Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot begins with a declaration of futility. Estragon, one of the play’s tramps, attempts to remove an intractable muddy boot and despairingly announces, “Nothing to be done.” This sense of existential desperation pervades the New Yiddish Rep production, performed in Yiddish with English supertitles. Director Ronit Muszkatblit’s version has to be one of the bleakest in recent memory. While the approach may not appeal to casual theatergoers, Beckett devotees will find much to savor.

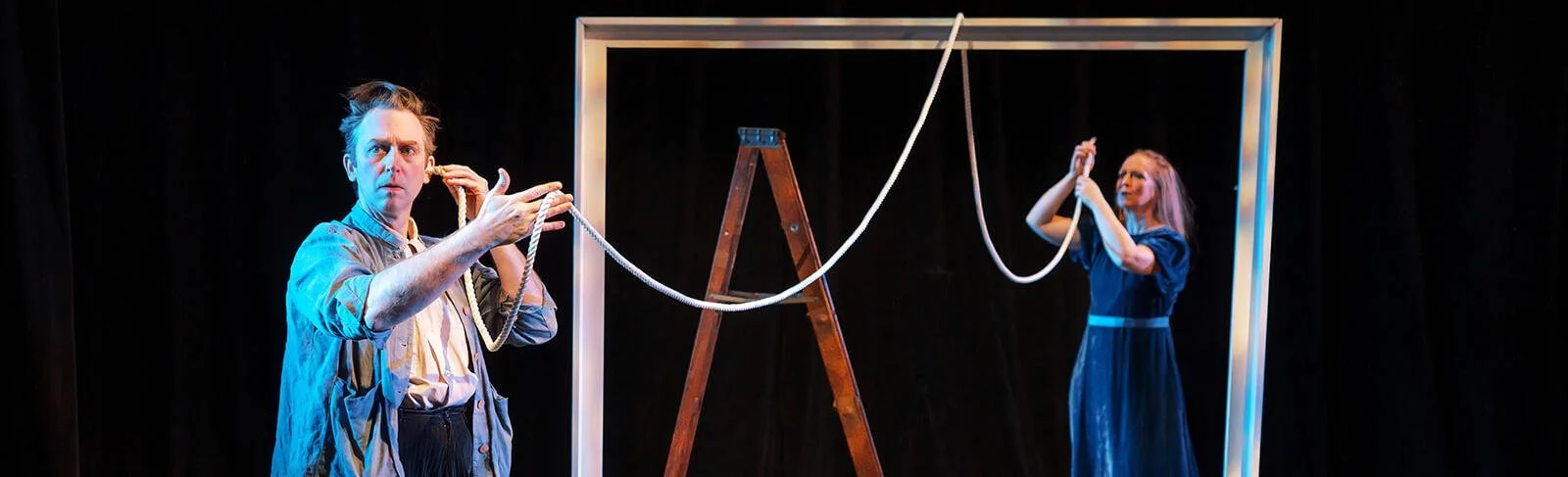

Richard Saudek plays Lucky in the Yiddish translation of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Top, from left: David Mandelbaum as Estragon and Eli Rosen as Vladimir.

Performing the play in Yiddish (Shane Baker has provided the translation) makes a great deal of sense because Godot can be viewed as a post-Holocaust response. Beckett was in the French Resistance, and he began writing the play just three years after the end of World War II. The monumental inconceivability of human cruelty, the Holocaust, and nuclear destruction pervade the text, and life, as reflected in the play, is senseless and completely expendable. As one of the characters says, people “give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.”

The production also draws on rich Yiddish performance traditions. Pre-show and intermission music includes Yiddish cabaret songs, and the pair of tramps, Vladimir and Estragon (Eli Rosen and David Mandelbaum), verbally spar with the cadence of early 20th-century Jewish comics and Borscht Belt comedians.

As the pair waits for the elusive Godot, they devise ways to pass the time. Yet unlike with other productions, Muszkatblit and her cast have not thoroughly mined the play for laughs. In the characterizations by Rosen and Mandelbaum, mustering even momentary amusement proves to be an impossible endeavor. They are simultaneously dependent upon and bored with each other. As Estragon says, “There are times when I wonder if it wouldn’t be better for us to part.” But like a couple in a codependent marriage, they bicker, hurl insults, and temporarily make up. This is their life, hour by hour, day by day, ad infinitum.

“Pre-show and intermission music includes Yiddish cabaret songs, and the pair of tramps verbally spar with the cadence of early 20th-century Jewish comics and Borscht Belt comedians.”

Their tedium is temporarily disrupted by the appearance of the arrogant landowner Pozzo (Gera Sandler) and his docile, bonded servant Lucky (Richard Saudek). Pozzo literally throws Estragon a bone, and Lucky provides a brief entertaining interlude. Even that becomes unbearable for the tramps. And when the boy (alternately played by Noam Sandler and Myron Tregubov) arrives at the end of each act to inform Estragon and Vladimir that Godot will not appear, the news is met with a collective shrug.

The effect generally works, but at times the leisurely pace and (for non-Yiddish speakers) alienating supertitles can be wearying for the audience, partly because of the central performances. Individually, Rosen and, in particular, Mandelbaum offer convincing and moving portrayals, but as a tragicomic duo, they do not always seem to be in sync. Their banter sometimes seems rather hesitant, and their physical comedy (such as lifting dead-weight bodies and trading bowler hats) can seem a bit under-rehearsed. They lack, for instance, the natural, easy timing that other clowns (Nathan Lane and Bill Irwin, to name just two) have brought to the parts. Granted, Rosen replaced another actor right before the show opened, so the pair still may be finding their rhythm.

Mandelbaum and Rosen as the tramps in Beckett’s existential tragicomedy. Photographs by Dina Raketa.

Sandler’s Pozzo is not a force of nature as one often sees, but his downplayed, almost offhand abusiveness is frightening in its ordinariness. As Lucky, Saudek is scarily good. Oppression and cruelty have sucked the life out of the character, but when ordered to dance and “think,” he is able to summon the remaining vestiges of physical and intellectual presence. Saudek’s slow-build then unstoppable first-act monologue is a coup de théâtre.

George Xenos’s tattered costumes and minimal scenery provide a dash of theatricality and creativeness: the play’s fundamental set piece, a tree—or is it, as the characters debate, a bush? Or maybe a shrub?—is the skeleton of a patio umbrella. Reza Behjat’s lighting is similarly effective, and the primary lighting effect, the moon rising, is engineered by the boy, who hangs a crumpled, illuminated globe from a visible wire.

Yiddish theater appears to be making a long-awaited New York comeback. (The acclaimed Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof is set to reopen Off-Broadway in a few weeks.) And while this Godot may not be the revelatory production theatergoers have been awaiting, it offers an intriguing new perspective on a familiar and well-worn play.

The New Yiddish Rep’s production of Waiting for Godot plays through Jan. 27 at the Theater at the 14th Street Y (344 East 14th St. at First Avenue). The play is performed in Yiddish with English supertitles. Evening performances are at 7:30 Monday through Sunday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Sunday. Tickets are $35 and may be purchased by calling (646) 395-4310 or by visiting www.newyiddishrep.org.