A Jewish Joke is a one-man show about partnerships, but that is just one of its several paradoxes. The play explores Jewish comedy, though from the serious viewpoint of its effect during the era of the Hollywood blacklist, when humor could either get a guy out of a jam, or reinforce anti-Semitic stereotypes. Many old jokes are told during the 90-minute production; however, they are delivered with such odd undertones that it is impossible to tell whether director David Ellenstein was hoping for legit laughter or uncomfortable sighs from the vintage zingers that are rife with sexism and prejudice. And Joke is a play about writing which, when it falters, does so because the script is, at times, contrived or repetitious. When it succeeds, it does so because Phil Johnson, of San Diego’s Roustabouts Theatre Company, so fully inhabits his role that his character’s stressed-out persona transcends the page.

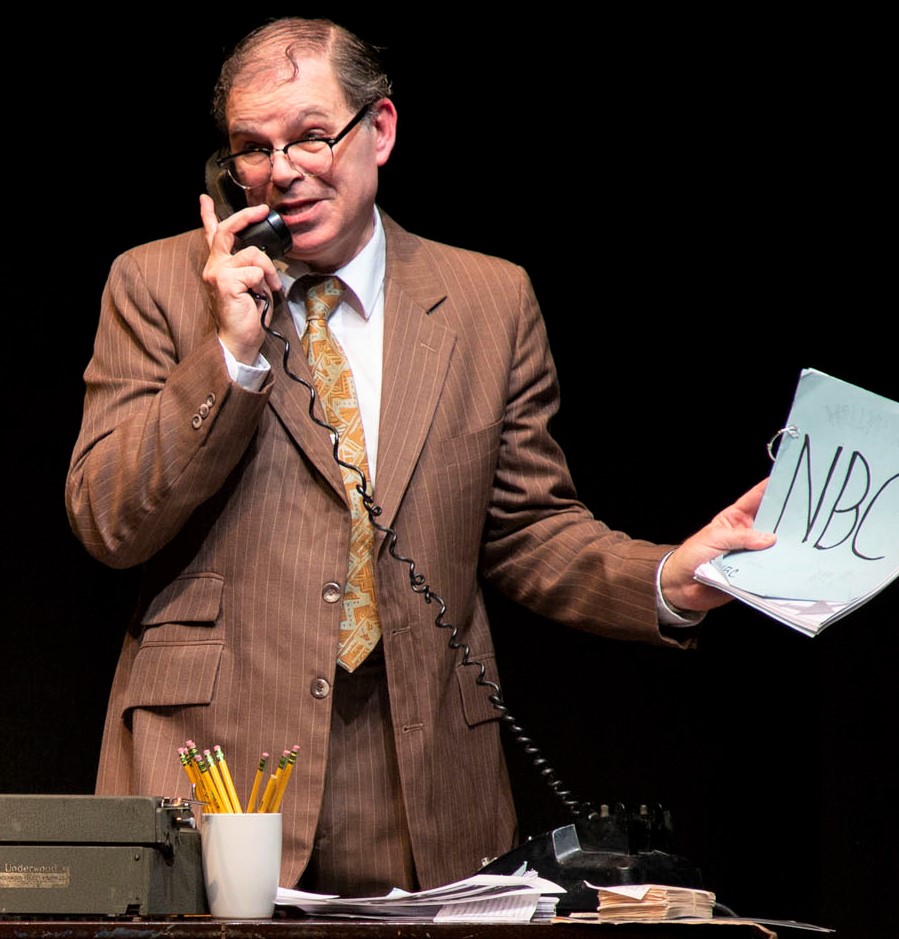

Phil Johnson as Bernie Lutz in A Jewish Joke, written by Johnson and Marni Freedman.

Johnson portrays Bernie Lutz, a film writer for MGM Studios in its mid-20th-century heyday. Though successful at his craft, he looks the worse for wear. His sad brown suit is wrinkled, his tie atrocious, his eyeglasses cheap, and his limp comb-over barely covers his scalp. He would be considered Kafkaesque, except that on this particular morning he finds he has been transformed into, not a cockroach, but a commie. His name, along with that of his lifelong friend and writing partner, Morris Frumsky, have turned up in Red Channels, the right-wing publication that, in 1950, accused scores of entertainers and journalists of having ties to the Communist Party (Real-life names cited by Red Channels ran the artistic gamut from Orson Welles to Dorothy Parker to Leonard Bernstein.).

It seems Morris had recently taken Bernie to a soirée that was more than just the cocktail-weenie extravaganza Bernie thought it to be. The fact that Morris is nowhere to be found as the play begins, despite the fact that their latest flick, The Big Casbah, is set to premiere that very evening, telegraphs all we need to know about Bernie’s impending doom. But Johnson, who co-wrote the piece with Marni Freedman, walks us through Bernie’s very bad day nonetheless. First, it turns out that the government had sent him a warning letter regarding the “important work of investigators under Senator Joseph McCarthy,” but he conveniently had torn it into three pieces without bothering to read it, allowing him to now build tension by slowly finding each section amid the piles of crumpled papers strewn about his bungalow. Then his colleagues begin disassociating. Danny Kaye shows him the door. Louis B. Mayer has no time for him. And when Harpo Marx gives him the silent treatment, he reaches a crisis point: testify against Morris to clear his own name, or protect his pal and risk sacrificing his career.

Bernie treads the fine line between comedy and tragedy. Photographs by Clay Anderson.

Without other characters in the room to play against, Bernie frequently turns to the audience and tells one of the many off-color gags he has collected on index cards. Most are groaners and, whether meant to be awful or not, they do keep the audience from becoming too emotionally caught up in Bernie’s dilemma. It’s the old “alienation effect,” a technique pioneered by another member of the Hollywood blacklist, Bertolt Brecht.

Bernie also has framed pictures of his wife and his parents with which to interact. But mostly, he is on the phone. Indeed, the plot revelations are entirely dependent on the seemingly endless number of calls that Bernie makes and receives. The playwrights employ a couple of devices to minimize the drudgery. Rather than repeatedly having to dial the rotary phone, Bernie has an unseen secretary place his calls. Somehow, she is able to do so with lightning speed, adding a surreal aspect to the evening. And Bernie answers the phone each time with a different one-liner (“Bernie’s Yacht Club”). None are particularly funny, but it beats enduring a hellacious string of hellos.

Production supervisor/designer Aaron Rumley provides a desk for Bernie to work behind, and I will just assume that its drawers are full. Why else install hooks across the front of it and glaringly hang from them the scripts that Bernie risks forfeiting? Regardless, Johnson, who has been touring and perfecting this role since 2016, when the show won Best Drama at the United Solo Fest NYC, makes it work, taking his character’s motto to heart: “When there is no mensch, be the mensch.”

A Jewish Joke, by Marni Freedman and Phil Johnson, runs through March 31 at The Lion Theater (410 W. 42nd St.). Evening performances are at 8 p.m. Wednesdays through Saturdays; matinees are at 3 p.m. Sundays. For tickets, call Telecharge at (212) 239-6200 or visit ajewishjoke.com.