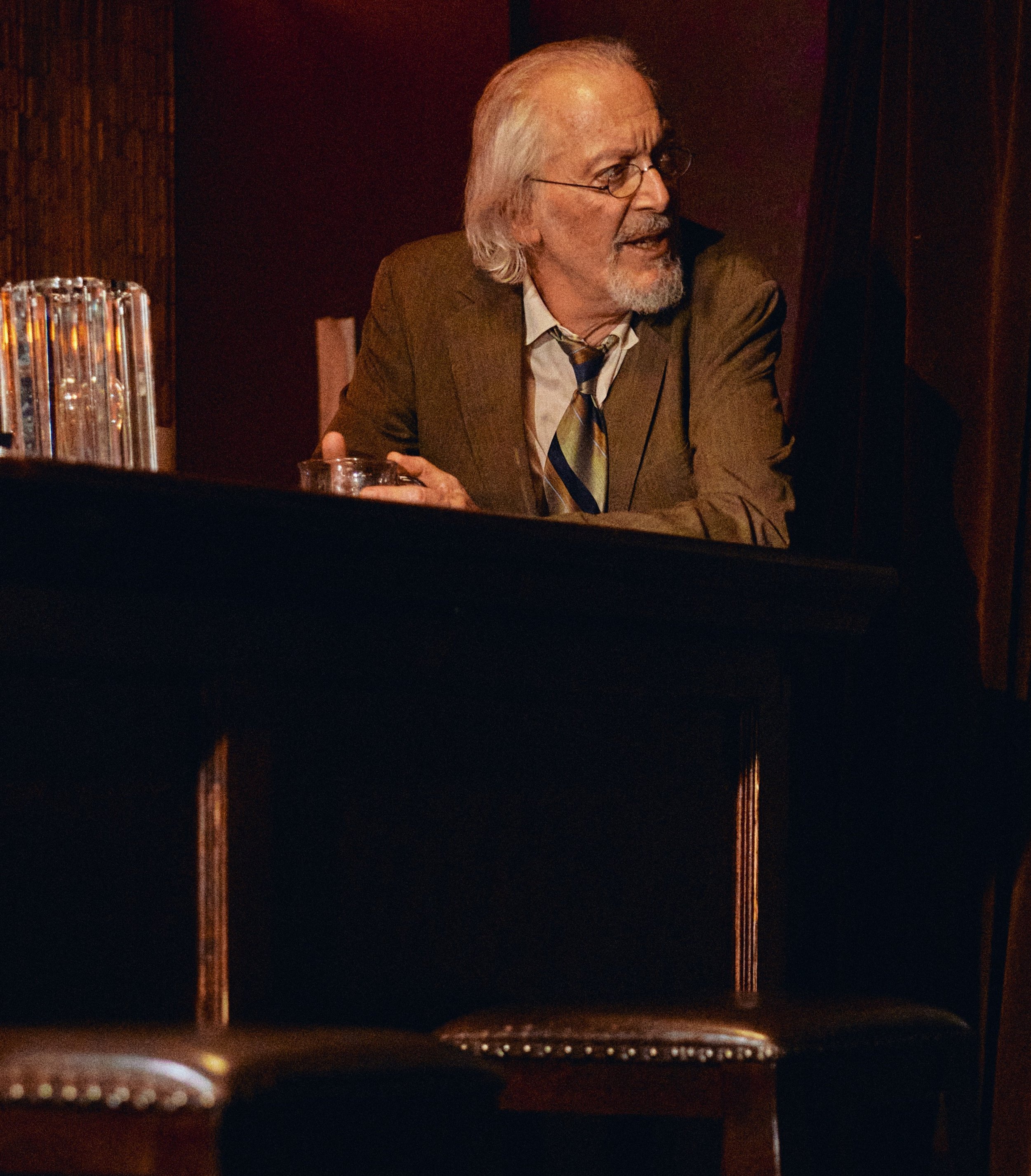

Ronald Guttman as Jean-Baptiste Clamence, a once exemplary lawyer who struggles with moral issues, in a stage adaptation of Albert Camus’ novel The Fall.

Amsterdam’s red-light district, circa 1956. A man walks into a bar and chews on the question: What does it mean to fall from grace? And, as a man who is having a few drinks in a bar and talking to strangers, he will ask many more questions, sometimes personal and often philosophical. In The Fall, by Albert Camus, a French philosopher who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1957 and is considered the father of existentialism, the man in the bar is Jean-Baptiste Clamence, a former Parisian lawyer who has himself fallen from grace.

Audience members become fellow bar patrons in Mexico City bar, where Clamence (Guttman) shares his story. Photographs by Zack DeZon.

At the heart of Alexis Lloyd’s stage adaptation of the terse philosophical novel, published in 1956, is veteran actor Ronald Guttman, who plays Clamence. In a faded mustard yellow suit that has seen better days, Guttman brings great elegance to the role with his tall stature, slim figure, and a mop of white shaggy hair that he pushes back with urgency from time to time. The actor’s unhurried delivery, punctuated by sudden outbursts, is like a slow boil—mostly calm but with small eruptions of desperation.

His “coup de grâce” has brought him to the Netherlands, a place “like a dream, a dream of gold and smoke. … It’s about the sea, the ocean, leading to Cipango, Java, and all these islands where men die crazy, but happy.” He finally declares, “Here we are at the heart of things.”

Under the direction of Didier Flamand, the Soho Playhouse theater is well utilized. The space features a postage stamp–sized stage, café tables and a bar. When Clamence moves back and forth between the bar and the stage, he creates an intimacy as we become not only audience members but fellow bar patrons. The bartender, who may or may not be an actor (no credit is given), plays his role calmly and effectively, and when Clamence heads to the back of the bar, at the farthest point from the audience, the quiet moments of drinking add pauses that help steady the pacing. Soft music, which alternates between violin and the tinkling of a synthesized piano, emerges as an undertone to the transitions.

“I was haunted by a ridiculous fear: that you shouldn’t die without having confessed all your lies.”

As we learn more about Clamence’s fall, the mood of the play shifts, and the genteel storyteller takes on a more manic urgency. In Camus’ work, others often become intolerable and social expectations feel like judgments. This happens to Clamence, whose descent begins with irritation with his own behavior and an overwhelming feeling of being judged by others. When he discovers that his drive to do good might not be completely honest, he begins to unravel. As a lawyer, he maintained an exemplary career of helping those less fortunate, especially widows and orphans. He thinks he’s a pretty awesome guy, but his fall from grace begins with a Freudian slip. One day, after helping a blind man across the street, the man thanked him, to which he replied: “Nobody would have done the same.” This slip of the tongue changes everything, and doubt begins to creep into every action, gesture, and interaction.

Albert Camus’ The Fall runs through Nov. 19 at the Huron Club at Soho Playhouse (15 Vandam St., Manhattan). Evening performances are Wednesday through Friday at 7:30 p.m. Tickets are available by visiting theater555.venuetix.com.