Steven Levenson’s fast-paced and hilarious play, Days of Rage, opens in October 1969. America is riven. The war in Vietnam has taken more than 30,000 American lives. Martin Luther King Jr. and Bobby Kennedy have been assassinated. Twenty thousand mostly young people turned out to protest the war in Vietnam at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and police are assigned to contain and control the crowd at all costs. Eight of the protesters, later known as the Chicago Eight, were put on trial in late August 1969. Word goes out to bus protesters to the trial. Both the protesters and the Chicago Eight see the case as a way to put the nation itself, its racism and unjust war, on trial. Levenson’s powerful play focuses a sharp gaze at politics and the hidden volatility that can tip over into violence and the spilling of blood.

“Levenson writes with great clarity about the fundamental unclarity of the human situation. Several times Jenny talks in startling detail about the effects of napalm and the Vietnamese children it has killed. It is the spring of her idealism and of her willingness to resort to violence. Hal has no satisfying response to her.”

The play, adventurously directed by Trip Cullman, opens with a crash of music and blaring lights that subside quickly, leaving the audience facing the interior of a house: a living room below and bedroom above. It is in this house that the intimate political and personal saga of “the collective” unfolds. Spence, Jenny and Quinn (Mike Fest, Lauren Patten, and Odessa Young, respectively) have quit school to join the movement and, with two more of their friends, created “the collective.” The loud period music of Darron West’s brilliant sound design punctuates the short scenes capturing the heady mix of weed, idealism, radical politics and youth that fills the house.

For those old enough to remember, the mix is pitch-perfect. These are days of free love, of radical politics, of revolution, and of rejecting parents, school, and, most passionately of all, the war in Vietnam. Spence has a volume of Lenin that he reads. As members of the collective, the three share all decisions (money) and responsibilities (dishes). Even their bodies are on a rotating schedule: “We share everything,” Spence explains to Peggy. “Why should our bodies be any different?"

The timing and ensemble work of the actors is flawless. Spence, Jenny and Quinn spend their days fruitlessly trying to sign people up for free rides to Chicago for the protest. The story takes off with two events. Hal (J. Alphonse Nicholson), whose brother is fighting in Vietnam, is a gentle black man who works for a living and whose quiet attention stirs Jenny into life and into a reevaluation of that life as a romance buds. How will Hal’s presence in Jenny’s life play out in a collective in which everything is shared?

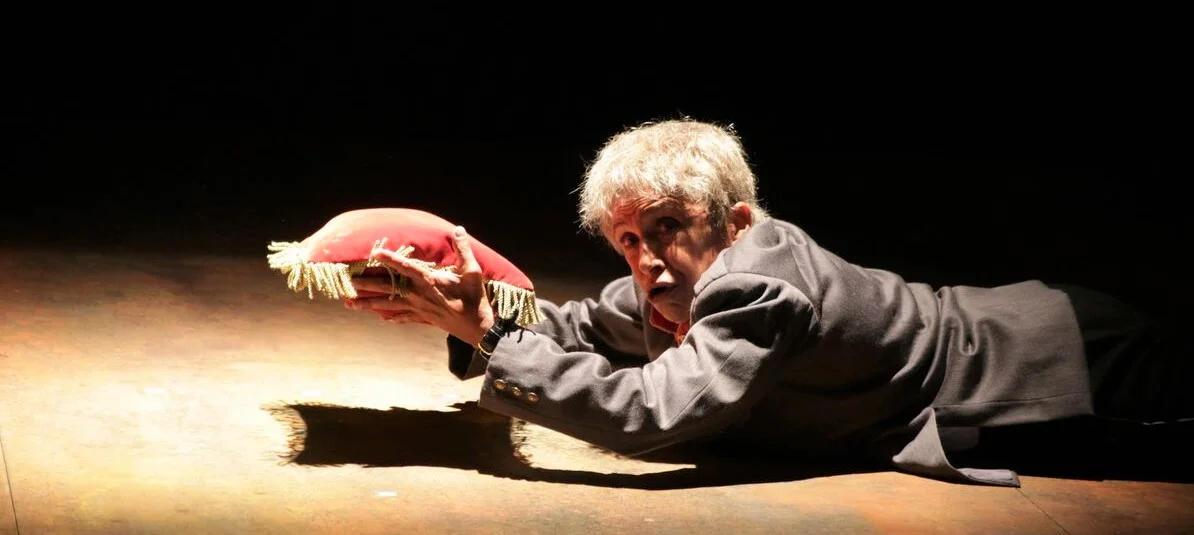

Lauren Patten (left) is Jenny and J. Alphonse Nicholson is Hal in Steve Levenson’s Days of Rage. Top: Tavi Gevinson (left) plays outsider Peggy, and Odessa Young is Quinn. Photographs by Joan Marcus.

At the same time, a wacky outsider, Peggy (Tavi Gevinson), desperate for a place to crash even with $2,000 in her pocket, swears allegiance to the Revolution and worms her way into the group. It is Peggy who first insists she is being followed by the FBI. It is Peggy who will try to get the collective to expel Jenny, and it is she who will supply Spence with a gun, egg him on to use it, and push the collective over the edge. This is the edge that Levenson sets out to explore, the cocktail that will or will not explode into violence.

Levenson writes with great clarity about the fundamental unclarity of the human situation. Several times Jenny talks in startling detail about the effects of napalm and the Vietnamese children it has killed. It is the spring of her idealism and of her willingness to resort to violence. Hal has no satisfying response to her. Are there times in which violence makes sense? But shattering news arrives: two friends have accidentally blown themselves up in an attempt to bomb a Detroit bank as an act of political protest. Hal points out that innocent workers in the bank, whose only “crime” is that they were trying to make a living, would have been killed if they had succeeded. It is now Jenny and her friends who are silent. Clearly, this violent protest cannot be the answer, either.

There is a second instance in which a bomb fails to explode—in a story Jenny shares with Hal. They are spooky moments, in which life appears to be imitating art since this play was already in previews when the country was startled by pipe bombs sent to prominent Democrats which have also not exploded. The year 1969 is a window into our fraught times, and Levenson uses it just as Arthur Miller used the Salem witch trials to focus his unsparing gaze on the McCarthy years in The Crucible.

Days of Rage is playing through Nov. 25 at the 2nd Stage (305 West 43rd St.). Evening performances are at 7 p.m. Tuesday–Thursday and at 8 p.m. Friday and Saturday; matinees are at 2 p.m. Wednesday and Saturday. Tickets from $40. For tickets and information, call (212) 246-4422 or visit 2st.com.