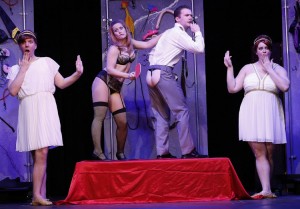

If you're wondering what to see at this year's Fringe Festival, you won’t go wrong if you head to Valerie Hager’s autobiographical, solo show, Naked in Alaska. It chronicles the joys, frustrations and heart break Hager experienced in her 10-year career as a stripper which took her from Tijuana all the way to Fairbanks, Alaska.

So it’s just another stripper confession story, chock full of cliches and stereotypes?

Hardly!

Over the last few years, the stripper memoir has become an American cultural phenomenon. Booty-shaking, pole-climbing, tell-alls, such as Diablo Cody’s Candy Girl, Ruth Fowler’s Girl, Undressed and Lacy Lane’s Confessions of a Stripper were runaway best-sellers which spawned numerous imitations. It’s a genre ridden with cliches and one of the most persistent (and annoying) is the female protagonist who comes from a educated, middle-class background and is the “last person you would ever expect to be stripping." (Cody says, “I had spent my entire life choking on normalcy, decency and Jif sandwiches…for me stripping was an unusual kind of escape.”)

Stripping may have been an escape for Hager, but it was hardly an escape from normalcy, decency or peanut butter sandwiches. Rather, hers was an escape from a harrowing adolescence. Describing her young, troubled self, Hager says “I was this young girl who was a secret bulimic for over a decade, who became a crystal meth addict and was expelled from high school.”

It’s that kind of unadorned honesty and humility that makes the show so compelling.

Early in the show, Hager and her impressive director Scott Wesley Slavin demolish the “Last Girl in the World" cliche and use the show’s multimedia format to great effect. The play opens with Hager shooting up crystal meth, while a montage of childhood photos rapidly flashes on a projection screen. It was an exciting and promising opening to a show which didn’t fail to deliver.

As it should have been, Venue #5 at the Lower East Side’s Theater of Whimsy was tightly packed with exuberant and slightly tipsy theater lovers. Throughout the evening, Hager’s energy, honesty and humor kept the crowd rollicking with laughter and applauding her seductive pole dancing. She has talent, guts, charisma, a taut petite frame and a treasure trove of distinct mannerisms, voices and impersonations. Over the course of the show, she plays a dozen characters, and plays them well. (Charlie, a stooped-back, foul-mouthed, African-American stripper, was a particular crowd favorite.)

“It’s a show dedicated to the outcast, the forgotten,” Hager says. “I wrote Naked in Alaska for any of us who have ever felt different and or on the fringe.” While the show may be dedicated to outcasts and other marginal figures, Hager’s search for something to belong to, her own “tribe,” is something that many, if not all us, can relate to.

So get down to the Theatre of Whimsy (aka the C.O.W.), grab a few drinks at the lobby bar, and catch Naked in Alaska before it moves on to Chicago’s Fringe Festival at the end of the month. Because as one audience member said after the show, “I am so glad I came. So glad.”