage should be insured provides an example of Ibsen’s mordant humor—something that director Eyre doesn’t stint on, in spite of the playwright’s reputation for seriousness. Manders understands the importance of insuring the new building, but he’s afraid that taking out insurance will imply that God can’t be trusted to protect the structure. When Helene finally acquiesces to his foolish view, Manville unveils the character’s frustration in the way she opens a desk drawer and tosses her spectacles and a blotter in. And Keen brings out every bit of Manders’s cluelessness, yet draws sympathy for a man who adheres to his hidebound principles, whose so-called morality has exposed his venality. The ghosts of the title, says Helene to Manders, are “the things that come out of the past…not just the people that haunt us, but what we inherit from our parents: dead ideas, dead customs, dead morals. They hang around us and we can’t get away from them.”

The strong stream of anticlericalism that runs through Ghosts (along with mentions of incest, syphilis, and sexual freedom) made it as big a target for condemnation as A Doll's House, and even today one can feel the earth tremble as Oswald excoriates Manders and his views. Oswald, who has lived in Paris among bohemians, espouses free love and expresses his disdain of Norwegian “worthies” who come to Paris looking for the sexual indulgences that they disapprove of at home. (One feels at times that Ibsen, who lived abroad for more than 20 years and carried on with a much younger woman, is speaking through Oswald.)

Bourgeois morality is also represented by Charlene McKenna’s Regina. She is ready for middle-class morality, and is attracted to Oswald—and vice versa. She wants the orphanage job to support herself and stay away from her father, who’s a drinker and a laborer. Old Jacob, too, schemes for advancement, but he also suspects that society would rather keep him in his place, so he latches on to Manders as an ally. One of the open questions in Eyre’s production concerns whether Manders or Engstrand is responsible for a disaster that upsets everyone’s plans.

The production, from the Almeida Theatre in London, looks terrific. Peter Mumford supplies crucial lighting, at two points a saturated red, and Tim Hatley’s set points up the compartmentalized lives of the people involved. Most important, Manville’s last scene shows that Ibsen still has the power to deliver a kick to the gut.

Henrik Ibsen’s Ghosts runs through May 3 at BAM, Harvey theater. Evening performances are at 7:30 p.m. Tuesday through Saturday, and matinees are at 3 p.m. on Sunday. Tickets may be obtained by calling 718-636-4100 or at the BAM box office at 651 Fulton St. in Brooklyn.